Merit and monetisation: A study of video game user-generated content policies

Abstract

This article explores the alternative system of contractual regulation that permits monetised user-generated content (UGC) in the video game industry. By situating the user in an industry where it is possible to earn millions from ‘playing games’, this article challenges the assumption in copyright doctrine that the user is a non-professional amateur, whose motivation for creating UGC is altruistic. The fundamental question in this article is about copyright incentives: who should reap the rewards for the creation of UGC? To answer this, the article examines the UGC policies of 30 popular game titles, revealing the distinct, but nuanced, concept of monetisation. The article illustrates how monetisation is constructed as a limited, merit-based allowance that both encourages and constrains the possibility of a user-led industry.Introduction

Making a living from playing games is no longer a childhood fantasy, but a lived reality for a privileged few internet influencers (Gandola, 2022). Indeed, for the newest generations, the playing and sharing of video game content is perhaps one of the most culturally important forms of entertainment, and undeniably, consumption of game content is an important part of life online. In 2021 alone, over 250 million game-related videos, and 90 million hours of livestreams, were uploaded to YouTube (Wyatt, 2021).

For copyright scholars, the very existence of this user industry is a puzzle; it is based on continuous collaborative creativity that is notoriously difficult to categorise under the author-user binary of user-generated content (UGC). Much of the value of this new digital entertainment is being offered by ‘users’ and their recreation, reinterpretation and extension of the game world: but it is almost certainly, and reductively, copyright infringement under a strict, doctrinal paradigm. Instead, this industry of user recreation is made possible, not because of enabling copyright laws, but in spite of a restrictive legal framework. Not only is heavy-handed copyright enforcement ill-advised in this industry, doing so would risk alienating influential user communities. Game creators speak more idealistically of “encouraging [UGC, which] leads to a creatively, and potentially commercially vibrant market” (Alae-Carew, 2020, p. 22).

This article illuminates how game creators are relying on contracts to cut through the gordian knot of default copyright law, creating a parallel system of regulating user creativity akin to a Creative Commons style of ‘some rights reserved’ licensing. The article uses an empirical study that systematises and categorises a selection of 30 video game UGC policies to show how game creators construct the nuanced concept of monetisation in juxtaposition to commercialisation. In doing so, the industry fashions an attempt to both reward and incentivise the otherwise unpaid marketing labours of UGC creators, while constraining the potential for a competitive blockbuster by a corporate entity.

The first section outlines the concept of UGC as it is understood in copyright discourse and employed in the video games industry. This Section illustrates a tension between how UGC is constructed in doctrinal law versus community practice, with contracts being used to tailor a parallel system of regulation in the industry. Section 3 offers a brief overview of the methods employed for the empirical study of UGC policies, with details of the data gathering and coding process. Sections 5 and 6 examine the constructed concepts of commerciality and monetisation, in turn. The article concludes that the parallel system of contractual regulation of UGC, while promising, does not remedy the fundamental conflict between the paradoxical creative ‘user’ who makes ‘content’, and the ‘authorial’ creator of a ‘work’.

User generated content in video games

The concept of UGC is not new per se, but the forms it takes are, by their nature, in a constant process of evolution. Part of the difficulty (and attraction) of studying UGC is that at its core it remains an “ideologically flexible" (Erickson, 2017) umbrella term to describe the collective modes for producing and distributing creative content, a process which has been accelerated with the advent of Web 2.0 technologies. Earlier more prescriptive approaches to defining UGC, like the OECD (2007), define the concept with specific criteria: that it is content which shows (i) creative efforts (ii) published on online platforms, (iii) by users outside of their professional practices and routines. More recent perspectives offer flexible interpretations of UGC, depending on the scale of independent creation, derivation from existing works, and collectivist and communicative efforts within a community (see e.g., Gervais, 2009; Iljadica, 2020).

The flexibility and adaptability of the UGC concept leads to new modes of expression for analysis, of which game content forms one vector. The most highly publicised form of making a living by ‘playing games’ has manifested in the form of gamer personalities (influencers) who live stream or pre-record edited gameplay videos (collectively referred to in this article as ‘game videos’), which are usually shared on online platforms such as YouTube or Twitch. A striking feature of this phenomena is the fact that it is possible to make a very lucrative living from this business model; examples of famously wealthy game personalities include PewDiePie, Markiplier or Jacksepticeye, who are followed by millions and make millions in return (Saab, 2021). Many of these personalities are not highly skilled players and nor are they esteemed critics; instead, most of the value they contribute is light-hearted entertainment, usually, but not exclusively, humorous in nature. At the other end of the ‘playing a game’ spectrum, the increasing profile of eSports (competitive video gaming) has seen the rise of the professional ‘eAthlete’, who trains and specialises in gameplay with the same level of intensity as a traditional sports athlete (and in some cases has surpassed traditional sports in popularity – see Thomas, 2020). Evidentially, where videos of game content are concerned, users are becoming increasingly professionalised in the form of a new digital entertainment industry, rather than a niche community.

Other types of game content include (but are certainly not limited to) game photography, modding (a slang term for modifications to the game, changing the way it looks or behaves), and other fan works, such as the creation of fan art. Often, these types of UGC prolong or extend the game universe in a dialogic fashion, by e.g., acting as post-release quality control (e.g. the extensive community modding of CD Projekt Red’s Cyberpunk 2077, detailed in Irwin, 2021), recontextualising the game as a competition (e.g. speed running) or contributing to the lore of the game world (see e.g., the quasi-fabled knight user-created character ‘Let Me Solo Her’ in Bandai Namco’s Elden Ring, detailed in Smith, 2022).

Having outlined the concept of UGC and its specific application to video games, it is apparent that the rise of derivative ‘user industries’ raise questions about both the value of the new content being created and who should be rewarded for these new modes of production and distribution: with the game creator, who provides the tool for its creation, or the user, who creates the successive content (see Lastowka, 2008)? Whereas copyright law, as the primary form of legal regulation for ownership of creative content, should in principle address this dilemma, instead, as this article will illustrate, the construction of UGC which has been developed in the video game community is a conduit through which we can examine flaws in the legal treatment of UGC.

The following subsections will consider two key components of the legal concept of UGC, as distilled from the definitions outlined above: UGC as creative content created by an amateur. In doing so, these sections will illustrate the tension between the existence of these new types of cultural products and their regulation under the existing copyright framework.

User generated content as ‘creative content’

While the ‘content’ component of UGC can in principle include multiple different types of creativity (see e.g., taxonomy forwarded by Gervais, 2009), most commonly it involves reusing existing copyrighted works owned by a third party. Certainly, this is the case for the variety of video game UGC outlined above.

The copyright content in question is usually owned by a game publisher or developer. Games are considered “complex subject-matter” as well as a stand-alone object of protection (see Case C-355/12 Nintendo Co Ltd v PC Box SRL [2014] OJ C93/8). As such, games cannot be reduced to a simple form of software, but rather may implicate several other different types of copyrightable subject-matter including: video (e.g., full-motion videos or cutscenes), graphic works (individual frames, character designs), audio (soundtracks, dialogue) and literary works (in-game lore, scripts). While many game companies will outsource aspects of this subject-matter’s creation to other third parties (e.g., developers, composers, voice actors), the usual contractual and employment relations revert ownership rights to the game publisher.

