Can online political targeting be rendered transparent? Prospects for campaign oversight using the Facebook Ad Library

Abstract

A recent policy development has been voluntary self-regulation of internet platforms through the establishment of online ad archives. Since 2018, concern over the potential misuse of platforms has led to calls for reform of online campaign monitoring. In response, Google, Facebook and Twitter made available repositories of political advertisements appearing on their respective platforms. The intended promise was to make the process of political advertising less of a ‘black box’ and render voter targeting more transparent to public review. In this paper, we consider whether the Facebook Ad Library actually improves the capability of regulators and the public to oversee online campaigns. Specifically, we analyse a corpus of ads focusing on Brexit in the lead-up to the European Parliamentary Elections in 2019, to determine whether these data are meaningful compared to reporting of offline campaign activity already required under UK Electoral Commission rules. We examine some 234 individual ad campaigns run during a 14-day period leading up to the election using data collection tools available via the Ad Library interface. A content analysis of individual ads combined with data obtained from the archive about the ad sponsor and demographic reach suggests at a coarse level of detail that micro-targeting has taken place. However, limitations of the Ad Library prevent its effectiveness as an oversight mechanism, as reporting obscures details about overall spend, reach and targeting behaviour, key issues for online political advertising. Based on these findings and the methodological challenge of interrogating the Facebook Ad Library, we reflect on the policy effectiveness of supposedly transparent ad archives as a policy tool.1. Introduction: online political advertising

A core issue in debates about the “platformisation” of the web, is the extent to which users and regulators can adequately interrogate and observe how platforms shape the flow and content of information they carry (Gillespie, 2010; Helmond, 2015; Pasquale, 2015; Schwarz, 2017; Rieder & Hofmann, 2020). Regulators and the public may wish to observe the workings of platforms for a variety of reasons. For example there are concerns that behavioural targeting could be used to populate users’ feed with content reinforcing certain political opinions, or that user profiles could be sold to unscrupulous third parties. The opaqueness of platform operation presents challenges to researchers wishing to better understand the patterns of information consumption online. Platforms are opaque to researchers in a number of important ways: they often lack access to information about how filtering algorithms operate, as this can be a closely-held trade secret. Researchers have also been limited in the extent to which they can reverse-engineer the workings of algorithms without reliable data about the outcomes of algorithmic filtering on a large scale, a problem that has led to development of bottom-up software tools and databases (Edelson et al., 2019; Silva et al., 2020). This paucity of information has led to accusations that internet platforms lack accountability because they deny citizens and users the opportunity to review the rules that govern their operation (McIntyre & Scott, 2008; Perel & Elkin-Koren, 2017; Beraldo et al., 2021).

These problems are particularly acute in the case of political advertising, where scholars have pointed out the increasingly data-driven nature of political campaigns (Howard et al., 2005; Howard, 2006; Hersh & Schaffner, 2013; Nickerson & Rogers, 2014). By all accounts, the use of data in political advertising has only intensified: if exemplar “hypermedia” campaigns (Howard, 2006) of the 1990s employed digital technology to identify and map strategically important groups of swing voters, advancements in predictive targeting of messages over social media have heightened the stakes for data-driven political campaigning in recent years. As Nickerson and Rogers (2014, p. 53) describe, “contemporary political campaigns amass enormous databases on individual citizens and hire data analysts to create models predicting citizens’ behaviours, dispositions, and responses to campaign contact.” With the migration of political advertising onto social networks, the ability to ascertain voter dispositions has further been enhanced. The 2018 Facebook/Cambridge Analytica scandal drew public attention to the possibility that highly-determined groups could wield disproportionate influence by analysing and leveraging data sets obtained from social media apps. The scandal came to prominence in March 2018, when a Channel 4 (2018) sting operation and whistle-blower Christopher Wylie exposed the British political consulting firm for using information from 50 million Facebook profiles in a major breach of data, to shape the outcome of Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 US Presidential Elections (Cadwalladr et al., 2018). The user profiles accessed by Cambridge Analytica contained information such as the age, gender, geographic location, likes, dislikes and social connections of individuals, making it possible to refine statistical models of behaviour further than could be accomplished with coarser data, thereby making political micro-targeting more concerning. One result of the Cambridge Analytica saga was that Facebook restricted access to APIs that had been used by legitimate researchers to study the platform, further centralising the platform’s control over access to data (Bruns, 2018; Beraldo et al., 2021).

In response to public inquiries into their political advertising businesses, Google, Facebook and Twitter each established political ad archives in 2018. These archives were broadly similar in design; they each offered publicly-accessible records of advertisements of a political nature that ran on their platforms, including information about the sponsor of the ad. Facebook defines political ads as those that “reference political figures, political parties, elections, legislation before Parliament and past referenda that are the subject of national debate” (Allan & Leathern, 2018, n.p.). Facebook’s Ad Library was later expanded to include monitoring of additional specific issues including housing, employment and credit opportunities. The Ad Library is proposed by Facebook as a response to public concerns about the potential for manipulation of voters using targeted advertising via the social network, but does it achieve this aim?

There are increasing calls to reform campaign oversight rules to improve the capacity of authorities and the public to observe and regulate online political advertising (Dommett & Power, 2019; Margetts & Dommett, 2020; Neudert, 2020). Campaign monitoring rules, such as those set out by the Electoral Commission in the UK, are informed by traditional concerns related to offline political communication, and lack the required focus and nuance to confront digital political advertising. For example, reporting requirements have not accurately captured spending on digital campaigns because there is no requirement to differentiate between digital and non-digital spending (Dommett & Power, 2019, p. 259). Traditional reporting also does not adequately capture behavioural targeting of messages. Furthermore, we know from research in the USA context that spending on individual Facebook campaigns is small, with much activity below the threshold for reporting set by the Electoral Commission (Edelson et al., 2019). In Europe these issues were raised as part of the European Democracy Action Plan (‘EDAP’) presented by the Commission in December 2020, in particular referring to a “need for more transparency in political advertising” as well as more stringent rules on the use of personal data when targeting political messages (European Commission, 2021, p. 3). Transparency is a key component of proposed reforms: specifically, there are calls for more transparent identification of the source of political messages, more granular detail about spending on online activities, and increased visibility on targeting practices, particularly when combined with data profiling capabilities of online platforms.

