Cranks, clickbait and cons: on the acceptable use of political engagement platforms

Abstract

NationBuilder connects voters, politicians, volunteers and staffers in an integrated digital system. Political parties across the globe use it to manage data and campaigns. Unlike most political technology providers, NationBuilder is nonpartisan and sells to anyone. Given recent controversy around political technology, this paper looks for empirical examples of questionable use. Drawing on a 2017 scan of NationBuilder installations globally, the study identifies three questionable uses as: (1) a mobilisation tool for hate or groups targeting cultural or ethnic identities, (2) a profiling tool for deceptive advertising or stealth media, and (3) a fundraising tool for entrepreneurial journalism. These questionable uses may require NationBuilder to revise its ‘Acceptable Usage Policy’ and raises broader questions about the responsibilities of political technology firms to liberal democracy.This paper is part of Data-driven elections, a special issue of Internet Policy Review guest-edited by Colin J. Bennett and David Lyon.

Introduction

Shortly after Donald Trump won the US presidency, Jim Gilliam (2016), the late president of start-up 3DNA, posted a message on its blog titled “Choosing to Lead”. Gilliam congratulated the “three thousand NationBuilder customers who were on the ballot last week”. These customers subscribed to 3DNA’s NationBuilder service that provides a political engagement platform connecting voters, politicians, volunteers and staffers in an integrated online service. The post continues:

Many of you – including President-elect Donald Trump and all three of the other non-establishment presidential candidates – were outsiders. And that’s why this election was so important. Not just for people in the United States, but for people all over the world. This election unequivocally proves that we are in a new era. One where anyone can run and win. (Gilliam, 2016)

Like many posts from NationBuilder, Gilliam celebrated the company’s mission to democratise access to new political technology, bringing in these outsiders.

Gilliam’s post demonstrates faith that being open is a corporate value as well as a business model. As its mission states today, NationBuilder sells “to everyone regardless of race, age, class, religion, educational background, ideology, gender, sexual orientation or party”. Their mission encapsulates a corporate belief in the democratic potential of their product, one available to anyone, much to the frustration of partisans and other political insiders on both sides who tend to guard access to their innovative technologies (Karpf, 2016b).

Gilliam’s optimism matters globally. Political parties worldwide use NationBuilder as a third-party solution to manage its voter data, outreach, website, communications and volunteer management. As of 3 December 2019, NationBuilder reported that in 2018 it was used to send 1,600,000,000 emails, host 341,000 events and raise $401,000,000 USD across 80 countries. The firm has also raised over $14 million US dollars in venture capital partially based on the promise that it will democratise access to political engagement platforms. Unlike most of its competitors, NationBuilder is a nonpartisan political engagement platform. NationBuilder is one of the few services actively developed and promoted as nonpartisan and cross-sectoral. Conservative, liberal and social democratic parties across the globe use NationBuilder, as the company emphasises in its corporate materials (McKelvey and Piebiak, 2018).

By letting outsiders access political technology, might NationBuilder harm politics in its attempts to democratise it? Now is the time to doubt the promise of political technologies. Platform service providers like NationBuilder are the object of significant democratic anxieties globally, rightly or wrongly (see Adams et al., 2019, for a good review of current research). The political technology industry has been pulled into a broad set of issues including, according to Colin Bennett and Smith Oduro-Marfo: “the role of voter analytics in modern elections; the democratic responsibilities of powerful social media platforms; the accountability and transparency for targeted political ads; cyberthreats to the through malicious actors and automated bots” (2019, pp. 1-2). Following the disclosures of malpractice by Cambridge Analytica and AggregateIQ, these public scandals have pushed historic concerns about voter surveillance, non-consensual data collection and poor oversight of the industry to the fore (Bennett, 2015; Howard, 2006; White, 1961).

My paper questions NationBuilder’s corporate belief that better access to political technology improves politics. In doing so, I add acceptable use of political technology to the list of concerns about elections and campaigns in the digital age. Even as Daniel Kreiss (2016) argues, campaigns are technologically-intensive, there have been no systematic studies of how a political technology is used, particularly internationally. My paper reviews the uses of NationBuilder worldwide. It offers empirical research to understand the real world of a contentious political technology and offers grounded examples of problematic or questionable uses of a political technology. NationBuilder is a significant example, as I discuss, of a nonpartisan political technology firm as opposed to its partisan rivals.

The paper uses a mixed method approach to analyse NationBuilder’s use. Methods included document analysis, content analysis and a novel use of web analytics. To first understand real world use, the study collected a list of 6,435 domains using NationBuilder as of October 2017. The study coded the 125 most popular domains by industry and compared results to corporate promotional materials, looking for how actual use differed from its promoted uses. The goal was to find questionable uses of NationBuilder. Questionable, through induction, came to mean uses that might violate liberal democratic norms. By looking at NationBuilder’s various uses, the review found cases at odds with normative and institutional constraints that allow for ‘friendly rivalry’ or ‘agonism’ in liberal democratic politics (Rosenblum, 2008; Mouffe, 2005). These constraints include a free press, individual rights such as privacy as well as a commitment to shared human dignity.

My limited study finds that NationBuilder can be used to undermine privacy rights and journalistic standards while also promoting hatred. The scan identified three problematic uses as: (1) a mobilisation tool for hate groups targeting cultural or ethnic identities; (2) a profiling tool for deceptive advertising or stealth media and; (3) a fundraising tool for entrepreneurial journalism. These findings raise issues about acceptable use and liberal democracy. For example, I looked for cases of NationBuilder being used by known hate groups inspired by recent concerns about the rise of the extreme right (Eatwell and Mudde, 2004) as well as the use of NationBuilder by news websites reflecting the changing media system (Ananny, 2018).

My findings suggest that NationBuilder may be a democratic technology, without being a liberal one. The traditions of liberalism and democracy are separate and a source of tension according to democratic theorist Chantal Mouffe. “By constantly challenging the relations of inclusion implied by the political constitution of 'the people' - required by the exercise of democracy”, Mouffe writes, “the liberal discourse of universal human rights plays an important role in maintaining the democratic contestation alive” (2009, p. 10). NationBuilder’s democratic mission of being open to outsiders then is at odds with a liberal tradition that pushes fraud, violence and hatred outside respectable politics.

While the paper identifies problems, it does not offer much in the way of solutions. Remedies are difficult and certainly not at NationBuilder’s global scale. As I discuss later, NationBuilder is not responsible for how it is used. The most immediate remedies might be based on corporate social responsibility. To this end, this paper provides three recommendations for revisions to 3DNA’s acceptable use policy to address these questionable uses: (1) reconcile its mission statement with its prohibited uses; (2) require disclosure on customers’ websites; and (3) clarify its relation to domestic privacy law as part of a corporate mission to improve global privacy and data standards. These reforms suggest that NationBuilder’s commitment to non-partisanship needs clarification and that the acceptable use of political technology is fraught – a dilemma that should become a central debate. Political technology firms – NationBuilder and its competitors – must understand that liberal democratic technologies are part of what Bennett and Oduro-Marfo describe as “the political campaigning network”. They continue, “contemporary political campaigning is complex, opaque and involves a shifting ecosystem of actors and organisations, which can vary considerably from society to society” (2019, p. 54). Companies ultimately must consider their obligations to liberal democracy, a political system made possible by technologies like the press and the internet (albeit imperfectly).