Importantly, the initial grant of ownership to the game publisher is resilient to outside intervention. Whereas the user may generate much of the value of UGC in offering their entertainment or skill, copyright law has a narrow view of their creative input and to date has not recognised an authorial interest that could act as a viable challenge to the rightsholder’s initial grant of ownership. While this matter has rarely been considered in the courts (in the US, see and Atari Games v Oman 888 F2d 878 and Midway Mfg v Artic International 704 F2d 1009; in the UK see Nova Productions Ltd v Mazooma Games Ltd & Ors [2007] EWCA Civ 219) the legal treatment to date has been to designate the game creator (or more specifically, the software developers employed by that company) as the entity which make the user’s creative input possible, by creating the game in the first instance. In a cyclical fashion, even if a user is technically the entity pressing the button and changing the audio-visual outputs on a screen, courts do not usually ascribe them an authorial interest in those outputs, because that interaction was already preconceived by the game developer within the pre-set rules of the software. While the user has the illusion of agency, this is ultimately constrained (forming part of a larger ontological debate in game studies on narratological and ludological perspectives of game design – see overview in Lastowka, 2013). In the words of the UK court in Nova Productions Ltd v Mazooma Games Ltd, the user does not demonstrate the “artistic” kinds of creativity associated with a claim to authorship. Rather, “all [they have] done is to play the game” (para 106).

To the extent we find such precedent persuasive (noting that such a matter has not come before the CJEU to date), the audio-visual outputs of a game that appear on the screen, even if caused by the user, will nonetheless revert to ownership by the game company as the entity providing the tool for its creation. It is precisely for these reasons that game UGC is conceptualised differently from a creative work made by an author, in copyright discourse. This distinction has been rightly critiqued (to name but a few, Gibson, 2006; Craig, 2011; Meese, 2018; Iljadica, 2020) for its inconsistent treatment between what are both prima facie, precisely the same types of creators that copyright seeks to identify.

Instead, where the user has no authorial claim over their UGC, they are left with the option of seeking to benefit from a copyright exception to escape liability for copyright infringement of game content. However, the EU copyright regime gives little solace to the user looking to exploit their UGC. Consider a common example of game UGC: if a user wants to create a game video where they play the entirety of a game from start to finish on their Twitch channel (a ‘playthrough’), this will run afoul of several issues that would prevent the straightforward application of a copyright exception.

First, using even quantitatively small amounts of copyrighted works can be considered qualitatively substantial, thus triggering infringement (see Case C-5/08 Infopaq International A/S v Danske Dagblades Forening). Nonetheless, a playthrough which includes the entirety of the playable content of a game will be considered substantial as comprising the whole of a work, thus prima facie triggering copyright infringement in lieu of an applicable copyright exception. Modern games can take up to 200 hours to complete in their entirety, if they follow a linear narrative; games of infinite replayability or ones without a linear narrative make thousands of gameplay hours possible (e.g., multiplayer online titles, such as World of Warcraft).

Second, when creating a playthrough of a game, there are no straightforward applications of any of the specific situations envisioned by the closed list of InfoSoc Directive, Art 5. In theory, these exceptions provide legislative ‘carve-outs’ which permit the use of protected works in circumstances where that use can have social, political or economic benefits. While there are some likely exceptions that could apply to a playthrough, these quickly lose their viability once the purpose of a playthrough, as a limiting factor to many copyright exceptions, is interrogated. Usually, the purpose of playing a game, from the perspective of the UGC creator, is not limited by circumstance, but rather as a conduit for their own personality. This may be from their skills, observations, or rapport with their community. For example, a viewer may watch a famous speedrunner (who tries to complete the game in shortest amount of time possible, sometimes undermining anticipated finishing times by hours if not days) because of their talent in subverting the game system; another may choose to watch a game influencer or personality due to their relationship with the audience rather than their skill in a game, or indeed, may be amused at their (inept) approach to certain genres (e.g., reacting to jump-scares in horror games). In brief, the purpose of a playthrough and the value derived from it Is largely based on the interaction a user has with the player themselves, rather than the game per se.

Resultantly, while there are game videos which are, for example, dedicated to reviewing a game’s various merits or demerits, most playthroughs are not wholly, or even substantially, limited to this critique. A player may make a passing comment about a game’s functionality, appearance or broader social implications. But the purpose of their engagement with the playthrough is not targeted at “illustrating an assertion, of defending an opinion or of allowing an intellectual comparison between that work and the assertions of that user” (see Case C-516/17 Spiegel Online v Beck, para 71), such that they could evoke the Art 5(3)(d) exception for uses for the purposes of criticism and review. Rather, this forms part of the broader conversation the UGC creator has with their audience. Likewise, while some game videos are clearly targeted parodies, most playthroughs will only contain moments of humour or mockery, which may or may not revolve around the context of the game. The current criteria for assessing parodies under the Art 5(3)(k), is outlined in Case C-201/13 Deckmyn v Vandersteen), which dually requires “first, to evoke an existing work while being noticeably different from it, and, secondly, to constitute an expression of humour or mockery” (para 20). Simply playing a game, and accompanying this with a video containing occasional humorous remarks, which may or may not be about the context of a game, will not satisfy the level of engagement (with the purpose of evoking and constituting) with the original work as obliged by this test.

Finally, the recent Copyright in the Digital Single Market (CDSM) Directive offered the opportunity for more substantive discussions and legislative reform of the legal treatment of UGC, broadly conceived (see Erickson, 2014; Furgal, Kretschmer & Thomas, 2020), and indeed resulted in the newly incorporated concept of “subject-matter uploaded by users” (Article 17(7)) (read: UGC). Lamentably however, the Directive does not offer any clarification or progression as to the legal treatment of UGC, but instead re-affirms the more traditional doctrinal standpoint that UGC is a concept which lies somewhere between the work of an author (who can authorise the use of such works per Article 17(1)) or the beneficiary of either of the exceptions outlined above (a limitation which is articulated in Article 17(7)). Neither of these safeguarding options provides solace for the creator of a playthrough who does not own the work they are playing, nor engages with it for a specific purpose other than as a conduit for their personality.

In summary, with no obvious candidate for a viable exception, and amidst the growing liability for primary infringement of the communication to the public right via streaming (Case C-527/15 Stichting Brein v Wullems t/a Filmspeler), the result is that it is not only legally precarious to create UGC, but also to consume it.