Two key questions about the role of ad archives present themselves: does the Facebook Ad Library actually succeed at making transparent the behaviour of political advertisers? And secondly, if there are shortcomings in the Ad Library reporting, how can these be improved to enable meaningful regulatory oversight of political advertisers as laid out in the proposed reforms? This article addresses those two questions by undertaking and reporting on an empirical investigation of political ad campaigns run in the United Kingdom in 2019. The purpose of this investigation is to ascertain the extent to which external publics (like us) can verify the source of messages, understand the spend and reach of campaigns, and identify the presence of targeting behaviour by studying the Ad Library. Since a major concern of observers is the possibility that advertisers can target specific groups of individuals, we investigate whether we can infer specific targeting behaviour from the data presented by the Ad Library which include total reach, demographics of the audience and geographic location of users.

The article is structured as follows: we briefly review the concept of transparency as a mechanism for internet regulation to situate the political ad archive initiatives within broader trajectories of policy-making. We discuss critiques of the transparency approach to regulation, focusing on two main lines of inquiry: first, the ability of transparency initiatives to render information meaningfully visible to publics and second, the socially embedded and complex nature of information sharing within organisations. We then proceed to describe the methods of our empirical investigation of the Facebook Ad Library, before reporting on the results of that study. We find that the Facebook Ad Library affords very limited capability to observe ad targeting behaviour, due to design features which limit the usefulness of data that can be obtained by both the web and API versions of the tool. We conclude by discussing the implications of these findings for the effective regulation of online political advertising.

2. Literature review: transparency, visibility and political action

The political ad archives developed by Facebook, Twitter and Google are continuous with a model of transparent self-governance that has a long history in policy approaches to the internet (Freedman, 2016; Leerssen et al. 2019). The effectiveness of this regulatory model rests on assumptions about the extent to which transparency can, on one hand, effectively render practices visible and on the other hand, be usefully employed by various actors to hold platforms and advertisers to account.

A key debate among scholars of internet policy has been the extent to which self-regulation of online communication services is appropriate to best serve the public interest, and what alternative forms regulation might take (Lessig, 2009). As described by Curran (2016), governance of the internet has proceeded through several phases in which differing forms of regulation have been dominant. During the early development of the internet, scientific norms of openness and information sharing favoured transparency and collaboration between participants. With later commercialisation and market enclosure, limited access to proprietary code became a more dominant feature of web services (Lessig, 2009). While code may have been rendered more opaque compared to open source and collaboratively built alternatives, the regulatory approach still favoured by commercial actors on the internet has has tended towards self-governance and a deferral to technological openness, at least with regards to engineering standards (Curran, 2016). These approaches are consistent with a preference by commercial platforms for laissez-faire market-based regulation as they invite minimal direct interference from the state (Freedman, 2016). One example of quasi-transparent self-regulation is the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), the main standards organisation responsible for development of technical protocols for the web. W3C consists of issue-focused working groups whose membership is open to academic, public sector and commercial representatives, and whose multi-stakeholder decision-making process is often published transparently for public review (Doty & Mulligan, 2013). A predecessor of the political ad archive are transparency reports published by Google and other companies, which summarise actions taken by the companies in response to requests for removal of information, such as copyright takedown notices the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) or government requests made for national security purposes. Publishing this information may help to inform the public of the commercial operators’ compliance with legal obligations but may also serve the function of publicising potential surveillance overreach by government authorities (Losey, 2015). Transparency has also been a core organising principle for hacker subcultures (‘Information wants to be free’) as well as for collaborative projects like Wikipedia and open source software development teams (Anannay & Crawford, 2018, p. 977). Transparency is regularly applied in response to emergence of new online social harms. For example, the UK Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) has produced guidelines encouraging influencers to be more transparent about paid sponsorship in posts and other online advertising (ASA, 2018). Non-broadcast print political advertising in the UK is regulated by the Electoral Commission, which requires that print ads transparently bear the identity of the originating party. Given the existing regulatory focus on transparency, it is expected that online political advertising (and other harms related to opacity of digital platforms) would be approached similarly. Online political ad archives are therefore a logical extension of a regulatory model that has been at various times the dominant approach to internet governance, although it remains to be seen whether national policymakers and publics will view these transparency measures as sufficient to address public concerns.

With recent events highlighting the potential for manipulation of political opinion online, critics have argued that self-regulation fails to provide adequate checks and balances to safeguard the public interest in a democratic online public sphere (Zalnieriute & Milan, 2019; Leerssen et al., 2019). Some legal scholars suggest that efforts to regulate platforms such as Germany’s NetzDG law and similar approaches may have unintended chilling effects on freedom of expression and could lead to unwanted privatised enforcement by entities like Facebook, due to over-enforcement (Coche, 2018; Tworek & Leerssen, 2019). In the UK, the DCMS (2019) report on misinformation urges greater transparency as a key aim of regulation in the realm of political disinformation, stating, “[w]hat does need to change is the enforcement of greater transparency in the digital sphere, to ensure that we know the source of what we are reading, who has paid for it and why the information has been sent to us.” (2019, p. 5). Another key recommendation of the report is that any independent regulator should be granted the power to observe the algorithmic operation of social media companies to gain information from them about data usage practices, as well as the targeting of political messages (2019, p. 96). The effectiveness of mere visibility as a self-regulatory measure may be overstated (Rieder & Hofmann, 2020). Transparency proposals rest on several assumptions about information, organisations and publics which are not fully empirically verified. Drawing on this literature, we address several of the key assumptions about transparency below. These are: the assumption that initiatives render their objects fully visible, and the assumption that publics can and will be able to monitor and act on the information presented.