The acceptable use of politicised, partisan and nonpartisan technology

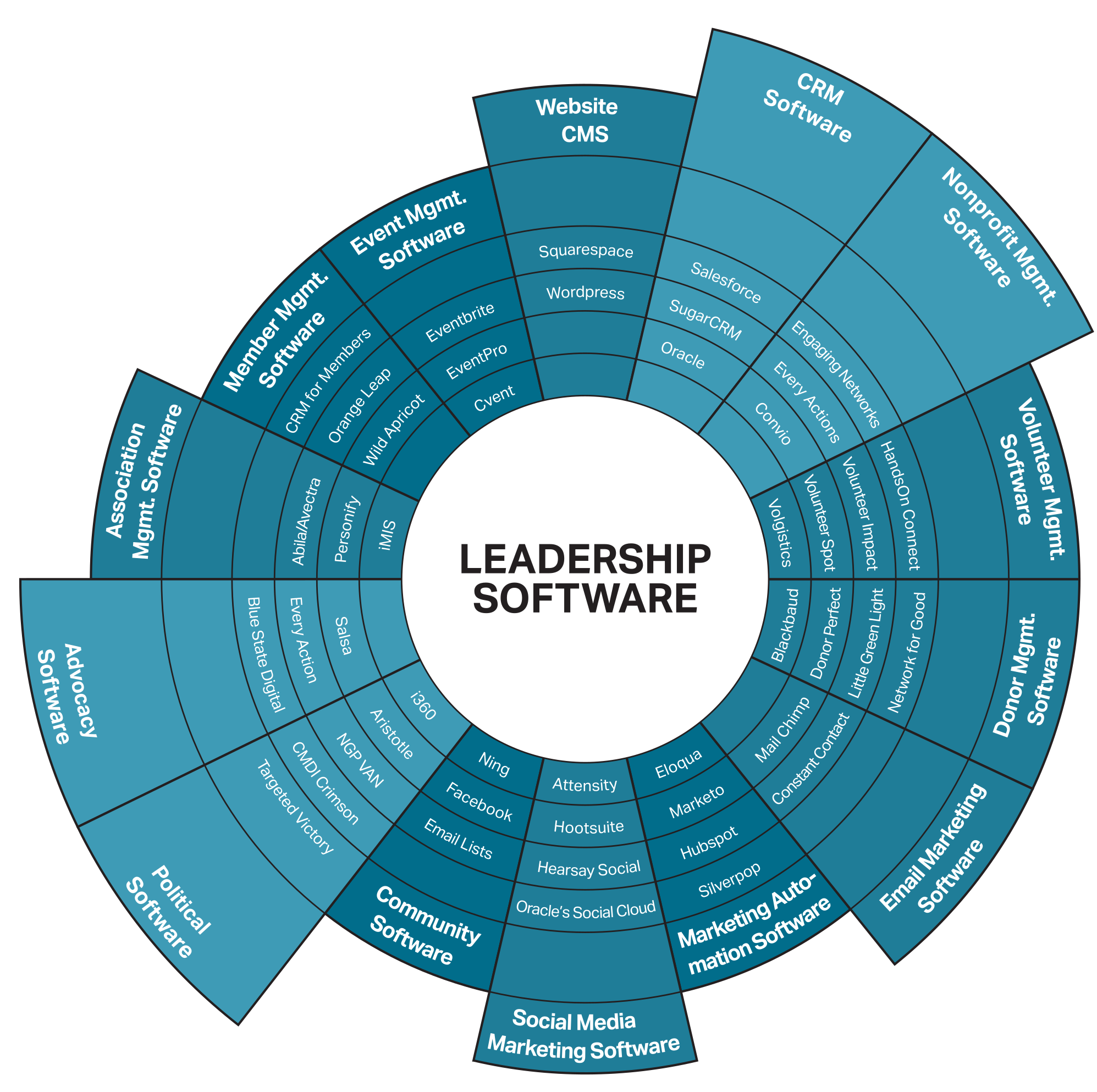

The political technology industry is central to the era of technology-intensive campaigning found in the United States and across many Western democracies (Baldwin-Philippi, 2015; Karpf, 2016a; Kreiss, 2016). The industry itself has been a staple of political consultancy throughout modern campaigning. From laser letters for direct mail to apps for canvassing, political technology firms promise to bring efficiency to an otherwise messy campaign (D. W. Johnson, 2016; Kreiss and Jasinski, 2016). NationBuilder itself provides a good summary of this industry in a marketing slide reproduced in Figure 1.

The figure illustrates the numerous practices and sectors drawn into politics as well as the migration of practices. These services help campaigns analyse data and make strategic decisions, principally around advertising buys. Many of these firms position themselves as the primary medium of a campaign, creating a platform connecting voters, politicians, volunteers and staff (Baldwin-Philippi, 2017; McKelvey and Piebiak, 2018). Political technology providers blur the boundaries between nonprofit management, political campaigning and advocacy as well as illustrating the taken-for-grantedness of marketing as a political logic (Marland, 2016).

Political technology firms may be divided between: politicised firms, partisan firms, and nonpartisan firms. Politicised firms sell software or services not explicitly designed for politics put to political ends. These can include payment processors like PayPal or Stripe, web hosting companies like Cloudflare and social media platforms that allow political advertising and political mobilisation. NationBuilder’s slide reproduced in Figure 1 includes some further examples of politicised firms providing social media management software, email marketing software and website content management systems. Technologies like NationBuilder are purpose-built for politics, listed as Political Software in Figure 1. These firms can be split further between partisan firms that work only for conservative, liberal or progressive campaigns and nonpartisan firms. In a market dominated by partisan affiliation, NationBuilder and other nonpartisan companies like Aristotle International and ActionKit are significant. They attempt to be apolitical political technologies.

Political technologies raise added concerns in respect to liberal democratic norms. Who should have access to these services, and how should these services be used? New technologies afford campaigns new repertoires of action that may undermine campaign spending limits, norms around targeting or the privacy rights of voters. Cambridge Analytica, for example, has rekindled longstanding debates about the democratic consequences of political technologies especially micro-targeting (Bodó, Helberger, and de Vreese, 2017; Kreiss, 2017) as well as stoking conjecture about the feasibility of psycho-demographics and its mythic promise of a new hypodermic needle (Stark, 2018).

Acceptable use is largely determined by partisan identity due to the limited scope of regulations on digital campaigning. Regulation for political technology is lacking (Bennett, 2015; Howard and Kreiss, 2010) and likely does not apply to a service provider like NationBuilder in the first place. Instead, so far partisanship has been regarded as the key mechanism to regulate the use of political technology. Most firms are partisan, working with only one party. Acceptable use of political technology is largely judged by its conformity to partisan values. As David Karpf explains, “political technology yields partisan benefits, and the market for political technologies is made up of partisans” (2016b, p. 209). Such partisanship functions as a professional norm about acceptable use, restricting access on partisan lines. Fellow partisans are acceptable, and, in what Karpf calls the zero-sum game of politics, rivals are unacceptable users. Indeed, partisanship is an important corporate asset. The major firm Aristotle International sued its competitor NGP VAN for falsely claiming it only sold to Democratic and progressive firms when it licensed its technologies to Republican firms as well. NGP VAN, the case alleged, was not as adherent a partisan firm as it claimed. The courts eventually dismissed the case (D’Aprile, 2011).

The tensions between partisan versus nonpartisan and politicised companies implicitly reveal a split in the values guiding acceptable use. On one side are firms committed to creating technology to advance their political values while on the other are firms trying to be neutral and to sell to anyone. In what might be seen as an act of community governance, progressive partisans argued that the software should not sell to non-progressive campaigns (Karpf, 2016a).

The lack of an expressed political agenda has caused politicised firms, in particular, to be mired in public scandals raising questions involving liberal democratic norms. A ProPublica investigation found that numerous technology firms supported known extremist groups, prompting Paypal and Plasso to cease offering services to groups identified days later (Angwin, Larson, Varner, and Kirchner, 2017a). That investigation only scratches the surface. A partial list of recent media controversies includes politicised firms being accused of spreading misinformation, aiding hate groups and easing foreign propaganda:

- Facebook’s handling of the Kremlin-affiliated Internet Research Agency misinformation campaigns during the 2016 presidential elections

- Hosting service Cloudflare removing Stormfront (Price, 2017)

- GoFundMe allowing a fraudulent campaign to build a US-Mexico border wall (Holcombe, 2019)

- GoFundMe removing anti-vaccine fundraising campaigns (Liao, 2019)

- YouTube’s handling of far-right videos and the circulation of the livestream of the Christchurch terrorist attack

In the academic literature, McGregor and Kreiss (2018) question the willingness of politicised firms to assist American presidential campaigns’ advertising strategies, examining how these companies understood their influence. Braun and Eklund (2019) meanwhile explore the digital advertiser's dilemma of trying to demonetise misinformation and imposter journalism. 1 The CitizenLab has addressed the responsibility of international cybersecurity firms in democratic politics, particularly the use of exploits to target dissidents. 2 Tusikov (2019) most directly explores the question of acceptable use by analysing how financial third parties, like PayPal, have developed their own internal policies to not serve hate groups.

For these reasons, NationBuilder is an important test case for the acceptable uses of political technology. NationBuilder, as discussed above, exemplifies the neutral position of many firms, trying to be in politics without being political. NationBuilder exemplifies the problem for both politicised and nonpartisan firms that let their commitments to openness and neutrality to supersede their responsibilities to be political and understand their responsibility to liberal democracy norms.

Why NationBuilder?