User generated content produced by an ‘amateur’

The ‘amateur’ component of UGC is taken quite literally at its definition to suggest that the user is making content for the love of the original work; commercial activities or profit-making (i.e., per the OECD definition of creative efforts which take place outwith professional practices) will generally preclude a cultural product from being defined as UGC. While only obliged in limited circumstances under the InfoSoc Directive, Article 5, national implementations often extend the non-commercial factor into their assessment of ‘fairness’ (see e.g., fair dealing factors in the UK). As such, even if a circumstantial copyright exception is applicable, it is in any case likely to be defeated by the commercial and profit-making nature of many types of UGC (noting however, that Case C-406/10 SAS Institute Inc. v World Programming Ltd. may offer an alternative solution for commercial uses in the execution of mandatory exceptions). It is now commonplace that, e.g., a streamer can receive ad revenue through partnership programmes, sponsorships or fan donations in conjunction with their streaming activity. While there is no static definition of commerciality in EU copyright jurisprudence, the definition given by Creative Commons indicates that this could be “any manner that is primarily intended for or directed toward commercial advantage or private monetary compensation” (Creative Commons Corporation, 2009, p. 11). Similar formulations are evident in factorial assessments of potential market harm in US fair use defences (see 17 U.S.C. § 107), and the more explicit ‘non-commercial user-generated content’ exception encoded in the Canadian Copyright Act (see s29.21). With this strong non-commercial formulation, the hallmark of UGC and what differentiates it from the authorial ‘work’ is that UGC cannot be used to divert profits from the primary rightsholder (profits in themselves thus become suspect) or be used in the course of a business. Both concepts can work in tandem, synonymously, such that the recompense to e.g., streamers of UGC, would almost certainly fall within the ambit of a commercial activity.

Thus, in copyright doctrine, the user is defined as an amateur who creates content for the (altruistic) love of an existing work rather than any financial recompense. This construction is directly challenged by the new forms of UGC we see in the video game industry, which has become highly professionalised. The paradoxical result is that the user is a creator, but not the ‘right’ kind of creator that is awarded an exclusive right (an author); and while they exist in a space where exceptions are possible in theory, they are rarely available in reality.

Contract: an alternative regulatory mechanism

With the slow pace of policy change and judicial interpretation by courts, it seems unlikely that the legal treatment of game UGC in copyright doctrine will change any time soon. Without intervention, this leaves UGC creators in an uneasy state where their infringement is tolerated, with the omnipresent threat of enforcement measures which, in some cases, could disrupt access to income routes that support their livelihood. In the face of this doctrinal gordian knot, the video games industry has responded with an alternative mechanism for regulating user creativity: contract. Now, rightsholders routinely consider the user who approaches a game, not as a passive consumer, but as someone with the potential to be an active creator, who is interested in what rights are licensed to them to interactively create with game content.

End User Licencing Agreements (EULA) have long accompanied games at the point of sale and continue to be the primary contractual document which set the terms of use between a game creator and user. In recent years, similar forms of licensing agreements have formed determinative components of CJEU judgements on the concept of digital exhaustion (of software, see Case C-128/11 UsedSoft GmbH v Oracle International Corp, and of eBooks, see Case C-263/18 Nederlands Uitgeversverbondv Tom Kabinet). While not litigated in the context of video games specifically, these cases provide context for the broader, policy-oriented question as to what degree a rightsholder should retain ongoing control over digital works post-sale, and how persuasive the terms of a contract can be when determining this. Creative interactions with works, of the kinds envisaged by the video game UGC outlined in this article, necessarily form a component of this broader question of post-sale use of game content.

UGC policies themselves (as distinct from the EULA) are relatively new, and remain an understudied contractual object, with some intermittent scholarly work in the US (Marcus, 2008; Ahuja, 2017) and the EU (Mezei & Harkai, 2022). UGC policies are often supplementary to the primary EULA, and may be embedded in lengthy terms and conditions or codes of conduct. Much like the Creative Commons style of ‘some rights reserved’ licensing, game companies are increasingly using UGC policies (in part) as opt-out mechanisms for the automatic protection bestowed by copyright in respect of their users’ UGC. Copyright is still centrally important to this concept because it grants the game owner the initial right to exploit and determine those terms under which the UGC may be exploited, but the subsequent system of sanctioned creativity bears little resemblance to the doctrinal regime that enables it. This divergence from the law appears to be both an effort to encourage influential user bases to create and distribute UGC, which may have a promotional effect for the primary game product, while also offering a more proximate degree of control over the quality of that content than the default copyright regime specifies. Thus, in this study, unlike much of the broader literature on video game user contracts that (importantly) explore the tendency towards oppressiveness in contract (to name but a few, see Dibbell, 2006; Marcus, 2008; Lastowka, 2012; Harbinja, 2014), contract is positioned as a more neutral device that can both enable and constrain the possibilities for UGC. In doing so, the analysis that follows offers a conduit through which community-based regulations of UGC can reveal limitations of the current legal treatment of UGC in copyright doctrine.

Method

The primary aim of this article is to understand how UGC is conceptualised in the video games industry as constructed through a parallel system of contract, particularly in relation to the contradictory legal facets of the user as an amateur. To understand how UGC is constructed, the article employs an empirical method, surveying a range of UGC policies.

Dataset

The dataset for this study comprises 30 individual game titles, corresponding to 30 distinct UGC policies from 30 different game publishers. Game and eSports titles were selected based on their popularity and used in this article as a proxy for representative industry contracting standards, which were derived from crowdsourced ranking websites Ranker (ranker.com) and eSports Earnings (esportsearnings.com).

The most up-to-date versions of game EULAs, terms and conditions, UGC policies and other variants thereof (collectively, the ‘UGC policy’) were collected and viewed holistically as the package of documentation presented to a user, who would then make a determination about UGC authorisations. Resultantly, despite capturing 30 individual game titles, the study considers 61 individual documents which regulate the creation and authorisation of UGC, making for an average of 2 documents per title. Given that UGC policies are subject to change, static versions of these documents were captured on 21 December 2021 for the purposes of analysis, and are on file with the author. A list of the game titles and UGC policies examined is available in the Appendix.

Coding

UGC policies were coded according to two factors: which discrete activities were considered in relation to UGC, and; whether these were permitted (with or without conditions) or prohibited. This resulted in eight different types of UGC activities which were determined iteratively with reference to their salience and delineation in the UGC policies:

- Video: Creation of a moving image of a game, including live streams and pre-recorded videos.

- Monetisation: Permission to earn money (or equivalent) from videos uploaded to online platforms.

- Screenshots and game photography: Creation of a singular still, image, frame or screenshot of the game.

- Soundtrack: Use of a custom-made soundtrack that accompanies a game, otherwise known as an ‘original soundtrack’ (OST). This category specifically excludes licensed music from third parties.

- Fan works: Creation of any derivative content based on a game or including game content (such as characters). This includes fan fiction, fan art, fan sites and fan games.

- Merchandise: The creation and sale of products based on a game, such as clothing featuring the image of a game character.

- Mods: The creation of modifications to the code of a game that changes the way it looks or behaves.

- Commercial use: Any use of a game in commerce (i.e., the course of a business).