2.1 Transparency and visibility

When applied to the management of institutions, transparency has often served as a “template or script” for organisational response to public calls for accountability (Edwards, 2020). In the context of political reform, transparency has been deployed as a reaction to problems such as bureaucratic opacity, capricious and unaccountable public authority, corruption and nepotism (Lessig, 2009). Transparency has been associated with feelings of fairness, proof that institutions are working in the public’s best interest, and reduction of hostility and suspicion towards organisations (Fairbanks et al., 2007, p. 29). A core assumption is that these outcomes are a direct result of increased visibility. As Ananny and Crawford argue, “[t]he implicit assumption behind calls for transparency is that seeing a phenomenon creates opportunities and obligations to make it accountable and thus to change it. (2018, p. 974). However, there are potential limits to the effectiveness of transparency in promoting the public interest, related on one hand to the ability of the public to act effectively on the basis of information, and on the other hand to the influence of various actors – including organisations themselves – on the information that is made visible.

2.2 Critiques: transparency as a complex and negotiated social process

Critiques of transparency initiatives have drawn attention to the way that such efforts are embedded in complex social relations. These approaches, “emphasize the complexity of communication and interpretation processes and focus on the complications and paradoxes generated by transparency projects” (Albu & Flyverbom, 2019:281). For example, transparency applied to algorithmic or AI decision-making processes may be incomplete if only one aspect of the process is made visible, since “the challenge is one of relations between data and algorithms, emergent properties of the machine learning process, very likely to be unidentifiable from a review of the code” (Larsson & Heintz, 2020). Fenster (2015) argues for a more nuanced reading of the complex decision-making processes within organisations, and the impact of this complexity on the ability of organisations to maintain secrecy or transparency. Organisations are “unwieldy and incoherent, secretive and yet leaky, settled and ever-changing” (2015, p. 158). So, while “clear and honest” (Fairbanks et al, 2007) communication of objective facts may be a political ideal and guiding aim, actual mechanisms of transparency may fail to be clear or honest in actuality. These goals may be impeded by institutional failings, opposing incentives or power relationships between various actors.

The socially embedded approach is attentive to the possibility that platforms like Facebook may be resistant to transparency, may behave in ways that prevent mechanisms from operating ideally, or may be incapable of implementing transparency measures. Transparency can intentionally occlude, such as when important information is hidden in the ‘detritus’ of a high volume of released information (Ananny & Crawford, 2018, p. 979). Even research conducted with government employees and civil servants has revealed mediating effects that can distort transparency (Anthopoulos et al., 2016). Information is often mediated through professional communicators, with both personal and professional orientations that can shape transparency behaviour (Fairbanks et al., 2007, p. 29). Organisational leadership might withhold sensitive information from other staff, including communicators for reputational or strategic reasons (Fenster, 2015). Indeed, transparency itself may be part of a broader hybrid publicity-transparency strategy designed to increase market share or improve the status of the organisation (Edwards, 2020). In their interviews with government workers, Fairbanks et al. found that respondents feared transparency could be misused or distorted by bad actors to show the organisation in a poor light, causing them to be cautious about releasing information. Recognition of the socially-embedded nature of transparency initiatives alerts us that “organizational decisions, political interests, and conflicting viewpoints may undermine ideals of informational quality and quantity” (Albu & Flyverbom, 2019, p. 286). Additionally, the contested political status of whistleblowers means that those who share protected information, even when acting in the public interest, may be threatened when doing so, despite normative appeals to transparency in other domains (Fenster, 2015).

Even if information is transparently presented to the public, this may not result in effective political action. Often operating within a “marketplace of ideas” paradigm (Coe, 2015), transparency initiatives assume a public that is “ready, willing, and able to act in predictable, informed ways in response to the disclosure of […] information” (Fenster, 2015, p. 152). A surplus of data removed from context, what Lessig (2009b) calls “naked” transparency, can lead to a situation in which a multitude of correlations could be drawn from the same information dump. An oversupply of transparency can result in political paralysis: “We need to see what comparisons the data will enable, and whether those comparisons reveal something real.” (Lessig, 2009b). When information is transparently released to the public domain, there is no guarantee that recipients will behave in rationally-assumed ways. Market-based theories of expression assume that “information is easily discernible and legible; that audiences are competent, involved, and able to comprehend” the information made visible (Ananny & Crawford, 2018, p. 975). Transparency approaches place the burden of responsibility (and costs) on the public to actively seek out and interpret information provided by platforms. An under-resourced public may not be an adequate watchdog to a resource-wealthy organisation, although crowdsourcing and other digital tools may alleviate this. Data journalists work as mediators between transparent datasets and publics, adding a further interpretive lens to the process of turning transparency into political action (Lessig, 2009b). Interpreting transparency initiatives sometimes require expert knowledge or technical skill on the part of observers that disadvantages some groups over others (Albu & Flyverbom, 2019). As Kemper and Kolkman (2019) argue, the complexity of algorithmic systems requires a critical audience to interpret: “An algorithmic model may thus be entirely transparent, but if it is so complex or distributed that even people who work with it daily do not entirely understand it, how can we presuppose out-siders to thoroughly assess its qualities?” (2019, p. 2091). Achieving effective transparency may therefore require investment in quality tools and capacity-building which enable actual public engagement and visibility (Silva et al., 2020; Margetts & Dommett, 2020). Finally, the ability to transparently observe decision-making may encounter the limit of designers’ own understanding of the output of algorithmic or artificially intelligent systems (Ananny & Crawford, 2018, p. 981). The neighbouring concept of “explainability” has been proposed as a normative goal for meaningful oversight of AI for that reason (Larsson & Heintz, 2020). Overall, transparency (where possible) may be understood as a prerequisite, but not a guarantee of effective understanding or meaningful political action.