NationBuilder is an intriguing case because it encapsulates a particular American belief in the revolutionary promise of computing for politics that has driven the development and regulation of many major technology firms (Gillespie, 2018; Mosco, 2004; Roberts, 2019). NationBuilder is a venture capital–funded company promising to disrupt politics by democratising access to innovation. According to investor Ben Horowitz (2012), “NationBuilder is that rarest of products that not only has the potential to change its market, but to change the world”. He made these remarks in a 2012 post in which Horowitz’s firm announced $6.25 million USD in Series A funding for NationBuilder’s parent company 3DNA. NationBuilder’s late founder Jim Gilliam exemplifies the “romantic individualism” that Tom Streeter associates with a faith in the thrilling, revolutionary effect of computing. Gilliam was a fundamental Christian who found community through BBSs and eventually told his coming-of-age story in a viral video entitled “The Internet Is My Religion”. He later self-published a book co-authored with the company’s current president, Lea Endres. When generalised and situated as part of NationBuilder’s mission, Gilliam’s story exemplifies Streeter’s observation that “the libertarian’s notion of individuality is proudly abstracted from history, from social differences, and from bodies; all that is supposed not to matter. Both the utilitarian and romantic individualist forms of selfhood rely on creation-from-nowhere assumptions, from structures of understanding that are systematically blind to the collective and historical conditions underlying new ideas, new technologies, and new wealth” (Streeter, 2011, p. 24). NationBuilder still links to this video on its corporate philosophy page as of 3 December 2019.

NationBuilder’s mission synthesises its belief in for-profit social change and romantic individualism. According to NationBuilder’s mission page as of 7 January 2020, it wants to “build the infrastructure for a world of creators by helping leaders develop and organise thriving communities”. This includes a belief that: “The tools of leadership should be available to everyone. NationBuilder does not discriminate. It is arrogant, even absurd, for us to decide which leaders are “better” or “right” (NationBuilder, n.d.).

Their mission resembles Streeter’s discussion of the libertarian abstract sense of freedom that, in NationBuilder’s case, equates egalitarian access to a commercial service with a viable means for democratic reform. Whether nonpartisan or libertarian, NationBuilder has remained committed to this belief, defending its openness from critics, such as in Gilliam’s post from the introduction. In doing so, NationBuilder is at odds with former progressive clients and other political technology firms (Karpf, 2016b).

Methodology

My research combines document analysis, web analytics and content analysis to understand NationBuilder usage. The research team reviewed the company’s 2016, 2017 and 2018 annual reports and archived content from the NationBuilder website using the Wayback Machine. The team also turned to the web services tool BuiltWith. BuiltWith scans the million most-popular sites on the internet to detect what technologies they use. 3 BuiltWith generated a list of 6,435 web domains using NationBuilder on 10 October 2017. Research analysed BuiltWith’s data through two scans:

- Coding the top 125 websites (as ranked by Alexa, an Amazon company that estimates traffic on major websites) by industry and comparing the results with the publicised use cases in NationBuilder’s annual reports.

- Searching the full list of BuiltWith results for websites classified as extremist by ProPublica, itself informed by the Anti-Defamation League and the Southern Poverty Law Center (Angwin, Larson, Varner, and Kirchner, 2017b).

These methods admittedly offer a limited window into the use of NationBuilder. Rather than provide a complete scan of the NationBuilder ecosystem or track trends over time, this project sought to question whether NationBuilder has uses other than those advertised, and, if so, do these applications raise acceptability questions?

The coding schema classified uses of NationBuilder by industry. The schema developed out of a review of prior literature classifying websites (Elmer, Langlois, and McKelvey, 2012) as well as inductive coding developed by visiting the top fifty websites, paying special attention to self-descriptions, such as mission statements and “about us” sections, as well as other clues to a site’s legal status (as a non-profit or a political action committee) or its overt political party affiliation and stated political positions. In the end, each website in the sample was assigned one of ten codes:

- College or university: a higher education institution

- Cultural production: a site promoting a book, movie, etc.

- Educational organisation: a high school or below

- Government initiative: sites operated by incumbent political actors or elected officials that are explicitly tied to their work in government (i.e., not used for a re-election campaign)

- Media organisation: sites whose primary purpose is to publish or aggregate media content

- NGO: (non-governmental organisation) sites for organisations whose activities can reasonably be considered non-political; these are usually but not exclusively non-profits

- Other: sites that are unclassifiable (an individual’s blog, for example)

- Political advocacy group: organisations that are not directly associated with an official political party or campaign but nonetheless seek to actively affect the political process

- Political party or campaign: sites operated by a political party or dedicated to an individual politician’s electoral campaign

- Union: sites run by a labour union

Two independent coders classified the 125-website sample. Intercoder reliability was 88 percent with a Krippendorf’s alpha of 0.8425 (Freelon, 2010). Analysis below removed inconsistencies through consensus coding.

Findings

NationBuilder has applications not well presented in its corporate materials that raise acceptability issues. NationBuilder has been used as:

- a mobilisation tool for hate or groups targeting cultural or ethnic identities;

- a profiling tool for deceptive advertising or stealth media; and,

- a fundraising tool for entrepreneurial journalism.

None of these uses violate the official terms of use or acceptable use policy, a problem discussed later in the analysis, but they do provoke questions that may help improve its acceptable usage policies.

Results of scan 1: top industries found in most popular sites in the sample

The first scan, coding top domains by industry, found uses that differed from the corporate reporting. NationBuilder emphasises certain use cases in its annual report and marketing, signalling the authorised channels of circulation for the product as well as its popular applications. Reporting, however, has been inconsistent with the best data available from 2016. The 2016 Annual Report lists the following uses: political (40.80%), advocacy (24.60%), nonprofit (11.80%), higher education (11%), business (8.30%), association (2%), as well as government (1.50%). 4 NationBuilder also profiles “stand-out leaders” in all its annual reports. Politicians, advocacy groups and nonprofits mostly appear in the list. The 2017 list features six politicians out of ten slots, including the party of French President Emmanuel Macron, New Zealand's Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, and the leader of Canada's New Democratic Party Jagmeet Singh. Their successful campaigns resonate with NationBuilder's brand of political inclusion. In a new twist on the politics of marketing, NationBuilder also profiles businesses as stand-outs. AllSaints is a British fashion retailer that uses NationBuilder to connect with fans of the brand, especially to announce the opening of new stores.

Media outlets are more prominent in the findings than in 3DNA’s corporate materials. Two media outlets are in the top ten domains in our sample sorted by popularity as seen in Table 1. The third and fourth ranked sites are media organisations. Faith Family America is a right-of-centre news outlet, describing itself as “a real-time, social media community of Americans who are passionate about faith, family, and freedom”. The Rebel is a Canadian-based far-right news outlet, comparable to Breitbart in the US. Seven other media organisations appear in the sample, nine in total as seen in Table 2.

|

Name |

Domain |

Industry Code |

Country |

Alexa Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

American Heart Foundation |

NGO |

US |

10,525 |

|

|

NationBuilder |

Cultural production |

US |

20,791 |

|

|

City of Los Angeles |

Government initiative |

US |

33,419 |

|

|

Faith Family America |

Media organisation |

US |

65,980 |

|

|

The Rebel |

Media organisation |

CA |

71,126 |

|

|

Party of Wales |

Political party or campaign |

GB |

89,996 |

|

|

Lambeth Council |

Government initiative |

GB |

107,745 |

|

|

NALEO Education Fund |

Political advocacy group |

US |

112,071 |

|

|

Labour Party of New Zealand |

Political party or campaign |

NZ |

115,253 |

|

|

In Utero (film) |

Cultural production |

US |

120,394 |

Two of the questionable uses of NationBuilder relate to its move into journalism or at least the simulacra of journalism. Through these media outlets, NationBuilder becomes entangled in the ethics of entrepreneurial journalism. The term refers to the “embrace of entrepreneurialism by the world of journalism” (Rafter, 2016, p. 141).

|

Name |

Domain |

Alexa Rank |

|---|---|---|

|

Faith Family America |

65,980 |

|

|

The Rebel |

71,126 |

|

|

Thug Kitchen |

192,082 |

|

|

New Civil Rights Movement |

224,004 |

|

|

All Cute All the Time |

266,126 |

|

|

Inspiring Day |

330,692 |

|

|

Newshounds |

432,266 |

|

|

Brave New Films |

703,101 |

|

|

Mark Latham Outsiders |

763,959 |

Otherwise, findings resembled data from the 2016 annual report. Political, advocacy and nonprofits accounted for 77.2 % of NationBuilder’s customers in the annual report whereas non-governmental organisations, political advocacy groups, political party or campaign and union comprised 83.2% in the sample. Unlike the annual reports, the sample included nine media-based organisations out of the 125 sites, representing 7.2% of the findings. Other users were marginal. There was a curious absence of any brand ambassadors even though NationBuilder highlights these applications prominently in its annual reports and describes 1% of its customers as such in its 2017 report.