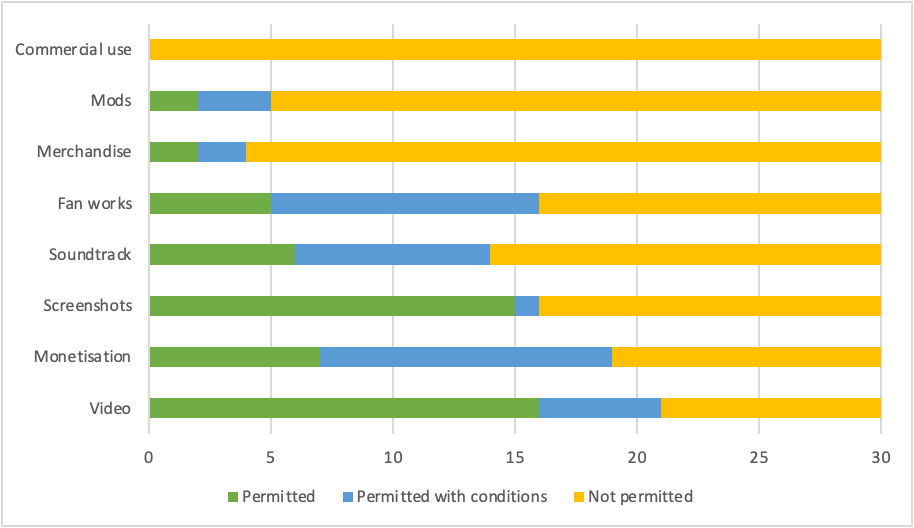

Table 1 illustrates how permissions are granted in relation to each UGC activity.

|

UGC type |

Permitted |

Permitted with conditions |

Not permitted |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Video |

16 |

5 |

9 |

|

Monetisation |

7 |

12 |

11 |

|

Screenshots |

15 |

1 |

14 |

|

Soundtrack |

6 |

8 |

16 |

|

Fan works |

5 |

11 |

14 |

|

Merchandise |

2 |

2 |

26 |

|

Mods |

2 |

3 |

25 |

|

Commercial use |

0 |

0 |

30 |

The following sections explore in more detail how, through the prism of contract, game creators regulate user behaviours through the new construction of monetisation as distinct from commercialisation, and why this is significant to understanding the community regulation of UGC in this industry. In doing so, the analysis unbundles the the concept of ‘profit-making’ from the broader construction of the ‘commerciality’ of UGC embedded in copyright doctrine.

Defining ‘commercialisation’

Commercial activities with UGC are universally prohibited by game creators (30/30). In essence, the possibility of commerciality is considered as a distinct activity in the UGC policy if only to highlight it as an emphatically prohibited activity. Commerciality is constructed in the UGC policy to restrict use of a game where the user works as, or for, a corporate entity, or in a manner that is in competition with the primary product of the corporate entity developing or selling the game. This is a narrower construction than the meaning ascribed to commerciality in copyright, which feasibly includes such activities, but is not exclusive to them.

‘Where the user works as, or for, a corporate entity’

While copyright doctrine does not oblige that a user must be a natural person, and can plausibly be a corporate institution, UGC policies emphatically construct the user as an individual and natural person who is unaffiliated with any corporate entity. The user is given a distinctly personal right to create UGC for “enjoyment” (CD Projekt) and “entertainment purposes” (Cygames). “Play” is in fact a common condition of the UGC policy (see Bethesda and Wizards of the Coast) despite there being no comparative legal concept. Others more explicitly exclude corporate entities as beneficiaries of the UGC policy. Riot Games, for example, specifically prohibits UGC projects when they have been in any part crowdsourced, or involve a business. Microsoft, likewise, offers the possibility of a “commercial licence” which precludes the use of the generic UGC policy for commercial purposes.

While commerciality is not defined explicitly within the text of the UGC policy, non-commercial activities are described as something one makes for “themselves”, with a suggestion that commercial use might include “charg[ing] to cover your costs” or “constructed promotions” (Mojang). Curiously, eSports seem to be considered a de facto commercial activity outwith the scope of UGC, based on the assumption that any eSport creation will take place in a professionalised (e.g., ticketed, sponsored) setting. Mostly, eSports are excluded from the UGC policy by omission, while a minority specifically remove them from their ambit (Hi-Rez, Blizzard and Bethesda).

In sum, the UGC creator is ascribed homo ludens: a human engaging in (re)creation with a game for fun or frivolity, but not with the ‘seriousness’ or profit-making intention of business. This strong conceptualisation of the homo ludens within the UGC policy gives a targeted vision of the ‘user’, which is narrower in focus than the broader variant in copyright (where the user could feasibly be a corporate competitor).

‘A manner that is in competition with the primary product’

The construction of commerciality also has a protectionist dimension when the game creator’s commerce is concerned. Undermining the primary game market of the creator, or association with the game brand or assets, is likewise widely prohibited in UGC policies.

This restriction is most explicit in the context of merchandise, which is almost universally prohibited by game creators (26/30). Of the two companies that do permit merchandise, heavy conditions are attached, which are among some of the most lengthy and complex in this dataset. Mojang, creators of Minecraft, set specific limits on the amount one can earn from merchandise (i.e., no more than 5,000 USD in one calendar year), the types of merchandise that can be made (i.e., no more than 20 of one type of item) and specifications that any merchandise must be hand crafted (i.e. not industrially produced) (Mojang). Toby Fox similarly permits “most handmade items”, but not including apparel, merchandise sold on online stores or anything that can “compete with official merchandise” (Fox). Seven of the UGC policies include a wholesale obligation to include disclaimers about the UGC’s association or endorsement by the corporate entity as a brand (Epic Games, Riot Games, Blizzard, Microsoft, Wizards of the Coast, CD Projekt Red, Mojang). In sum, the treatment of restrictions on merchandising in relation to the corporate image of the game suggests UGC will be more heavily restricted when there is a risk of blurring or tarnishing the brand’s primary product, particularly with static, tangible game assets.

Like merchandise, screenshots are also puzzlingly restricted in UGC policies as compared to streaming a video; game companies are divided, almost in half, on whether screenshots and game photography are permissible (14 permitted without condition, 1 with conditions, and 14 prohibited). While it would seem that, in substance, the difference in value between a video and a screenshot would not be much (both in principle being graphical ‘frames’, or a series thereof), there is clearly a difference in perception as to what the game creator finds tolerable. Like the value of a brand in merchandise, there is more value in a static, still image of a video game object or character which may bear closer resemblance to the symbolic value of a brand, rather than the more ephemeral and unpredictable stream or video that embeds the user’s interactivity. It is, put simply, the symbolic difference between creating a video of a playthrough of a game from Nintendo’s Mario universe, versus creating an artwork of the same, highly recognisable, branded Mario character when removed from the game world.

The form these branded assets take is also important; fan works, for example, are a very diversified category of permissiveness (5 permitted without condition, 11 with condition and 14 prohibited). Within this broadly conceived category there is a difference in treatment between fan art and fan fiction, which is typically encouraged, versus fan games that incorporate assets into the game of a viable competitor (see, e.g., restrictions detailed by Riot Games, Wizards of the Coast and CD Projekt Red). Thus, to again take the example of Mario, there is a difference in perception as to the threat a UGC creator poses by writing a story about the Mario-verse characters in a new setting, versus using the famous 1-up mushroom graphics in a homage game, as a viable competitor in the primary market.

In examining the conditions surrounding the ‘do not compete’ mirror image of commerciality, it becomes apparent that many of the activities prohibited by game companies can usually (but not always) be associated with the protection of brand assets, and by extension protection by trade mark, rather than copyright per se. It is likely that the activities examined here are intended as interplay, such that a user cannot take a screenshot of a character, apply it to a t-shirt and sell it at a convention. Branding of the corporate entity is an omnipresent concern in UGC policies that often dictates its restrictiveness, particularly when individual assets can be divorced from the context of the game world and used in unsanctioned conditions outwith it.