Studies of transparency across a range of organisations contain lessons for evaluating proposals for internet self-regulation that prioritise transparency. As we describe below, we developed an empirical approach to evaluating the contents of the Facebook political Ad Library. Our aim is to evaluate the extent to which the Ad Library makes the process of political advertising on the platform more transparent to external review, and whether it can meaningfully be used as a source of information to inform policy on online political advertising.

3. Research method

Our research method consisted of live observation of online political advertising during a controversial electoral campaign, using the tools made available by the Facebook Ad Library. We sought to determine what information was possible to collect about online campaigns, and to evaluate whether the Ad Library permits meaningful oversight of campaigns compared to existing reporting requirements such as those laid out by the UK Electoral Commission. Specifically, we investigated whether we could gain insight into the spend by political parties on their online campaigns, the source of political advertising messages and any evidence of targeting based on demographic or other characteristics. To accomplish this, we conducted a computer-aided content analysis of some 234 political ads placed by pro-“Brexit” and pro-“Remain” campaigns on Facebook, between 10th and 24th April, 2019, in advance of the European Parliamentary Elections on 23 May 2019. The units of analysis chosen were individual political advertisements (single posts as defined by Facebook in the Ad Library). The context unit of analysis was the Facebook Ad Library filtered to return results for the UK. For each advertisement, we collected all the data made available from Facebook. These include its demographic reach by age and gender categories, the total advertising spend and its “impressions”, defined as “the number of times that adverts were on-screen” in users’ news feeds (Ads Help Centre, n.d.). The data collection technique permitted us to analyse quantitative aspects of campaign ads and compare these across political parties sponsoring the ads. In addition to identifying the advertiser, the spend and its reach, the Ad Library contains information on demographic reach by age and gender as well as geographical segmentation of the ad audience. These data were collected and analysed with the purpose of addressing the following specific research questions:

- Who is being shown online political ads related to either Pro- or Anti- “Brexit” on Facebook, during the selected time-frame?

- Who are the different political actors and what are they spending for online political advertising related to “Brexit” on Facebook and how easily can they be identified?

- Does the reported pattern of Brexit-related ad impressions in the UK suggest that personalised data-driven targeting has taken place?

- Does the Facebook Ad Library enhance the capabilities of electoral oversight authorities when it comes to online political advertising? If not, what needs to be improved?

3.1 Sampling strategy

Our research focused on political advertisements run on the topic of “Brexit” during the sample period from 10th to 24th April, leading up to the European Parliamentary Elections on 23 May 2019. The Facebook Ad Library at the time of the research was adding new political ads to the archive on a weekly basis, starting from October 2018. The sample size collected over the period of two weeks, reached a size of n=234 political/issue-based advertisements, large enough to permit statistical analysis.

In this study, we focus on political advertisements related to Brexit, due to controversy surrounding Vote Leave’s use of online political advertising during the EU Referendum in 2016 and the possibility that targeting could be observed via the reported reach of ads purchased during our observation period (Cadwalladr et al., 2018). It was widely reported following the referendum of 2016 that the “Leave” campaign had targeted older, rural voters and used nostalgic framing to appeal to those groups (Green 2016). Data collection for our study took place ahead of the European Parliamentary Elections on 23 May 2019 when Brexit was still a contentious political issue. The EU elections were considered crucial for the understanding of the referendum results of 2016, to gauge the extent of polarisation that still existed around the two stances, based on electoral voting for either pro-leave or pro-remain political parties. An analysis of Brexit-related political advertisement and their stances of “Leave” and “Remain” provided an opportunity to conduct live data collection on a politically contentious issue in relation to the insights provided by the Ad Library.

We initially gathered data on ads by searching the UK Ad Library for ads containing the keyword “Brexit” daily during the study period. During this initial phase of data collection we encountered the issue that the number of results returned by the Library fluctuated widely, as new ads were uploaded to the Library in batches and retrospectively, making daily collection unreliable. Consequently, the decision was made to stagger data collection by one week, to allow time for new ads to be uploaded to the platform before collection.

3.2 Other limitations with Ad Library data

When preparing to analyse data obtained from the Facebook Ad Library we immediately encountered challenges. The Ad Library presents aggregated data on the variables of age and geographic location, two important dimensions of political targeting. Age is aggregated into unequal groupings with one large open-ended interval of 65+ years. Location information is aggregated by nation in the UK (e.g. Wales, England, Scotland and Northern Ireland). Total reach is also grouped into broad categories, making statistical comparison of reach more difficult. For example, one of the reported categories for “reach” includes ads that achieved between 10k-50k impressions, significantly obscuring the performance of individual campaigns falling within that broad category. Data aggregation leads to a loss of information, even if it has practical uses such as limiting the size of unwieldy datasets or preventing de-anonymisation for ethical or privacy reasons (Pollet et al. 2015). Interpreting results using aggregated data can lead to making an “ecological fallacy” error which occurs when group attributes are used as a basis for inference about individuals within those groups (Van Bavel et al., 2019). When conducting statistical analysis care must be taken so that relationships detected at the aggregate level are not taken to imply relationships at the individual level (Pollet et al., 2015). While statistical techniques can be applied to estimate individual from grouped data, these techniques may not be applicable to online platforms where we don’t have publicly available dis-aggregated statistics about the user population (Bermúdez, & Blanquero 2016). These features make inference to national populations from social media observations methodologically challenging (Wang et al, 2019).

4. Discussion

The sample of 234 political/issue-based ads collected over a two-week period from the Facebook Ad Library produced a total of at least 9,151,000 impressions and incurred a total spend of at least £99,450, with ‘<£100’ being the most common ad spend category, comprising 65% of the total ads. The £10k-50k range was the second most common category, comprising 32% of the total ads. We coded individual ads based on their stance on Brexit, with 75% of total ads taking a clear stance of either “Leave” or “Remain” (see Table 1). A further 59 ads were coded as neutral, because they did not contain enough information to discern a clear stance on the Brexit issue. For example, one campaign paid for by internet petition hosting company 38 Degrees invited Facebook users to “Map your Brexit: answer a few questions and see what your Brexit plan would look like”. Although on the topic of Brexit and therefore included in our data collection, these ads may have been part of a tangentially-related commercial strategy, for example to harvest voter profiles for third-party use, or to attract politically-active users to external websites regardless of their Brexit preference.