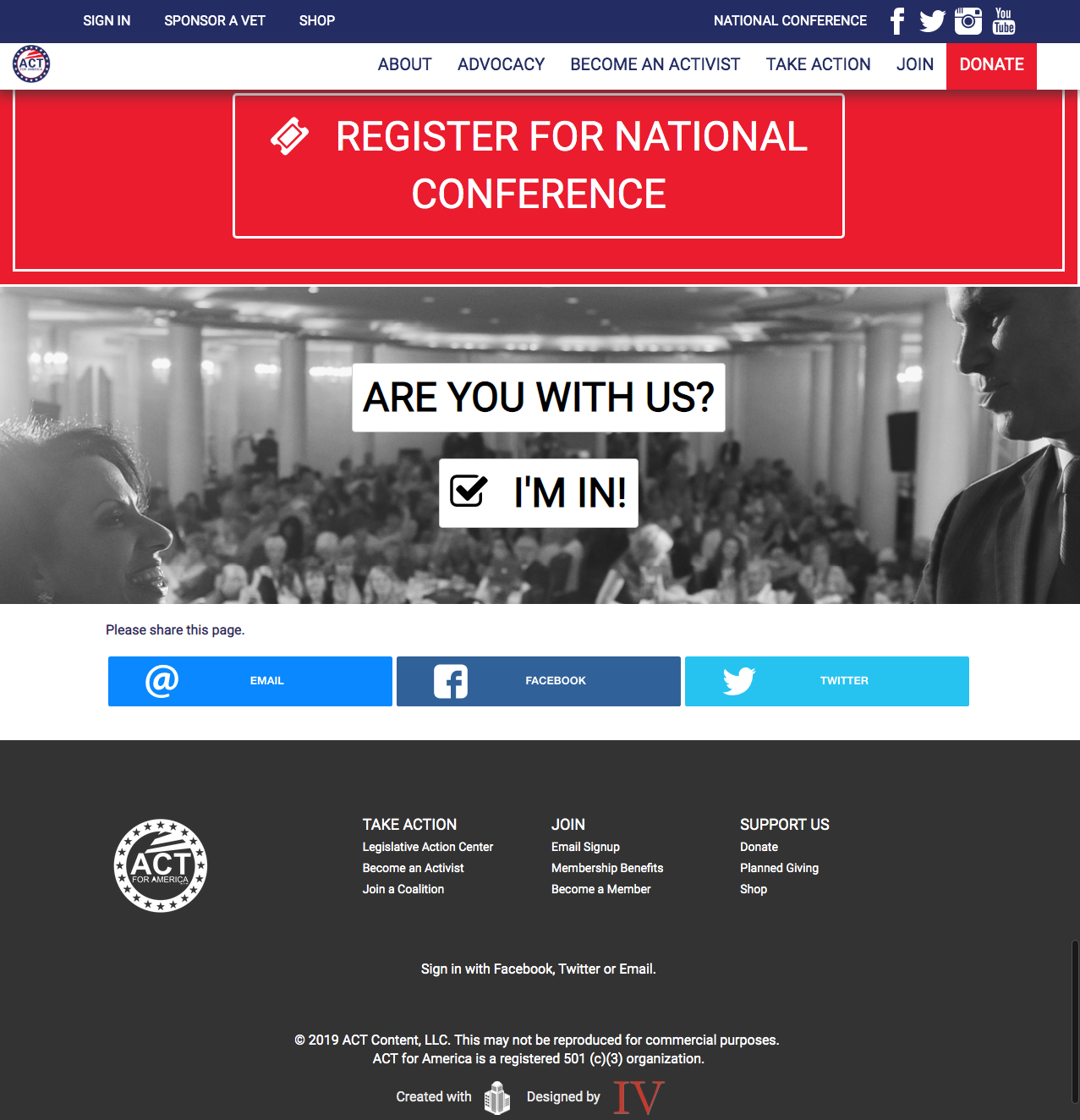

Results of scan 2: extremists or hate groups using NationBuilder

The second scan found one use case by a known hate group as defined by the Southern Poverty Law Center, Act for America (ranked 72nd in sample). The Southern Poverty Law Center describes the group as the “largest anti-Muslim group in America”. Act for America used NationBuilder until August 2018 when it switched to an open-source equivalent, Drupal and CiviCRM (cf. McKelvey, 2011). Act for America did not state the reason for the switch or reply to questions.

Covert political organising?

Three media outlets stood out in the sample: Faith Family America, Inspiring Day and All Cute All the Time. Each site used attention-grabbing headlines (also known as clickbait) to present curated news, updates about the British monarchy, and celebrity news that was respectively conservative, religious and innocuous (rather than cute). None of these sites listed staff in a masthead or provided many details about their reporting; instead, the sites encouraged users to join the community and promoted their Facebook groups.

All three outlets were owned by the company Strategic Media 21 (SM21) – a fact that was only apparent through examining the site’s identical privacy policies. Now offline, SM21 was based in San Jose, California. It seems to have been a digital marketing firm with two different web presences: one for content marketing and one for digital strategy. Neither site discloses much information about the company, but their business strategy seems to be manufacturing audiences for political advertisers. SM21 identifies demographics, then creates specific outlets, like Faith Family America for conservative voters, in the hope of building up a dedicated audience for advertising. Data broker L2 blogged about their 2016 partnership with SM21 on a targeted Facebook political advertising campaign. In this case, SM21 was acting in its digital strategy role, working with clients “on messaging, creative, plans out the buy and launches the campaign using your targeted list” (Westcott, 2016). These services have proved valuable. SM21 has received $2,418,592 USD in political expenditures since 2014 according to OpenSecrets. The biggest clients were the conservative Super PACs (political action committees) Vote to Reduce Debt, and Future in America.

Strategic Media 21 raises suspicions that NationBuilder’s data analytics might be used covertly, a kind of native advertising without the journalism. This might be an application of what Daniels calls cloaked websites “published by individuals or groups that conceal authorship or feign legitimacy in order to deliberately disguise a hidden political agenda” (2009, p. 661). Kim et al. describe similar tactics as stealth media, “a system that enables the deliberate operations of political campaigns with undisclosed sponsors/sources, furtive messaging of divisive issues, and imperceptible targeting” (2018, p. 2). By building these niche websites and corresponding Facebook groups that crosspost their content, SM21 has created a political advertising business. NationBuilder features might assist in this business; its Match feature connects email addresses with other social media accounts, and its Political Capital feature monitors these feeds for certain activities.

Suspicions that Strategic Media 21 used NationBuilder for its data mining features are likely true. According to emails released as part of a suit filed against Facebook by the Office of the Attorney General for the District of Columbia, Facebook employees discussed Cambridge Analytica, NationBuilder and SM21 as all being in violation of its data sharing arrangements (Wong, 2019). As one internal document dated 22 September 2015 explains,

One vendor offering beyond [Cambridge Analytica] we're concerned with (given their prominence in the industry ) is NationBuilder’s “Social Matching,” on which they've pitched our clients and their website simply says “Automatically link the emails in your database to Facebook, Twitter, Linkedin and Klout profiles, and pull in social engagement activity.” I'm not sure what that means, and don't want to incorrectly tell folks to avoid it, but it is definitely being conflated in the market with other less above board services. Can you help clarify what they're actually doing?

Employees worried that “these apps’ data-scraping activity [were] likely non-compliant” according to a reply dated 30 September 2015 and the thread actively debated the matter for months. Facebook employees singled out SM21 in a comment on 20 October 2015. It begins,

thanks for confirming this seems in violation. [REDACTED] mentioned there is a lot of confusion in the political space about how people use Facebook to connect with other offline sets of data. In particular, Strategic Media 21 has been exerting a good deal of pressure on one of our clients to take advantage of this type of appending.

These concerns ensued even as Facebook employees reacted to a Guardian article on 11 December 2015 entitled “Ted Cruz using firm that harvested data on millions of unwitting Facebook users” – one of the first stories to develop in the ongoing scandal involving Cambridge Analytica and Facebook data sharing (Davies, 2015). What ultimately happened to NationBuilder and Strategic Media 21 has not been disclosed to date. NationBuilder still advertises its social matching features. SM21, on the other hand, has gone offline, with its website available for purchase as of September 2019.

This evidence raises our first problem of acceptable use: should NationBuilder be used by covert or stealth media to enable the deceptive or non-consensual collection of data? Strategic Media 21 then parallels Cambridge Analytica where users unwittingly trained its profiles by filling out quizzes on Facebook (Cadwalladr and Graham-Harrison, 2018). Visiting websites running Strategic Media 21 and joining related groups might unwittingly inform advertising profiles harvested through NationBuilder. This is a serious privacy harm noted by a UK Information Commissioner’s Office (2018) report and an Information and Privacy Commissioner for British Columbia (2019) report that both raised the issue of social matching in their own reports on NationBuilder.

Advocacy, journalism or outrage?