Defining ‘monetisation’

Whilst the UGC creator is explicitly framed as a non-commercial, non-competitor, a surprisingly high number of game companies, if not the majority, allow for the monetisation of game content (7 without condition, 12 with). In principle, game creators offer users the possibility of deriving income from the content they create in certain circumstances. This contrasts with the broader restrictions in copyright, which tend to conflate money-making activities as ‘commerciality’ or ‘profit’. Importantly, ‘monetisation’ is construed very narrowly in the UGC policy, and should not be understood as the universal permission to make money from any source. Rather, when monetisation is permitted in the UGC policies, this concept refers to a user’s capacity to earn passive, merit-based income for limited types of content.

‘Merit-based income’

Many game creators explicitly describe the routes through which a user can monetise their UGC: through passive ad revenue, money gained from partnership programmes with online platforms (e.g., Twitch Affiliate Programme, YouTube Partner Programme, Facebook Level Up Programme) and fan donations (e.g., through the award of Twitch Bits – effectively mini-donations in the form of virtual currency from viewers of a stream). Much like copyright, the quantity of how much of a game can be used in monetised video footage is not relevant in the UGC policies; in theory there is no time limit as to how much video footage one can show. There is thus a trend towards granting wholesale permission to the user (and sometimes even deterrents from contacting the game company to confirm the same – see Red Barrels) to monetise content, rather than encouraging an ongoing, continuous assessment by the rightsholder.

The concept of ‘merit’ in monetisation is twofold: first that the quality of the content itself is of a standard which merits the grant of permitted UGC; and second, that income earned through monetisation is an indirect acknowledgement of that merit.

First, the qualities which trigger the merit-based grant of monetisable UGC include satisfying obligations for UGC to be creative. This might be by including “your creative input and commentary” (Nintendo), “your own unique content” (Mojang), “your own original contribution to the community” (Riot Games) or “your creative spin on our owned content” (Ubisoft). The natural corollary of obliging creativity is hostility to light-touch adaptations of existing works: UGC should not “just rip off or add light commentary to existing content [or] cannibalise the content of others” (Riot Games). UGC should “[h]elp foster community and creative expression. Simply duplicating content does neither. You’re better than that” (Ubisoft). The ‘original’ and ‘creative’ user is therefore presented in the UGC policy as deserving of more merit (‘better’) than those who merely ‘copy’ the work of other users.

For copyright scholars, the vocabulary surrounding these merit-based requirements provoke a fundamental paradox in terms of conceptualising the entity that is being described by UGC policy. ‘Originality’ and authorship are often conflated in copyright doctrine. Satisfying the standard of originality is a prerequisite of authorship, and thus first ownership of a creative work. In the EU, this standard of originality is satisfied when an author demonstrates their own ‘intellectual creation’ (appearing for the first time in Directive 91/250/EEC of 14 May 1991 on the legal protection of computer programs), which can be interpreted as demonstrating the authors’ free and creative choices, and their personal stamp (see e.g., Eva-Maria Painer v Standard VerlagsGmbH). These concepts echo the same requirements in the UGC policy which are instead framed as permission for the user to create; authorship and originality are apparently two distinct concepts where UGC is concerned, and one element can be obliged without the other being present. Riot Games for example, demand “original” content from UGC creators, but refuse to acknowledge “works of authorship based on the game” (Riot Games). It is unclear if the invocation of ‘authorship’ in the UGC policy is a deliberate engagement with the technical specificity of the copyright concept, or if it is intended to be interpreted differently. Either way, this contradictory nature is not acknowledged in UGC policy when it is possible that one can be a user who is both an original creator, but is not the author of a work. As Gervais (2009, p. 843) suggests, this pragmatism reveals an existentialist viewpoint of UGC: “it exists [only] because we say it does”.

Second, merit-based also refers to the method of attaining income, which is best described as an indirect acknowledgement of the user’s creative labours. Paywalls in any form (e.g., Patreon), while strictly constituting this definition of ‘monetisation’, are almost universally prohibited among rightsholders who attach conditions to the monetisation permission (with the exception of Mojang, who allow for a 24-hour embargo of paywalled content). As such, it may be more accurate to define monetisation as a user’s entitlement to derive passive income from their UGC, but not the active solicitation of money from other users at the point of access. In this sense, monetisation of UGC is not transactional, but rather merit-based; other users may reward the creator of UGC with their time, subscription or donation, but cannot be actively charged to access the content (evoking the hierarchy of users envisaged by Chapdelaine, 2017).

Further, as permission to monetise content does not extend to corporate entities, there is a more nuanced consideration of the source of profit as an important vector in determining the legality of UGC. Unlike copyright, which does not in principle distinguish between the natural and institutional user, all use is not equal under UGC policy. The analysis instead suggests that products of interactive works, where a user can add their own meaning through the process of play (e.g., a stream), versus repackaging aspects of the brand and selling these outwith the game world (e.g., merchandise), carry different levels of risk for the rightsholder. Unlike a third-party company, which would be prevented from using a video game character in an advertisement to promote their products or services, a user as a natural person can stream the whole of a game and earn (in theory) infinite passive ad revenue from it without this being considered a commercial activity: it is monetisation earned in respect of the user’s merit, which is in turn dictated by the value of its use for other users. It seems that for the latter, there is no perceived conflict with the sale of a primary product or substitution effect for experienced play versus observation, but for the former – the static asset – there is both a threat to the brand, as well as potential routes for future markets, justifying its restriction.

‘Limited types of content’

Monetisation is not a universal right of the user, but instead applies more narrowly to certain forms of content. Returning again to the more disparate category of fan works, many UGC policies differentiate, e.g., between fan art, which can on occasion be commissioned as a route for monetisation, and fan fiction, which is an explicitly non-income oriented activity (see Blizzard, Toby Fox). Interestingly, many of these restrictions parallel fan community norms around e.g., the selling or commissioning of fan art, but not fan fiction (Fiesler, 2018).

Instead, at its most narrowly defined, monetisation relates to the user’s ability to derive income from streamed and pre-recorded video content, which is permitted by the majority of rightsholders in the dataset (16/30). This is perhaps unsurprising as the creation of streams and pre-recorded game videos continues to dominate the game UGC spectrum. Of the nine UGC policies that do not permit the use of any kind of video content, eight form part of a broader all-rights-reserved model for companies which do not permit any kind of UGC (those being: Tencent, Activision, Wargaming, Cygames, Sony, Warner Bros, Bandai Namco and Konami). For the most part then, within these particular UGC policies, monetisation of video content is not a specific target to be prohibited, but rather forms part of the bigger context of an all-rights-reserved culture within specific game companies.

Conditions, when attached to monetisation of video content, often interplay broadly with non-copyright related areas concerning the quality and nature of the content itself. This includes prohibitions that protect the commercial viability of a game and its longevity, such as the prohibition of making videos that include spoilers or pre-release footage (Rockstar Games). However, many more are concerned with ensuring the ‘spirit and tone’ (Epic Games) of a game is preserved in any UGC videos. This may be achieved by preventing content which is “obscene, sexually explicit, defamatory, offensive, objectionable, or harmful to others” (Epic Games), or ‘objectionable’ for any other reason (Ubisoft). These conditions leave open the possibility for the game creator to determine what factors match the ‘spirit and tone’ of a game and the quality of its use. At its most broadly conceived, the allowance of monetisation is instead a revocable promise made by the rightsholder, which can be withdrawn for a multitude of broadly conceived reasons.