Figure 1 shows how the sample of ads is distributed across the study period, and by different categories of political ad sponsors. We hand-coded all ads using Facebook’s pre-determined category labels and information provided on target pages, resulting in the following categories: Political parties, individual candidates, political organisations (including trade unions and associations), NGOs (including charities) and community groups. A small number of commercial entities and non-candidate individuals were coded as “other”. Community groups had a relatively even spread across the two weeks with less than 10 ads being disseminated each day. There is also a noticeable dip between 12-14 April and 18-20 April, indicating that online political ads were more widely posted during the week, as opposed to the weekends. This could be due to a variety of reasons related to life patterns of targeted users or the working hours of campaigns themselves. Previous research has shown that politicians’ use of social media follows a pattern of intensity during workdays and drops off on evenings and weekends, suggesting that political campaigning may follow professional patterns of working hours (Adi et al., 2014).

While the number of ads disseminated by political issue organisations reduces starkly in the beginning of the two-week period, the number of ads disseminated by political parties and candidates increases towards the end of the two weeks. It is also important to note that 15th April was the last date for political parties to register for standing in the European Parliamentary elections in May 2019. The noticeable rise in the ads disseminated by political parties after 15th April can also be an indicator of the rise in increase online political campaigning for EU elections. However, EU elections weren’t the only upcoming elections attracting advertisements during the two-week period, as UK local elections were also set to take place on 2nd May. So, the increase in political and dissemination by political parties towards the latter half of the duration may have been oriented towards either of the two elections taking place in May. This illustrates a potentially problematic issue for oversight using online ad archives compared to traditional election monitoring mechanisms. While parties and candidates are required to report campaign activities against a specific contest to the UK Electoral Commission, information provided by the Ad Library does not link advertisers to a specific political contest, and in the case of our study sample, may include overlapping campaigns targeting different contests or issues, including at local, regional, national and international scales. The largest officially reported spender in the 2019 European Parliamentary Elections overall was the Brexit Party, which spent a reported £2.6M on its overall campaign (Electoral Commission, 2020). Our findings suggest that the Brexit Party was also the largest spender on Facebook during the Parliamentary Election period (Table 2). However other groups such as “People’s Vote UK” and “38 Degrees” spent significantly on the Brexit issue on Facebook but were not among the top reporting groups in the Electoral Commission data related to the EU Parliamentary Elections.

|

Brexit Stance |

No. Ads |

Impressions |

Estimated Impressions per Ad |

Total Spend (£) |

Estimated cost per thousand (CPM) (£) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Neutral |

59 |

1293500 |

21924 |

6400 |

4.95 |

|

Leave |

43 |

3292500 |

76570 |

45750 |

13.89 |

|

Remain |

132 |

4565000 |

34583 |

47300 |

10.36 |

|

Total |

234 |

9151000 |

39107 |

99450 |

10.86 |

|

Advertiser |

Estimated Ad Spend (£) |

|---|---|

|

The Brexit Party |

43500 |

|

Liberal Democrats |

27950 |

|

People's Vote UK |

9900 |

|

Best for Britain |

6400 |

|

38 Degrees |

5950 |

|

Conservatives |

900 |

|

Loving Europe 2 |

750 |

|

I Love EU |

450 |

|

Scottish Environment |

450 |

|

Best for Doncaster |

300 |

Although the metric of ad impressions does not provide the number of unique views per ad, making it a rather a skewed measurement of the actual potential reach of a particular ad, it is the most widely used indicator of cost-effectiveness of an online advertising campaign. Facebook, in particular, uses a CPM (cost-per-1,000 impressions) metric (Ads Help Centre, n.d.). Our data show that “Leave” campaign ads incurred the highest CPM of £13.89, while the lowest CPM (£4.95) was observed for neutral ads with no discernible political stance. These data suggest, as per observations by Edelson et al. (2019) that it may be more costly to reach specifically targeted audiences with political messages on Facebook, or that the targeting methods used vary across political actors and yield different results in terms of impressions and engagement.

While limited by the reporting of aggregate data in ranges for total spend and impressions, the Facebook Ad Library data provides some insight into the online campaign activity that is not currently available from offline reporting. The UK Electoral Commission oversees political campaigns including those for the 2019 EU Parliamentary elections and sets spending limits for campaigns (Electoral Commission, n.d. a). These limits apply during the “regulatory period” of 4 months in advance of the election. The limits vary between Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, but for England they depend on the number of MEPs returned for a given region. Parties and non-party campaigners must report expenses related to a range of activities, which include items like unsolicited material sent to voters, advertising using lists (online or offline), market research and rallies or events (Electoral Commission, n.d. a, p. 12). The headline activities, conceived in a pre-digital world, do not provide meaningful information about the intensity of resources devoted to online activities in any of the categories which may include a range of media types. For example, since Facebook does not provide information about how ads were targeted, it is impossible to know whether a given online ad was aimed at a predetermined list of voters or was unsolicited. Furthermore, advertising and reporting limits established in the print world may not adequately correspond to the influence possible with targeted online advertising at a significantly lower cost. The Electoral Commission threshold for reporting in England is £20,000. In the Facebook context it is possible that smaller advertisers could reach a significant digital audience with political messages without having to report that activity. We found a preponderance of very small campaigns (<£100) in our sample, indicating the possible presence of political actors not picked up by traditional monitoring rules.