NationBuilder has become entangled in the ethics of entrepreneurial journalism and the boundaries between editorial and fundraising through The Rebel, its Australian-affiliate Mark Latham’s Outsiders, and to a lesser extent the Newshounds (Hunter, 2016; Porlezza and Splendore, 2016). All sites rely on crowdsourcing, reminding their readers that they need financial support. Newshounds.us is a media watchdog blog covering Fox News that asks its visitors to donate to support its coverage. The Rebel is a Canadian news start-up, established at the closure of Sun News TV or what was called Fox News North. While start-ups, these outlets position themselves as journalism outlets. Newshounds makes mention of its editor’s journalism degree. The Rebel asks its visitors to subscribe and to help support its journalism.

The line between fundraising and journalism is a clear ethical concern for journalism. As Porlezza and Splendore note in a thoughtful review of accountability and transparency issues in entrepreneurial journalism, the industry has to deal with a challenge “that touches the ethical core of journalism: are journalists in start-ups able to distinguish between their different and overlapping goals of publisher, fundraiser and journalist?” (2016, p. 197). Crowdfunding challenges ethical practice by requiring journalists to pitch and report their stories to the public. At its most extreme, fundraising may tip journalism into what Berry and Sobieraj call outrage public opinion media, “recognisable by the rhetoric that defines it, with its hallmark venom, vilification of opponents, and hyperbolic reinterpretations of current events” (2016, p. 5). Reporting, in this case, becomes a means to outrage its audiences and channel that emotion into donations.

The Rebel, for example, blurred the line between financing a movement and a news outlet. In a now-deleted post on the NationBuilder blog, Torch Agency, the creative agency for The Rebel, explains NationBuilder’s role in launching what it called “Canada’s premier source of conservative news, opinion and activism”. The post continues,

In 36 hours, we built a fully-functional NationBuilder site complete with a database and communication headquarters... The result: through compelling content and top-notch digital tools, The Rebel raised over $100,000 CAD in less than twelve hours providing crucial early funding for its continuation.

The Rebel promised to use NationBuilder to better engage news audiences. The Rebel has repeatedly asserted its status as a journalism outlet against claims to the contrary. The Rebel enlisted the support of national press organisations, PEN Canada and Canadian Journalists for Free Expression, after being denied press credentials for a UN climate conference for being “advocacy journalism” (Drinkwater, 2016). In the Canadian province of Alberta, The Rebel successfully protested being removing from the media gallery because it wasn’t a “journalist source” (Edmiston, 2016).

The Rebel's response to a Canadian terrorist attack best frames the problem of distinguishing between advocacy, fundraising and journalism as well as NationBuilder's challenges in defining acceptable use. On 29 January 2017, a man entered a mosque in Québec City with an AK-47, killing six, seriously wounding five and injuring twelve people (Saminather, 2018). The Rebel launched the website QuebecTerror.com the next day. The initial page urged visitors to donate to send a Rebel reporter to cover the aftermath. The site, days after its claims had been discredited by other outlets, described the killing as inter-mosque violence based on a mistranslation of a public YouTube video. Rather than presenting itself as a journalistic report, the QuebecTerror website appeared as a conventional email fundraising pitch, depicting a dire reality – in this case a “truth” the mainstream media would not report – solvable through donations.

The language and matter of The Rebel’s reporting on the Québec terror attack resemble the tactics of outrage media, inflammatory rhetoric in this case complemented by a service to mobilise those emotions (Berry and Sobieraj, 2014). The Rebel’s response to the Québec terror attack then raises a different problem than journalists being uncomfortable in asking for money, as Hunter (2016) notes in a review of crowdfunding in journalism. Here fundraising overtakes reporting; stories are optimised for outrage. The problem is not new, but rather a consequence of the movement of practices between separate fields. Using the news to solicit funds is a known email marketing tactic. Emails that reacted to the news had the highest open rates according to analysis of Hillary Clinton’s email campaigning (Detrow, 2015). NationBuilder may streamline outrage tactics by channelling user engagement. Called a funnel or a ladder in marketing, NationBuilder has a path feature that tries to nudge user behaviour toward certain goals. Taken together, NationBuilder might ease this questionable form of crowdfunding in entrepreneurial journalism and encourage outrage tactics.

These concerns raise a second question: should NationBuilder be used in journalism, especially on hyper-partisan sites or outrage media already blurring the line between reporting, advocacy and fundraising? For its own part, fundraising ethics did cause turmoil at The Rebel. It suffered a scandal when a former correspondent accused the site of misusing funds, pointing to a disclaimer on the website that stated, “surplus funds raised for specific initiatives will be used for other costs associated with that particular project, such as website development, website hosting, mail, and other such expenses” (Gordon and Goldsbie, 2017). Seemingly, any campaign was part of a general pool of revenue, adding to concerns that certain stories might be juiced to bring in more money to general revenues.

These first two cases situate NationBuilder as part of the networked press. Ananny (2018) introduced the concept of the networked press to argue journalism exists within larger sociotechnical systems, of which NationBuilder is a part. Changes or disruption in these systems, evidenced through the rapid uptake of large social networking sites, do not necessarily imply increased press freedom and, instead require journalists’ practices to acknowledge and adapt to broader infrastructural changes. Just as outlets and journalists need to consider these changes, so too does NationBuilder in understanding how its technology is participating in the infrastructure of the networked press. As seen above, NationBuilder already participates in the ethical quandaries and its emphasis on mobilisation and fundraising may be ill-suited for journalistic outlets. NationBuilder might enable data collection and profiling without sufficient audience consent. NationBuilder might also tip the balance from journalism to outrage media by being a better tool to fundraise than publish stories. How does a firm like NationBuilder recognise its role in facilitating these transfers, particularly the expansion of marketing as the ubiquitous logic of cultural production? Should it ultimately be part of press infrastructure? Does using a political engagement platform ultimately improve journalistic practice? These matters require a more hands-on approach than that which NationBuilder presently offers.

Illiberal uses of political technology

Act for America engages in identity-based political advocacy, targeting American Muslims. Their mission includes immigration reform and combating terrorism. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, their leadership has questioned the right to citizenship of American Muslims, alluding to mass deportation. Politically such statements seem at odds with the rules of what political theorist Nancy Rosenblum calls the “regulated rivalry” of liberal democracy. To protect itself, a militant democracy needs to ban parties that if elected or capable of influencing government “would implement discriminatory policies or worse: strip opposition religious or ethnic groups of civil or political rights, discriminate against minorities (or majorities), deport despised elements of the population” (Rosenblum, 2008, p. 434). Act for America seems to have engaged in such acts in targeting Muslim Americans.

NationBuilder then faces a third existential question: should groups that mobilise hate have access to its innovations? Other firms, like PayPal, stopped offering Act for America services after ProPublica reported on their relationship (Angwin et al., 2017a). While defining hate might be a little more difficult for an American firm where there is no clear hate speech laws, NationBuilder operates in many countries with clear laws and could guide corporate policy. That these terms are left missing or undefined in 3DNA’s Acceptable Use Policy is troubling.

The more challenging question that faces the larger industry is what responsibility do service providers have for the speech acts made on their services? As Whitney Phillips and Ryan Milner (2017) reflect, “it is difficult…to know how best – most effectively, most humanely, most democratically – to respond to online speech that antagonises, marginalises, or otherwise silences others. On one level, this is a logistic question about what can be done… The deeper and more vexing question is what should be done” (2017, p. 201) This vexing question is a lingering one, echoing the origins of modern broadcasting policy, which begins with governments and media industries attempting to reconcile preserving free speech without propagating hate speech. The American National Association of Broadcasters established a code of conduct in 1939 in part to ban shows like Father Coughlin’s that aired speeches “plainly calculated or likely to rouse religious or racial hatred and stir up strife” (Miller, 1938, as cited in Brown, 1980, p. 203). The decision did not solve the problem, but rather established institutions to consider these normative matters.

NationBuilder is not merely a broadcaster or a communication channel, but a mobilisation tool. The use of NationBuilder by hate groups should trouble the wider political technology industry and the field of political communication. It is part of a tradition in democratic politics that media technology does not just inform publics, but cultivates them. As Sheila Jasanoff notes, American “laws conceived of citizens as being not necessarily knowing but knowledge-able–that is, capable at need of acquiring the knowledge needed for effective self-governance. This idea of an epistemically competent citizen runs through the American political thought from Thomas Jefferson to John Dewey and beyond” (Jasanoff, 2016, p. 239). Communication is about formation as much as information, of cultivating publics. NationBuilder punctuates an existential question for political technology: is it exceptional or mundane? Is it a glorified spreadsheet or a special class of technology? In short, if NationBuilder is an effective tool of political mobilisation, should it effectively mobilise hate?