Limitations on monetisation also frequently distinguish between the audio and visual components of games, despite frequently being bundled together; while 21 game companies allow videos, only 14 allow use of the soundtrack that accompanies the game. The OST thus appears to have a different value, almost sui generis, severable from the rest of a game, which cannot be explained solely by the fact it is created and owned by third party music creators. Often, once conditions are applied to the use of the soundtrack, the use of the OST becomes very limited indeed. Monetisation may be wholesale prohibited for audio components (see CD Projekt Red and Toby Fox/Materia Music Publishing) or be used for “personal use and creative exploration” (Blizzard), which would seemingly exclude the possibility of including it in a game video on an online platform where the lines between the personal and public are blurred. A more common condition is that the OST cannot be used when divorced from the context of a game; it cannot, for example, be used to accompany a product review (CD Projekt Red). Thus, when OST use is permitted, it must be associated with the primary video game product; such a restriction is more analogous to the themes of restrictiveness in relation to branding and commercial conceptualisations of UGC for assets that can be used outwith the game world.

The conditions surrounding the form of content which can be monetised may also explain the curious absence of mods in this study (with 25 UGC policies wholesale prohibiting them), despite being both a theoretically interesting and, quite famously, widely tolerated community within the games industry (see Deng & Li, 2021). Previous attempts to monetise mods (see most recently, Bethesda’s Creation Club have failed precisely because of the attempt to monetise them. Instead, when mods have been successfully commercialised, they have tended to be subsumed within the authenticating rightsholder through a buy-out of the resulting modified game (see for example Dota, subsequently acquired by Blizzard, and Counter-Strike, a modified version of Half-Life subsequently bought by Valve). The solution in the UGC policy therefore seems to be to leave mods, as a contentious form of content in the community, untouched (that is, reserved by the rightsholder), with the possibility that reuse could become formalised at some other time through a separate licensing system.

Conclusion

In distinguishing between the concepts of commerciality and monetisation, this study offers a provocation to the classic puzzle of copyright in the digital era, namely the question of whether and how to award the continuous, often collective, creation of UGC. Recently, conversations around UGC and copyright have been fixated on the wholesale blocking and removal of content (particularly in the context of e.g. Article 17 of the CDSM Directive – see e.g., Frosio, 2020; Quintais et al., 2019). This remains a crucial discussion. However, the findings from this study suggest that another, less visible, frontier of discussion is not whether UGC is permitted or available – at least in this context, this is quite often the case – but rather, whether a user is permitted to be remunerated for their creativity. Indeed, this forms an important policy question about copyright incentives. Arguably, UGC policies approach the question of monetary rewards in a more structured way than copyright doctrine: ‘commerciality’ does not necessarily include, nor is limited to the concept of user profit or remuneration. Instead, there is growing recognition that the value of UGC can be recognised through passive monetisation of content, and that this is not in conflict with the rightsholder’s own entitlement for recompense via sales of (or within) the primary game product.

Of course, copyright is, according to some theoretical paradigms, intended to incentivise precisely the type of creativity outlined in this article; but it seems that UGC in the context of the game industry is thriving in spite of copyright, rather than because of it. In fact, the initial grant of copyright is only useful here insofar as it allows game rightsholders the discretion to forsake some of those rights to UGC creators through contract, which in turn reconfigures some economic rewards in favour of the ‘user’. As outlined in this article, earning income from the substantive use of the moving image of a game is, ironically, by far the most unproblematic UGC activity, despite posing a classic problem for the copyright regime. By contrast, there is more value, and thus less permissiveness, for activities with more static assets that can be divorced from the game world: a character on a t-shirt or the use of an OST in a video not connected with the game. As such, branding (and perhaps ancillary concerns in trademark) are more apparently important considerations in UGC policy as activities to be constrained, despite the perception and framing that these are primarily copyright-related activities.

While this realignment of rewards provokes policymakers to force a re-interpretation of commerciality and fairness in copyright doctrine, it is fundamentally built on shaky foundations. In interrogating the question of who should be rewarded for the creation of UGC, this opens the paradox of the concept of UGC itself, as situating the user as an authorial creator, whose creativity is simultaneously treated both in copyright and contract as an excused allowance rather than the recipient of a lawful entitlement: the title, and exclusivity, of an author. This is indicative of a conceptual strain on our legal vocabulary as we attempt to articulate the slippery difference between the ‘author of a work’ and the ‘content creator’. Importing such definitions into copyright doctrine is dangerous precisely because of this contradictory nature; the legal treatment of UGC risks encroaching on principles of aesthetic neutrality by (indirectly perhaps) preferencing professionalism over amateurism through the grant of authorship. For this reason, this article does not necessarily argue that UGC policies, or the concept of merit-based monetisation, are better or worse solutions than the default law of copyright, and the delicate balance it seeks to maintain. In many ways, the UGC policies surveyed here, in manifesting openness, are in fact reflective of an uncertainty inherent in copyright law, which cannot be remedied with the glacial pace of policymaking. Instead, this article suggests that UGC policies are a conduit through which we can explore, and challenge, contradictory and unhelpful definitions of UGC, which can be used to deprive users of the receipt of either an authorial grant, or the benefit of a copyright exception.

References

Ahuja, N. (2017). Commercial creations: The role of end user license agreements in controlling the exploitation of user generated content. John Marshall Review of Intellectual Property Law, 16(4), 382–410.

Alae-Carew, N. (2020). Intellectual property and ‘Terms of Trade’: The challenges for entertainment businesses in the emerging platform economy. CREATe research paper 2020/5. Zenodo, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.3901129

Aplin, T., & Bently, L. (2020). Global mandatory fair use: The nature and scope of the right to quote copyright works(1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108884099

Bethesda Softworks LLC. (n.d.). Bethesda Creation Club. Bethesda Creation Club. https://creationclub.bethesda.net/

Chapdelaine, P. (2017). Copyright user rights: Contracts and the erosion of property (First edition). Oxford University Press.

Craig, C. (2011). Copyright, communication and culture: Towards a relational theory of copyright law. Edward Elgar.

Creative Commons Corporation. (2009). Defining “Noncommercial”: A study of how the online population understands “Noncommercial Use” (pp. 1–119) [Report]. https://mirrors.creativecommons.org/defining-noncommercial/Defining_Noncommercial_fullreport.pdf

Deng, Z., & Li, Y. (2021). Players’ rights to game mods: Towards a more balanced copyright regime. Computer Law & Security Review, 43, 105634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2021.105634

Diaz, A. (2022, February 3). Nintendo crushes fan-favourited game music YouTube channel with thousands of copyright claims. Polygon. https://www.polygon.com/22916040/nintendo-video-game-music-osts-youtube-gilvasunner-copyright-takedown

Dibbell, J. (2006). Owned!: Intellectual property in the age of eBayers, gold farmers, and other enemies of the virtual state or, how I learned to stop worrying and love the end-user license agreement. In J. M. Balkin & B. S. Noveck (Eds.), The state of play. Law, games, and virtual worlds (pp. 137–145). New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9780814739075.003.0010

Erickson, K. (2014). User illusion: Ideological construction of ‘user-generated content’ in the EC consultation on copyright. Internet Policy Review, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2014.4.331

Fiesler, C. (2018). Everything I needed to know: Empirical investigations of copyright norms in fandom. IDEA – The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Centre for Intellectual Property, 59(1), 65–87.