4.1 Who is paying for online political advertisements related to ‘Brexit’ on Facebook?

Our analysis of Ad sponsors reveals that a wide range of different political actors made use of online advertising on Facebook. The main actors that made use of political advertising related to “Brexit” on Facebook’s platform, for the two-week time period, were political parties, political issue organisations, non-government organisations, citizen community groups and political candidates. The categories used to compare ad sponsors were derived from assigned categories provided on the advertisers’ Facebook pages as well as by further checking sponsor websites to confirm the categories. These categories, while coarse, align with expected political actors that undertake offline methods of political advertising, as indicated by previous research (ICO, 2018a), but with some exceptions, discussed below. This research encountered some for-profit businesses and other non-candidate individuals that did not have a direct relationship to the Parliamentary elections, and were grouped as “others”. Edelson et al. (2019) also observed in their study of online political advertising in the USA that the Facebook Ad Archive contained “a wider breadth of political ad types and sponsors,” than typically monitored, including commercial participants that created politically-charged ads as well as organisations with no clear intent. In the 2016 Presidential election in the USA, these included a Russian company named the Internet Research Agency (IRA) (Ribeiro et al. 2019; Silva et. al., 2020).

Figure 2 shows the dominance of political parties accounting for the largest amount of Facebook ad impressions (60.2%) and the highest ad spend (72.9%) as compared to the rest of the political advertisers. In the case of political organisations and non-government organisations, one can also see that their impressions are higher in the proportion to their ad spends (Figures 2 & 3), and in the case of political parties, it is the opposite. As discussed above, the CPM rates for politically-targeted messages were higher than for politically neutral messages, as they are for political parties compared to NGOs and other organisations. The higher CPM rates suggest the presence of targeting, as it may cost more to target hard-to-reach demographics and audiences in more contested markets (Dommett & Power, 2019, p. 263). A lack of visibility into the way that Facebook and other online platforms price their ads means there is potential for algorithmic bias, which may unintentionally occur if advertising practices or target audiences are different between political actors, resulting in higher pricing. Overall, the higher CPM rates for political party messages suggests that this type of advertising is commercially attractive to online platforms.

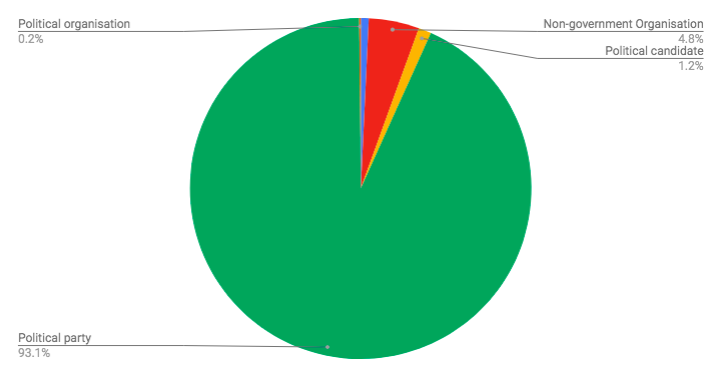

We further examined whether the type of political sponsors differed by Brexit stance. According to the results shown in Figure 4, 93.1% of the total impressions created by “Leave” Ads were from Political Parties, as opposed to 53.5% in the case of “Remain” ads. In the case of “Remain” ads, the impressions were more evenly distributed amongst political parties and political organisations, indicating the prevalence of both party and non-party organisations campaigning for “Remain”, as opposed to the party-based dominance visible within the “Leave” ads (Figure 5). However, an overall analysis clearly indicates that political parties are the most prevalent category of political sponsors for online Facebook ads related to Brexit, over the course of two weeks that are assessed in this research.

The Brexit Party, a new pro-Leave party led by Nigel Farage, was the top advertiser by impressions and ad spend, followed closely by Liberal Democrats, a pro-Remain party (See Table 2). Lower spend on the Brexit issue by Labour and the Conservatives is notable. Online ad platforms like Facebook may provide smaller political parties with an opportunity to conduct targeted communications on specific issues at lower cost, making online political advertising a more significant form of campaigning for these organisations.

4.2 Content of online political advertising related to Brexit: what is being shown?

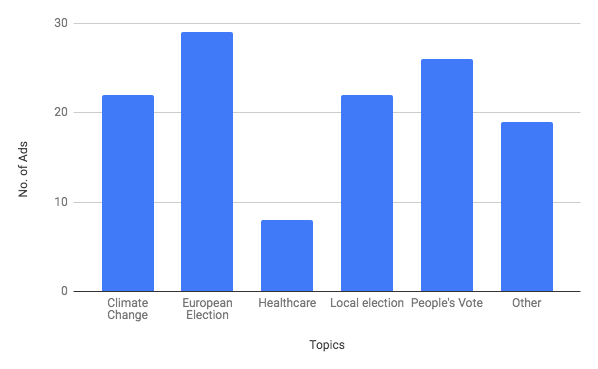

Some 80% of the ads contained in our sample contained simple images with text elements. A further 10% contained video content while 10% were “carousel” style ads. The ads contained in our sample displayed a range of different imagery and used a range of rhetorical techniques (for one example see Figure 7). They also drifted away from Brexit into other related political topics as well as other political contests happening at the national and European scale (see Figure 6 below).