From corporate social responsibility to liberal democratic responsibility

Finding solutions to the problematic cases above is part of an international debate about platform governance (DeNardis, 2012; Duguay, Burgess, and Suzor, 2018; Gillespie, 2018; Gorwa, 2019). Platform governance refers to the conduct of large information intermediaries and, by extension, the social impacts of publicly accessible and networked computer technology. Where human rights is one emerging value set for platform governance (Kaye, 2019), the international challenge now is to the appropriate ‘web of influence’ that might address human rights concerns and address the numerous regulatory challenges posed by large technology firms (Braithwaite and Drahos, 2000).

Options include external rules – such as fines and penalties through privacy, data protection or election law – and co-regulatory approaches, like codes of conduct and best practices, in addition to self-regulation, specifically corporate social responsibility and responsibilities bestowed for liability protection. Self-regulation dominates the status quo, at least in the US. The rules are largely self-written by platforms, in large part due to their public service obligations under the US Telecommunications Act (Gillespie, 2018). Companies, like Facebook, have acknowledged a need for changing, publicly calling for government regulation (Zuckerberg, 2018). Today, platforms in good faith moderate users in conversations under acceptable use rules. Users might be banned, suspended, surveilled, deprioritised or demonetised under acceptable use policies (Myers West, 2018). The stakes now involve a debate about the public obligations of platforms and whether they should self-police or be deputised to enforce government rules (DeNardis, 2012; Tusikov, 2017).

The regulation of firms like NationBuilder face even greater regulatory challenges as the field has been historically free from much oversight or responsibilities. Many western democracies did not consider political parties or political data to be under the jurisdiction of privacy law. Enforcement was also lacking. Even though political parties were regulated in Europe, regulators only took their responsibilities seriously after the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica scandal (Bennett, 2015; Howard and Kreiss, 2010). Even with new data protection laws, intermediaries still face limited liability as enforcement tends towards the user than the service provider. Service providers are exempt from liability or penalties for misuse, except in certain cases such as copyright. For its own part, NationBuilder claims zero liability for interactions and hosted content according to its Terms of Service.

Political engagement platforms do face an uncertain global regulatory context. On one hand, they function as service providers largely exempt from laws. On the other hand, international law is uneven and changing (for a recent review, see Bennett and Oduro-Marfo, 2019). Public inquiries in the United Kingdom and Canada have focused more on these companies and their status may be changing. A joint investigation of AggregateIQ by the Privacy Commissioner of Canada and the Information and Privacy Commissioner for British Columbia found that the third-party service provider “had a legal responsibility to check that the third-party consent on which they were relying applied to the activities they subsequently performed with that data” (2019, p. 22). The implication is that AiQ had a corporate responsibility to abide by privacy laws in the provision of its services. The same likely holds for NationBuilder.

Amidst regulatory uncertainty, corporate social responsibility might be the most immediate remedy to questionable uses of NationBuilder. Its mission today might be read as ‘functionalist business ethics’ that believe that the product in and of itself is a social good and that more access, or more sales, improves the quality of elections. Whereas other approaches to corporate social responsibility favour an integrative business ethics where “a company’s responsibilities are not merely restricted in one way or another to the profit principle alone but to sound and critical ethical reasoning” (Busch and Shepherd, 2014, p. 297). Where future debates might require consideration of NationBuilder’s obligations to liberal democracy, the next section considers how NationBuilder’s mission and philosophy might be clarified through the company’s acceptable use policy. NationBuilder might not have to become partisan, but it cannot be neutral toward these institutions of liberal democracy, at least if it wants to continue to believe in its mission to revolutionise politics.

Revising the Acceptable Use Policy is possible and has happened before. Clearly stating the relationship between its mission and prohibited uses would reverse past amendments that narrowed corporate responsibilities. The Acceptable Use Policy as of August 2019, last updated 1 May 2018, is more open than prior iterations. Most bans concern computer security, prohibiting uses that overload infrastructure or accessing data without authorisation. The policy does prohibit “possessing or disseminating child pornography, facilitating sex trafficking, stalking, troll storming, threatening imminent violence, death or physical harm to any individual or group whose individual members can reasonably be identified, or inciting violence”. Until 2014, 3DNA covered acceptable use as part of its terms of service; afterwards it became a separate document. Its Terms of Service agreement from 29 March 2011 banned specific user content including “any information or content that we deem to be unlawful, harmful, abusive, racially or ethnically offensive, defamatory, infringing, invasive of personal privacy or publicity rights, harassing, humiliating to other people (publicly or otherwise), libellous, threatening, profane, or otherwise objectionable” as well as a subsequently removed ban on posting incorrect information. These clauses were removed in the 2014 update that reduced prohibited uses to 15. These clauses have slowly been added back. The most recent acceptable usage policy, as of 1 May 2018, had 31 prohibited uses, adding back clauses regulating user activities.

Recommendation #1: Reconcile its mission statement with its prohibited uses

NationBuilder’s Mission is to connect anyone regardless of “race, age, class, religion, educational background, ideology, gender, sexual orientation or party”. By contrast, its Acceptable Use Policy does not consider the positive freedoms inferred in this mission that could conceivably prohibit campaigns aimed at excluding people from participating in politics. A revised Acceptable Use Policy should apply the implications of its corporate mission to its prohibited uses. Act for America, for example, targets its opponents by race and advocates for greater policing, terrorism laws and immigration enforcement that could disproportionately affect Muslim Americans, acting against NationBuilder’s vision of “a world where everyone has the freedom and opportunity to create what they are meant to create”. Revision might prohibit campaigns or parties targeting assigned identities like race, age, gender or sexual orientation, particularly when messages incite hate, while preserving customers’ right to campaign against ideology, party or other chosen or elective politicised issues. To achieve such a mission, NationBuilder may have to restrict access on political grounds (also called de-platforming) or to restrict certain features. 5

Harmonising its position on political freedom may prompt industry-wide reflection on the function of political technology. How do these services protect the liberal democratic institutions they ostensibly promise to disrupt? In finding shared values, NationBuilder has to consider its place in a partisan field. Can it navigate between parties to describe ethical campaigning, or, alternatively, must it find other companies with shared nonpartisan or libertarian values? The likely outcome either way is a code of conduct for digital campaigning similar to the Alliance of Democracies Pledge for Election Integrity or the codes of conduct of the American Association of Political Consultants or European Association of Political Consultants that discourage campaigns based on intolerance and discrimination. In doing so, NationBuilder might force partisan firms to be more explicit about their professional ethics.

Recommendation #2: Require disclosure on customers’ websites

NationBuilder should disclose when it is used even if it cannot decide if it should be used. Two out of the three questionable uses might have benefitted from the organisations’ disclosing their use of the political engagement platform, especially when used in journalism. At a minimum, NationBuilder should require sites to disclose using NationBuilder, ideally through an icon or other disclosure in the page’s footer that might create the possibility of public awareness (Ezrahi, 1999). NationBuilder might also consider requiring users to disclose what tracking features, such as Match and Political Capital, are enabled on the website not unlike the disclosure about data tracking under Europe’s Cookie Law that disclose a site’s use of the tracking tool.

NationBuilder might further standardise the reporting of uses found in its annual report and potentially release data in a separate report. Transparency reports have become an important, albeit imperfect, reporting tool in telecommunications and social media industries (Parsons, 2019). These reports, ideally, would continue the preliminary method used in this paper, breaking down NationBuilder’s use by industry over time and potentially expanding data collection to include other trends such as use by country, use by party and the popularity of features. Such proactive disclosure might also normalise greater transparency in a political technology industry known for its secrecy.

Recommendation #3: Clarify relationship to domestic privacy law

A revised acceptable use policy might define NationBuilder expectations for privacy rights both to explain its normative vision for privacy and improve its customers’ implementation of local privacy law. By contrast, the acceptable use policy currently prohibits applications that “infringe or violate the intellectual property rights (including copyrights), privacy rights or any other rights of anyone else (including 3DNA)”. The clause does not clarify the meaning of privacy rights or jurisdiction. Elsewhere 3DNA states that all its policies “are governed by the internal substantive laws of the State of California, without respect to its conflict of laws principles”. Such ambiguity confuses a clear interpretation of privacy rights, the law and regulation mentioned in the policy. A revised clause should state NationBuilder’s position on privacy as a human right, in such a way that it provides some guidance as to whether local law meets its standards and denies access in countries that do not meet its privacy expectations. Further, the acceptable use policy should also clarify that it expects customers to abide by local privacy law, and, in major markets, if it has any reporting obligations to privacy offices.

Clarifying its position on privacy rights recognises the important function NationBuilder plays in educating its customers on the law. NationBuilder may help implement “proactive guidance on best campaigning practices” recommended by Bennett and Oduro-Marfo (2019, p. 54). For its GDPR compliance, NationBuilder has built a blog and offers many educational resources to customers to understand how to campaign online and to respect the law. These posts clearly state that they are not legal advice, but they do help to interpret the law for practitioners. Similar posts could help clients understand if they should disable certain features in NationBuilder, such as Match or Political Capital, to comply with their domestic privacy law. Revisions to its Acceptable Use Policy might be another avenue for NationBuilder to educate its customers.