Fowler, H. (2020, July 15). Third-person shooter: In-game photography is becoming an avant-garde art form. Digital Trends. https://www.digitaltrends.com/gaming/in-game-photography-art/

Frosio, G. (2020). Reforming the C-DSM reform: A user-based copyright theory for commonplace creativity. IIC - International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law, 51(6), 709–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40319-020-00931-0

Furgal, U., Kretschmer, M., & Thomas, A. (2020). Memes and parasites: A discourse analysis of the copyright in the Digital Single Market Directive. CREATe working paper 2020/10. Zenodo, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.4085050

Gandola, K. (2022, July 3). What is the average salary of a Twitch streamer? Net Influencer. https://www.netinfluencer.com/average-salary-of-a-twitch-streamer/

Gervais, D. J. (2009). The tangled web of UGC: Making copyright sense of user-generated content. Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law, 11(4), 841–870. https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1719&context=faculty-publications

Gibson, J. (2006). Creating selves: Intellectual property and the narration of culture. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Creating-Selves-Intellectual-Property-and-the-Narration-of-Culture/Gibson/p/book/9781138264465

Harbinja, E. (2014). Virtual worlds players – Consumers or citizens? Internet Policy Review, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2014.4.329

Iljadica, M. (2020). User generated content and its authors. In T. Aplin (Ed.), Research handbook on intellectual property and digital technologies (pp. 163–185). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781785368349.00015

Irwin, D. (2021). The best Cyberpunk 2077 mods. PCGamesN. https://www.pcgamesn.com/cyberpunk-2077/mods-best

Lastowka, G. (2008). User-generated content and virtual worlds. Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law, 10(4), 893–917.

Lastowka, G. (2012). Minecraft as web 2.0: Amateur creativity & digital games. In D. Hunter, R. Lobato, M. Richardson, & J. Thomas (Eds.), Amateur media. Social, cultural and legal perspectives. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203112021

Lastowka, G. (2013). Copyright law and video games: A brief history of an interactive medium. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2321424

Marcus, T. D. (2008). Fostering creativity in virtual worlds: Easing the restrictiveness of copyright for user-created content. NYLS Law Review, 52(1), 67–92.

Meese, J. (2018). Authors, users, and pirates: Copyright law and subjectivity. The MIT Press.

Mezei, P., & Harkai, I. (2022). End-user flexibilities in digital copyright law – An empirical analysis of end-user license agreements. Interactive Entertainment Law Review, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.4337/ielr.2022.0003

OECD. (2007). Participative web and user-created content: Web 2.0, wikis and social networking [Study]. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd.org/sti/ieconomy/participativewebanduser-createdcontentweb20wikisandsocialnetworking.htm

Plunkett, L. (2022, March 20). Destiny copyright takedowns go rogue, are even hitting Bungie videos. Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/bungie-destiny-2-youtube-copyright-takedown-affiliate-c-1848678292

Quintais, J. P., Frosio, G., van Gompel, S., Hugenholtz, B., Husovec, M., Jütte, B. J., & Senftleben, M. (2019). Safeguarding user freedoms in implementing Article 17 of the Copyright in the Digital Single Market Directive: Recommendations from European academics. JIPITEC – Journal of Intellectual Property, Information Technology and E-Commerce Law, 10(3), 277–282.

Saab, H. (2021, August 16). 10 most popular gaming YouTubers, ranked By subscribers. Screen Rant. https://screenrant.com/most-popular-gaming-youtubers-ranked-by-subscribers/

Smith, D. (2022, April 19). Someone called ‘Let Her Solo Me’ is tricking Elden Ring players into thinking the great one has arrived. Kotaku. https://www.kotaku.com.au/2022/04/let-her-solo-me-tricking-players/

Thomas, A. (2021). A question of (e)sports: An answer from copyright. Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, 15(12), 960–975. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiplp/jpaa157

Wyatt, R. (2021, October 29). Upping our gaming [Blog]. YouTube Official Blog. https://blog.youtube/inside-youtube/innovation-series-gaming/

ZombieAli. (2019, March 1). Thomas the Tank Engine Over Mr X. Nexus Mods. https://www.nexusmods.com/residentevil22019/mods/62

Appendix

|

Game Title |

Rightsholder |

Dataset |

UGC Policy Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Dota 2 |

Valve |

eSports |

Valve, ‘Steam Subscriber Agreement’ <https://store.steampowered.com/subscriber_agreement/> Valve, ‘Valve Video Policy’ <https://store.steampowered.com/video_policy> |

|

Fortnite |

Epic Games |

eSports |

Epic Games, ‘Fortnite End User License Agreement’ <https://www.epicgames.com/fortnite/en-US/eula> Epic Games, ‘Fan Content Policy’ <https://www.epicgames.com/site/en-US/fan-art-policy> |

|

League of Legends |

Riot Games |

eSports |

Riot Games, ‘League of Legends Terms of Use’ <https://na.leagueoflegends.com/en/legal/termsofuse> Riot Games, ‘Legal Jibber Jabber’ <https://www.riotgames.com/en/legal> |

|

Starcraft II |

Blizzard |

eSports |

Blizzard, ‘End User License Agreement’ <https://www.blizzard.com/en-gb/legal/08b946df-660a-40e4-a072-1fbde65173b1/blizzard-end-user-license-agreement> Blizzard, ‘Terms and Conditions of Fan Art Submissions to Blizzard Entertainment’ <https://www.blizzard.com/en-gb/legal/a03da66c-273f-4a11-b18c-869db5b53688/terms-and-conditions-of-fan-art-submissions-to-blizzard-entertainment> Blizzard, ‘Video Policy’ <https://www.blizzard.com/en-gb/legal/2068564f-f427-4c1c-8664-c107c90b34d5/blizzard-video-policy> |

|

PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds |

PUB G Corporation |

eSports |

PUB G, ‘End-User License Agreement’ <https://www.pubg.com/eula/> PUB G, ‘Using PLAYERUNKNOWN’S BATTLEGROUNDS in Player-Created Content’ <https://www.pubg.com/player-created-content/> |

|

Arena of Valor |

Proxima Beta (subsidiary of Tencent) |

eSports |

Proxima Beta, ‘Arena of Valor – Terms of Service’ <https://www.arenaofvalor.com/terms.html> |

|

Rainbow Six Siege |

Ubisoft |

eSports |

Ubisoft, ‘End User License Agreement’ <https://legal.ubi.com/eula/en-GB> Ubisoft, ‘Terms of Use’ <https://legal.ubi.com/termsofuse/en-GB> Ubisoft, ‘Video Policy’ <https://www.ubisoft.com/en-us/videopolicy.html> |