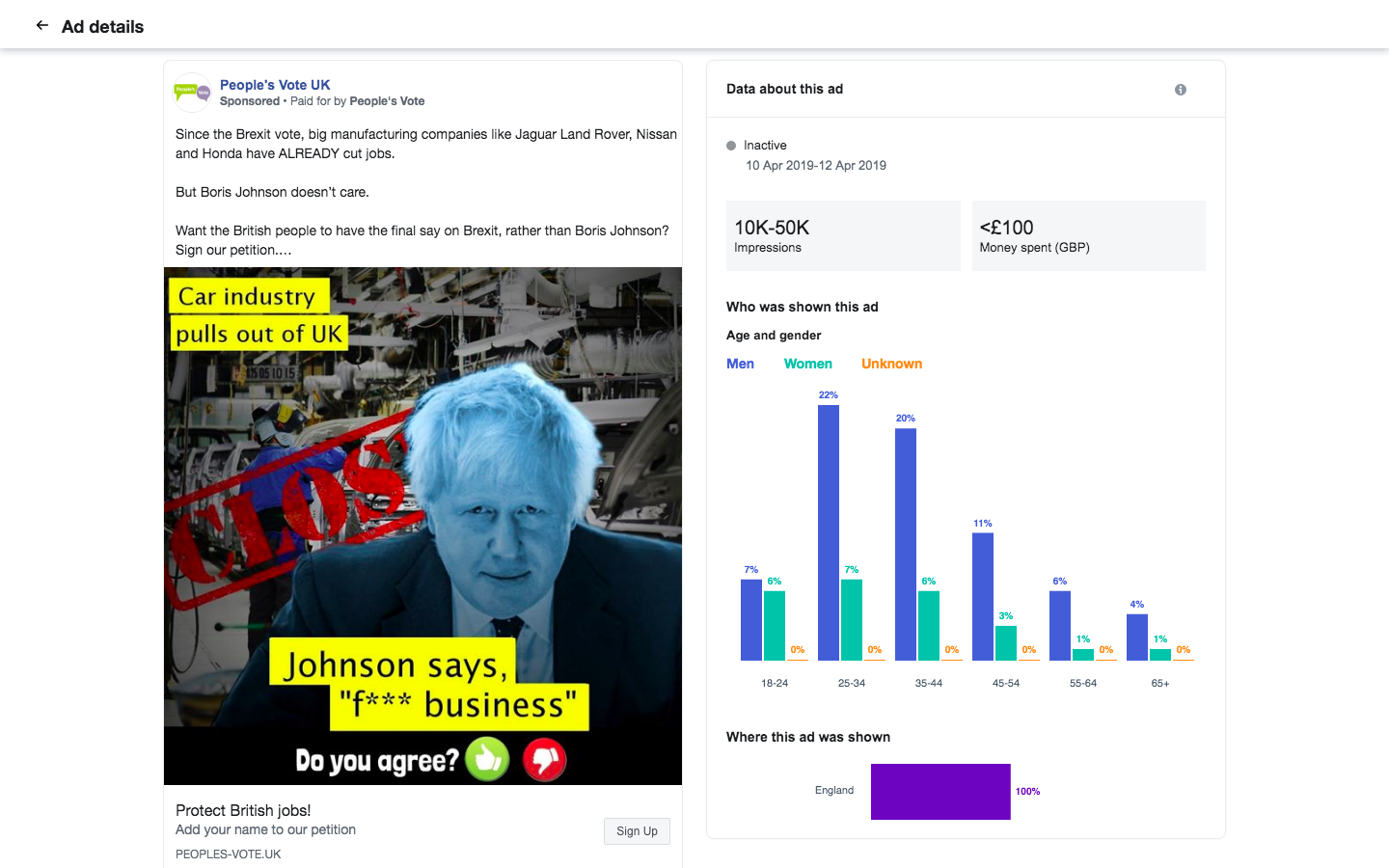

Compared to traditional political advertising in print or television, some of the content observed in the sample contained extreme or vernacular language that made it harder to identify the content as a political advertisement. For example, one “Leave” ad used a vernacular portmanteau to paint the supporters of remaining in the EU as “moaners”: “Remoan are anti-democratic, like the evil empire they serve,”. Suggesting the international, cross-border nature of online political messages, another ad implored voters to “Make Britain Great Again”. Some ads consisted of images of pro-Leave political candidates painted as clowns. Ads from “People’s Vote UK”, a pro-remain political organisation, ran multiple ad campaigns with attack imagery. These portrayed Boris Johnson, using a “Saatchi and Saatchi” aesthetic style of political advertising, reminiscent of the “New Labour, New Danger” campaign in the 1997 General Election (Scammell and Langer, 2006). One issue raised by the UK Electoral Commission and also apparent in our study is that ads may not have a clear target in terms of a specific electoral race or referendum in the UK, and are not labelled as such by Facebook. Consequently, campaign spending monitoring may be difficult, as ads can serve multiple purposes and reach different electorates simultaneously. The current system of ad spend monitoring requires that campaigns report their invoices against a specifically identifiable political contest within a predetermined regulatory time period to the monitoring body (Electoral Commission, 2021), but this may inadequately reflect the continuous and dynamic online political advertising environment that is emerging..

The majority of the ads analysed (70%) included a call to action. The most common call to actions were “Sign Up” and “Sign Petition”, both of which consisted of links to the advertiser’s website, asking the user to provide their personal information. While the user may not wish to sign up, other calls to action also included “liking” the advertiser's page, or to opt-in to receive future communications from the advertiser. Another call to action included “Take the quiz”, which was used only by one advertiser, 38 Degrees, to persuade users to take the platform’s quiz on Brexit, which appeared designed to obtain precise Brexit-related user information and personal data for future use.

4.3 Who is being shown online political advertisements related to Brexit on Facebook?

We next examined the corpus of ads to determine whether it was possible to detect evidence of targeting from the data made available about campaigns in the Facebook Ad Library. Demographic profiling has become a common practice for online advertisers, offered through dynamic advertising features such as “Lookalike” and Custom Audiences on Facebook which match ads to individuals based on certain selected criteria such as age, gender, interests or behaviour (Faizullabhoy & Korolova, 2018). Facebook provides very limited information about targeting in its Ad Library. It does not reveal whether advertisers have used any selective criteria to target an Ad, only general information about the gender, age and geographic location of people who were shown the ad. The Ad Library does not even reveal, at a meta level, whether any targeting has taken place, for example whether the advertiser used an uploaded list or a Lookalike audience. In terms of political messaging, scholarship in political communication has identified that at the most coarse level, age and gender are correlated with different voting preferences in previous political contests (Butler and Stokes, 1974; Krosnick & Alwin, 1989; Norris, 1996). It may then be expected to see political campaigners on Facebook using at least these characteristics of age and gender to target recipients based on their anticipated preferences.