Adding privacy to its corporate mission may be a further signal of NationBuilder’s corporate responsibility. NationBuilder has an altogether different relationship to customer privacy than other advertising-based technology firms. Its revenues come from being a service provider and securing data. With growing pressure on political parties to improve their cyber-security, NationBuilder can help its clients better protect their voter data as well as call for better privacy protection in politics overall. Indeed, NationBuilder could advocate for privacy law to apply to its political clients to both simplify its regulatory obligations and reduce risk. Improving privacy may lessen its institutional risk of being associated with major privacy violations as well as simplifying the complex work of setting privacy rules on its own. As such, NationBuilder might be a possible global advocate for better privacy and data protection, a role to date unfulfilled long after public controversy.

Conclusion

This paper has reported the results of empirical research about the acceptable use of a political technology. The results demonstrate that political technologies have questionable uses involving their application within politics. Specifically when does a political movement exceed the limits of liberal democratic discourse? When are its uses in journalism and advertising unacceptable? The experiment demonstrates that harms to liberal democracy can be a reasonable way to judge technological risks. Liberal democratic norms are another factor to consider to the wider study of software and technological accountability (Johnson and Mulvey, 1995; Nissenbaum, 1994). These concerns have a long history. Norbert Wiener, who helped develop digital computing, warned against its misuse in Cold War America for the management of people (Wiener, 1966, p. 93). By comparison, science and technology scholar Sheila Jasanoff (2016) questions if the benefits of technological innovation outweigh the risks of global catastrophe, inequality, and human dignity. While catastrophic global devastation is commonly seen as a questionable use of technology (unless it concerns the climate), there is less consensus about how technology might undermine democracy, of which liberal democracy is just one set of norms. What democracy should be defended is debated (with fault lines drawn between representative, direct and deliberative democracy as well as between liberal and republican traditions) (Karppinen, 2013). My method helps to clarify this debate by finding inductively uses that might challenge many theories of democracy. Further research could extend the analysis to focus on particular concerns to different forms of democracy and democratic theories.

My specific recommendations for NationBuilder may improve the accountability of the political industry at large. Oversight is a major problem in the accountability of political platforms. My methods could easily be scaled to observe more companies and countries. No doubt privacy, information and election regulation could implement this approach as part of their situational awareness. The questionable uses here then offer uses to watch for:

- Does the technology facilitate or ease deceptive or non-consensual data collection?

- Does the technology undermine journalistic standards and consider its role in the networked press?

- Does the technology facilitate the mobilisation of hate groups?

Where remedies to these challenges may be unclear, at the very least ongoing monitoring could identify potential harms sooner than academic research.

Questionable uses of NationBuilder should trouble the company as well as the larger political technology industry and the field of political communication. Faith in political technologies has changed campaign practice in many democracies as well as attracted ongoing international regulatory attention concerned with trust and fairness during elections. Technologies like NationBuilder are premised on the value of communications to political engagement. They are designed to increase engagement and improve efficiency. NationBuilder and its peers are a special class of political technology and thus their obligations to liberal democratic values should be scrutinised. If 3DNA seeking to better politics suffers these abuses then what will come from political firms with less idealism?

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge Colin Bennett, the Surveillance Studies Centre, the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner for British Columbia, and the Commissioner Michael McEvoy for organising the research workshop on data-driven elections. In addition, the author extend a thank you to Mike Miller, the Social Science Research Council, Erika Franklin Fowler, Sarah Anne Ganter, Natali Helberger, Shannon McGregor, Rasmus Kleis Nielsen and especially Dave Karpf and Daniel Kreiss for organising the 2019 International Communication Association post-conference, “The Rise of Platforms” where versions of this paper were presented and received helpful feedback. Sincere thanks to the anonymous reviewers, Frédéric Dubois, Robert Hunt, Tom Hackbarth and especially Colin Bennett for their feedback and suggestions.

References

Adams, K., Barrett, B., Miller, M., & Edick, C. (2019). The Rise of Platforms: Challenges, Tensions, and Critical Questions for Platform Governance [Report]. New York: Social Science Research Council. https://doi.org/10.35650/MD.2.1971.a.08.27.2019

Ananny, M. (2018). Networked press freedom: creating infrastructures for a public right to hear. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Angwin, J., Larson, J., Varner, M., & Kirchner, L. (2017a, August 19). Despite Disavowals, Leading Tech Companies Help Extremist Sites Monetize Hate. ProPublica. Retrieved from https://www.propublica.org/article/leading-tech-companies-help-extremist-sites-monetize-hate

Angwin, J., Larson, J., Varner, M., & Kirchner, L. (2017b, August 19). How We Investigated Technology Companies Supporting Hate Sites. ProPublica. Retrieved from https://www.propublica.org/article/how-we-investigated-technology-companies-supporting-hate-sites

Baldwin-Philippi, J. (2015). Using technology, building democracy: digital campaigning and the construction of citizenship. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190231910.001.0001

Baldwin-Philippi, J. (2017). The Myths of Data-Driven Campaigning. Political Communication, 34(4), 627–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1372999

Bennett, C. (2015). Trends in voter surveillance in western societies: privacy intrusions and democratic implications. Surveillance & Society, 13(3/4), 370–384. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v13i3/4.5373

Bennet, C. J., & Oduro-Marfo, S. (2019, October). Privacy, Voter Surveillance, and Democratic Engagement: Challenges for Data Protection Authorities. 2019 International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners (ICDPPC), Greater Victoria. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20191112101932/https:/icdppc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Privacy-and-International-Democratic-Engagement_finalv2.pdf

Berry, J. M., & Sobieraj, S. (2016). The outrage industry: political opinion media and the new incivility. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bodó, B., Helberger, N., & de Vreese, C. H. (2017). Political micro-targeting: a Manchurian candidate or just a dark horse? Internet Policy Review, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2017.4.776

Braun, J. A., & Eklund, J. L. (2019). Fake News, Real Money: Ad Tech Platforms, Profit-Driven Hoaxes, and the Business of Journalism. Digital Journalism, 7(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1556314

Brown, J. A. (1980). Selling airtime for controversy: NAB self‐regulation and Father Coughlin. Journal of Broadcasting, 24(2), 199–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838158009363979

Busch, T., & Shepherd, T. (2014). Doing well by doing good? Normative tensions underlying Twitter’s corporate social responsibility ethos. Convergence, 20(3), 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856514531533

Cadwalladr, C., & Graham-Harrison, E. (2018, March 17) How Cambridge Analytica Turned Facebook ‘Likes’ into a Lucrative Political Tool. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/mar/17/facebook-cambridge-analytica-kogan-data-algorithm.

Daniels, J. (2009). Cloaked websites: propaganda, cyber-racism and epistemology in the digital era. New Media & Society, 11(5), 659–683. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809105345

Davies, H. (2015, December 11). Ted Cruz campaign using firm that harvested data on millions of unwitting Facebook users. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/dec/11/senator-ted-cruz-president-campaign-facebook-user-data

D’Aprile, S. (2011, September 25). Judge Ends Aristotle Advertising Case. Campaigns & Elections. Retrieved from http://www.campaignsandelections.com/campaign-insider/259782/judge-ends-aristotle-advertising-case.thtml

DeNardis, L. (2012). Hidden Levers of Internet Control. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 720–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.659199

Detrow, S. (2015, December 15). “Bill Wants To Meet You”: Why Political Fundraising Emails Work. All Things Considered, NPR. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2015/12/15/459704216/bill-wants-to-meet-you-why-political-fundraising-emails-work

Drinkwater, R. (2016, October 17). Ezra Levant’s Rebel Media denied UN media accreditation. Macleans. Retrieved from https://www.macleans.ca/news/canada/ezra-levant-rebel-media-denied-un-media/

Duguay, S., Burgess, J., & Suzor, N. (2018). Queer women’s experiences of patchwork platform governance on Tinder, Instagram, and Vine: Convergence. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856518781530

Eatwell, R., & Mudde, C. (Eds.). (2004). Western democracies and the new extreme right challenge. New York: Routledge.

Edmiston, J. (2016, February 17). Alberta NDP says ‘it’s clear we made a mistake’ in banning Ezra Levant’s The Rebel. National Post. Retrieved from https://nationalpost.com/news/politics/alberta-ndps-ban-on-rebel-reporters-to-stay-for-at-least-two-weeks-while-it-reviews-policy-government-says

Elmer, G., Langlois, G., & McKelvey, F. (2012). The Permanent Campaign: New Media, New Politics. New York: Peter Lang.