|

Rocket League |

Psyonix |

eSports |

Psyonix, ‘End User License Agreement’ <https://www.psyonix.com/eula/> Psyonix, ‘Terms of Use’ <https://www.psyonix.com/tou/> |

|

SMITE |

Hi-Rez Studios |

eSports |

Hi-Rez, ‘End User License Agreement’ <https://web2.hirez.com/hirez-studios/legal/SMITE-End-User-License-Agreement-2016-10-21.pdf> Hi-Rez, ‘Hi-Rez Studios Policy for Streaming Videos and VODS (videos-on-demand)’ <https://web2.hirez.com/hirez-studios/legal/Hi-Rez-Studios-Policy-for-Streaming-Videos-and-VODs-Videos-on-Demand-7-12-18.pdf> Hi-Rez, ‘FAQs’ <https://www.hirezstudios.com/legal> |

|

Call of Duty: Black Ops 4 |

Activision (founded 1979) |

eSports |

Activision, ‘Terms of use’ <https://www.activision.com/uk/en/legal/terms-of-use> |

|

Halo 5: Guardians |

Microsoft Game Studios |

eSports |

Microsoft, ‘Terms of Sale’ <https://www.microsoft.com/en-gb/storedocs/terms-of-sale> Microsoft, ‘Community Standards for Xbox’ <https://www.xbox.com/en-US/legal/community-standards> Microsoft, ‘Game Content Usage Rules’ <https://www.xbox.com/en-us/developers/rules> Microsoft, ‘Services Agreement’ <https://www.microsoft.com/en-gb/servicesagreement#serviceslist> |

|

Magic: The Gathering Arena |

Wizards of the Coast |

eSports |

Wizards of the Coast, ‘Magic Online End User License Agreement and Software License’ <https://magic.wizards.com/en/mtgo/eula> Wizards of the Coast, ‘Fan Content Policy’ <https://company.wizards.com/en/legal/fancontentpolicy> Wizards of the Coast, ‘Code of Conduct’ <https://company.wizards.com/legal/code-conduct> |

|

World of Tanks |

Wargaming |

eSports |

Wargaming, ‘End User Licence Agreement’ <https://legal.eu.wargaming.net/eula/?_ga=2.226753625.519148912.1591803691-1999682024.1591803690> Wargaming, ‘Game Rules’ <https://legal.eu.wargaming.net/en/game-rules/> |

|

Apex Legends |

EA Games |

eSports |

EA, ‘Electronic Arts User Agreement’ <https://tos.ea.com/legalapp/WEBTERMS/US/en/PC/> |

|

Shadowverse |

Cygames |

eSports |

Cygames, ‘Service Agreement’ <https://shadowverse.com/terms.php> |

|

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt |

CD Projekt Red |

Video game |

CD Projekt Red, ‘User Agreement’ <https://regulations.cdprojektred.com/en/user_agreement> CD Projekt Red, ‘Video Policy’ <https://support.cdprojektred.com/en/witcher-3/playstation/content-policies/issue/830/video-policy> |

|

The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim |

Bethesda |

Video game |

Bethesda, ‘End User Agreement (EULA)’ <https://bethesda.net/data/eula/en.html> Bethesda, ‘Zenimax Media Terms of Service’ <https://bethesda.net/en/document/terms-of-service> Bethesda, ‘Code of Conduct’ <https://bethesda.net/en/document/code-of-conduct> Bethesda, ‘Video Policy’ <https://bethesda.net/en/article/3XrnHrB0iAesac8844yeuo/bethesda-video-policy> |

|

Red Dead Redemption II |

Rockstar Games |

Video game |

Rockstar Games, ‘Limited Software Warranty and License Agreement’ <https://www.rockstargames.com/eula> Rockstar Games, ‘Terms & Conditions’ <https://www.rockstargames.com/legal> Rockstar Games, ‘Policy on posting copyrighted Rockstar Games materials’ <https://support.rockstargames.com/articles/200153756/Policy-on-posting-copyrighted-Rockstar-Games-material> |

|

The Last of Us |

Sony Interactive Entertainment |

Video game |

Sony, ‘Software License’ <https://www.playstation.com/en-us/legal/softwarelicense/> Sony, ‘Software Usage Terms’ <https://www.playstation.com/en-gb/legal/software-usage-terms/> |

|

Batman: Arkham City |

Warner Brothers Interactive Entertainment |

Video game |

WB Games Inc, ‘End User License Agreement’ <https://legal.wbgames.com/wbgames-legal/epic/eula/eula_epic_en_NZ.html> WB Games Inc, ‘Terms of Use’ <https://policies.warnerbros.com/terms/en-us/html/terms_en-us_1.2.0.html> |

|

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild |

Nintendo |

Video game |

Nintendo, ‘End User License Agreement’ <https://www.nintendo.com/consumer/info/en_na/docs.jsp?menu=3ds&submenu=ctr-doc-eula> Nintendo, ‘Intellectual Property’ <https://www.nintendo.co.uk/Legal-information/Intellectual-Property/Intellectual-Property-Policy-625951.html> Nintendo, ‘Nintendo Game Content Guidelines for Online Video & Image Sharing Platforms’ <https://www.nintendo.co.jp/networkservice_guideline/en/index.html> Nintendo, ‘Nintendo's Anti-Piracy Programme’ <https://www.nintendo.co.uk/Legal-information/Nintendo-s-Anti-Piracy-Programme/Nintendo-s-Anti-Piracy-Programme-732261.html> |

|

Minecraft |

Mojang |

Video game |

Mojang, ‘Minecraft End User License Agreement’ <https://account.mojang.com/documents/minecraft_eula> Mojang, ‘Brand and Asset Usage Guidelines for our Games’ <https://account.mojang.com/terms#brand> |

|

Borderlands 2 |

Take2 |

Video game |

Take2, ‘Limited Software Warranty and License Agreement’ <https://www.take2games.com/eula/> Take2, ‘Take-Two Interactive Software Inc Terms of Service’ <https://www.take2games.com/legal> |

|

Dark Souls III |

Bandai Namco |

Video game |

Bandai Namco, ‘Terms of Use’ <https://en.bandainamcoent.eu/terms-of-use> |

|

Resident Evil 2 (Remake) |

Capcom |

Video game |

Capcom, ‘End User License Agreement’ <http://game.capcom.com/eula/eng.html Capcom, ‘FAQ’ <http://www.capcom-europe.com/faq/> |

|

Superhot |

Superhot Team |

Video game |

Superhot Team, ‘End User License Agreement’ <https://superhotgame.com/eula/> |

|

Undertale |

Toby Fox |

Video game |

Toby Fox and YoYo Games, ‘Undertale EULA’ <https://store.steampowered.com/eula/391540_eula_0> |

|

Cuphead |

Studio MDHR |

Video game |

Studio MDHR, ‘Cuphead Video Streaming Policy’ <http://studiomdhr.com/video-streaming-policy/> |

|

Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain |

Konami |

Video game |

Konami, ‘Terms of Use: Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain’ <https://www.konami.com/mg/mgs5/tpp/_common_all/eula/tppps3web/eula/eula.en.html> |

|

Outlast |

Red Barrels |

Video game |

Red Barrels, ‘Message to YouTubers’ <https://redbarrelsgames.com/contact/> |

Add new comment