Ezrahi, Y. (1999). Dewey’s Critique of Democratic Visual Culture and Its Political Implications. In D. Kleinberg-Levin (Ed.), Sites of Vision: The Discursive Construction of Sight in the History of Philosophy (pp. 315–336). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Freelon, D. G. (2010). ReCal: intercoder reliability calculation as a Web service. International Journal of Internet Science, 5(1), 20–33. Retrieved from https://www.ijis.net/ijis5_1/ijis5_1_freelon.pdf

Gillespie, T. (2007). Wired Shut: Copyright and the Shape of Digital Culture. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions That Shape Social Media. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Gilliam, J. (2016, November 17). Choosing to lead. Retrieved from https://nationbuilder.com/choosing_to_lead

Gordon, G., & Goldsbie, J. (2017, August 17). Ex-Rebel Contributor Makes Explosive Claims In YouTube Video. CANADALAND. Retrieved from https://www.canadalandshow.com/caolan-robertson-why-left-rebel/

Gorwa, R. (2019). What is platform governance? Information, Communication & Society, 22(6). https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1573914

Holcombe, M. (2019, January 13). GoFundMe to refund the $20 million USD raised for the border wall. CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/12/us/border-wall-gofundme-refund/index.html

Horowitz, B. (2012, March 8). How to Start a Movement [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.bhorowitz.com/how_to_start_a_movement

Howard, P. N. (2006). New Media Campaigns and the Managed Citizen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Howard, P. N., & Kreiss, D. (2010). Political parties and voter privacy: Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and United States in comparative perspective. First Monday, 15(12). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v15i12.2975

Hunter, A. (2016). “It’s Like Having a Second Full-Time Job”: Crowdfunding, journalism, and labour. Journalism Practice, 10(2), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1123107

Information Commissioner’s Office. (2018). Democracy disrupted? Personal information and political influence. Information Commissioner’s Office. https://ico.org.uk/media/2259369/democracy-disrupted-110718.pdf

Jasanoff, S. (2016). The Ethics of Invention: Technology and the Human Future. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Johnson, D. G., & Mulvey, J. M. (1995). Accountability and computer decision systems. Communications of the ACM, 38(12), 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1145/219663.219682

Johnson, D. W. (2016). Democracy for Hire: A History of American Political Consulting. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190272692.001.0001

Karpf, D. (2016a). Analytic activism: digital listening and the new political strategy. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190266127.001.0001

Karpf, D. (2016b). The partisan technology gap. In E. Gordon & P. Mihailidis (Eds.), Civic media: technology, design, practice (pp. 199–216). Cambridge, MA; London: The MIT Press.

Karpf, D. (2018). The many faces of resistance media. In D. S. Meyer & S. Tarrow (Eds.), The Resistance: The Dawn of the Anti-Trump Opposition Movement (pp. 143–161). New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190886172.003.0008

Karppinen, K. (2013). Uses of democratic theory in media and communication studies. Observatorio, 7(3), 1–17. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.mec.pt/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1646-59542013000300001&lng=en&nrm=iso

Kaye, D. (2019). Speech police: The global struggle to govern the Internet. New York: Columbia Global Reports.

Kim, Y. M., Hsu, J., Neiman, D., Kou, C., Bankston, L., Kim, S. Y., … Raskutti, G. (2018). The Stealth Media? Groups and Targets behind Divisive Issue Campaigns on Facebook. Political Communication, 25(4), 515–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2018.1476425

Kreiss, D. (2016). Prototype politics: technology-intense campaigning and the data of democracy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kreiss, D. (2017). Micro-targeting, the quantified persuasion. Internet Policy Review, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2017.4.774

Kreiss, D., & Jasinski, C. (2016). The Tech Industry Meets Presidential Politics: Explaining the Democratic Party’s Technological Advantage in Electoral Campaigning, 2004–2012. Political Communication, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2015.1121941

Kreiss, D., & Mcgregor, S. C. (2018). Technology Firms Shape Political Communication: The Work of Microsoft, Facebook, Twitter, and Google With Campaigns During the 2016 U.S. Presidential Cycle. Political Communication, 35(2), 155–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1364814

Levy, S. (2002). Crypto: Secrecy and Privacy in the New Code War. London: Penguin.

Liao, S. (2019, March 22). GoFundMe pledges to remove anti-vax campaigns. The Verge. Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/2019/3/22/18277367/gofundme-anti-vax-campaigns-remove-pledge

Marland, A. (2016). Brand Command: Canadian Politics and Democracy in the Age of Message Control. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

McEvoy, M. (2019, February 6). Full Disclosure: Political parties, campaign data, and voter consent [Investigation Report No. P19-01]. Victoria: Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner for British Columbia. Retrieved from https://www.oipc.bc.ca/investigation-reports/2278

McEvoy, M., & Therrien, D. (2019). AggregateIQ Data Services Ltd. [Investigation Report No. P19-03 PIPEDA-035913; p. 29]. Victoria; Gatineua: Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner for British Columbia; Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada. https://www.oipc.bc.ca/investigation-reports/2363

McKelvey, F. (2011). A Programmable Platform? Drupal, Modularity, and the Future of the Web. The Fibreculture Journal, (18), 232–254. Retrieved from http://eighteen.fibreculturejournal.org/2011/10/09/fcj-128-programmable-platform-drupal-modularity-and-the-future-of-the-web/

McKelvey, F., & Piebiak, J. (2018). Porting the political campaign: The NationBuilder platform and the global flows of political technology. New Media & Society, 20(3), 901–918. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816675439

Mosco, V. (2004). The Digital Sublime: Myth, Power, and Cyberspace. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Mouffe, C. (2005). The Return of the Political. New York: Verso.

Myers West, S. (2018). Censored, suspended, shadowbanned: User interpretations of content moderation on social media platforms. New Media & Society, 20(11), 4366–4383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818773059

Nationbuilder. (n.d.). NationBuilder mission and beliefs. NationBuilder. Retrieved January 7, 2020, from https://nationbuilder.com/mission

Nissenbaum, H. (1994). Computing and Accountability. Communications of the ACM, 37(1), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1145/175222.175228

Parsons, C. (2019). The (In)effectiveness of Voluntarily Produced Transparency Reports. Business & Society, 58(1), 103–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650317717957

Phillips, W., & Milner, R. M. (2017). The ambivalent Internet: mischief, oddity, and antagonism online. Malden: Polity.

Porlezza, C., & Splendore, S. (2016). Accountability and Transparency of Entrepreneurial Journalism. Journalism Practice, 10(2), 196–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1124731

Price, M. (2017, August 16). Why We Terminated Daily Stormer [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://blog.cloudflare.com/why-we-terminated-daily-stormer/

Rafter, K. (2016). Introduction: understanding where entrepreneurial journalism fits in. Journalism Practice, 10(2), 140–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1126014

Roberts, S. T. (2019). Behind the screen: content moderation in the shadows of social media. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Rosenblum, N. L. (2008). On the side of the angels: an appreciation of parties and partisanship. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Saminather, N. (2018, August 10). Factbox: Canada’s biggest mass shootings in recent history. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-canada-shooting-factbox-idUSKBN1KV2BO

Stark, L. (2018). Algorithmic psychometrics and the scalable subject. Social Studies of Science, 48(2), 204–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312718772094

Streeter, T. (2011). The Net Effect: Romanticism, Capitalism, and the Internet. New York: New York University Press.

Tusikov, N. (2019). Defunding Hate: PayPal’s Regulation of Hate Groups. Surveillance & Society, 17(1/2), 46–53. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v17i1/2.12908

Westcott, P. (2016, September 23). Targeted Facebook advertising made possible from L2 and Strategic Media 21 [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.l2political.com/blog/2016/09/23/targeted-facebook-advertising-made-possible-from-l2-and-strategic-media-21/

White, H. B. (1961). The Processed Voter and the New Political Science. Social Research, 28(2), 127–150. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40969367

Wong, J. C. (2019, August 23). Document reveals how Facebook downplayed early Cambridge Analytica concerns. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/aug/23/cambridge-analytica-facebook-response-internal-document

Footnotes

1. Promoting new media activism that shames companies for advertising on certain sites, a kind of corporate social responsibility for ad spending (Karpf, 2018).

2. The studies in ongoing reports can be found at: https://citizenlab.ca/2017/02/bittersweet-nso-mexico-spyware/

3. The company provides customers with this data for a fee. Most customers are web technology firms looking for information on who uses their competitors

4. The 2017 annual report re-categorised its usage statistics using active verbs, such as win or engage, rather than industry. As a result, there is no way to determine usage trends over time. The 2017 annual report also includes a curious ‘Other’ category without much detail. The 2018 report abandoned reporting by industry altogether.

5. See Chapter 7 in Phillips and Milner, 2017 for a good summary of the challenge of public debate and moderation.

Add new comment