Figure 8 shows the demographic (gender and age) breakdown in number of impressions. A pattern of difference according to both gender and age, in relation to political messages from both “Leave” and “Remain”, is apparent. “Remain” ads were shown to younger, female Facebook users. Contrastingly, “Leave” ads skewed towards older demographics (45+ years), with an inclination towards male audiences. Brexit polling showed that younger voters and females were more likely to support the “Remain” position (Ipsos 2016). Our findings suggest that if Leave/Remain ads were targeted, the strategy may reflect a goal of appealing to existing political beliefs rather than attempting to change existing political preferences. However, since the Ad Library does not reveal what targeting criteria ad purchasers selected when building their campaigns, we cannot be certain whether the observed pattern reflects targeting intention on the part of advertisers or perhaps Facebook’s own internal filtering of accounts more likely to respond positively to the ads being shown. Another possibility is that some other, unobserved variable chosen by ad purchasers when designing their campaigns is also correlated with age and gender characteristics of targeted users, confounding the results.

Finally, we evaluated whether it was possible to infer geographic targeting from the observed pattern of impressions. While geographic-level data are coarse, the Ad Library shows national-level populations being targeted within the countries of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Figure 9 shows that 87.9% of the total impressions were located within England, indicating an England-centric geographical spread of Brexit ads shown on Facebook. In the 2011 census, England made up 84% of the total population of the UK. Similarly to age and gender demographics, the geographic location is reported in the Ad Library as a percentage, rather than absolute number so the average percentages of each of the 4 countries were used to produce the chart in Figure 9. While analysing ads based on geographical spread, we observed that the Ad Library data for some of the other countries, like the US and India, contains more detailed insights about geolocation than the UK. In both of those countries, the impression percentages are broken down at the state level, allowing slightly higher resolution geographic analysis. However, as with the above discussion, We don’t know from the data made available by Facebook whether geographic location was a factor in targeting specific ads about Brexit in the 2019 EU Parliamentary elections.

4.4 Limitations of the Facebook Ad Library

From the perspective of political communication research, the Ad Library does provide some useful data to researchers and public observers about the ads displayed on the platform, and helpfully collects them in one place. The Library provides an indication of the identity of the organisation that bought a particular ad (although not a full address or identification number), the time period the ad was shown and a rough estimate of the total ad spend and reach. These data do not extend beyond what is currently collected by the UK Electoral Commission, where the focus has been on policing the total amount spent on advertising by political candidates and organisations in an election. The Facebook Ad Library does capture smaller political advertisers who might not meet the threshold for reporting to the Electoral Commission. The usefulness of the Library is significantly limited by reporting only ranges rather than absolute numbers for money spent and number of people reached. It is likely that these figures are obscured because of concern by Facebook that they would reveal information about how the company prices their ads. Exact CPM rates could be worked out and compared across different ad buyers if exact numbers were reported. As previously discussed, the aggregation of data reported by the Ad Library in unequal intervals poses challenges for statistical analysis.

Perhaps more importantly, the Ad Library offers no additional insight about the potential for targeting, beyond broad reporting on impressions by age, gender and wide geographic location. This is disappointing considering the level of detail available to Facebook both from its Ad Builder tool, used by ad buyers to target specific demographics beyond basic categories like age and gender, and from Facebook’s knowledge about the behaviour of users that leads to them being shown particular ads. A platform like Facebook that has invested heavily in user experience on its social platform could be expected to be able to provide the same level of sophistication in its ad archive, and doing so would considerably improve the prospects for monitoring online campaigns.

Another key limitation of the Facebook Ad Library is the lack of context surrounding online political advertising. Users do not view these ads in isolation, devoid of any context. The digital ads form a key part of an individual's personalised News Feed on Facebook, which Adshead et al. (2019, p. 25) describe as being “integrated into the surrounding content in a non-interruptive way, following the form and function of the user experience in which it is placed”. “In-feed” advertising then becomes a way to contextualise promotional content amidst the network’s cultural artefacts, carefully combining “values of attention, popularity, and connectivity” (van Dijck, 2013, p. 62). Information that would be of importance to researchers of political micro-targeting include: the ads that a user was shown previously and subsequently, the level of engagement and attention given by a user to a specific ad, and any other prior behaviours of relevance, such as following a related political party or issue page on Facebook. Research methods incorporating the feed and user behaviour into unpacking the black box are therefore likely to be more instructive about the overall process of political targeting, although also potentially more laborious (see for example Edelson et al., 2019; Silva et al., 2020; Beraldo et al., 2021).

Overall, we find that the Ad Library can provide an overview of advertising behaviour by a range of political participants around a defined political issue. It does not currently function adequately as a watchdog tool beyond providing a general estimate of total campaign spend, and even there falls short of traditional reporting procedures due to lack of precision in data reported.

5. Conclusion

Transparency alone is not sufficient to provide meaningful oversight of online political advertising. While political ad archives such as the Facebook Ad Library promise a new level of transparency into the campaign process, the initiative falls short of delivering the information required for effective monitoring. Specifically, the issues of overall spend, the precise source of political messages, and presence of targeting remain inaccessible to oversight using the current tool. In order to be effective, transparency initiatives need to meaningfully embed the needs of external stakeholders, including electoral monitoring authorities, into their systems. We have outlined in this paper why it essential for certain key information to be included in the design, to better serve the interest of protecting fair and democratic elections.

Despite its present shortcomings, the transparency model continues to inform self-regulatory initiatives and frameworks. Technology companies have expressed preference for self-regulatory mechanisms over government intervention, and have deployed these claims effectively to avoid direct regulatory involvement. Critiques of the transparency approach cast doubt on the effectiveness of such mechanisms to serve the public interest. Concerns focus on: the capacity of citizens to seek out and interpret information, structural imbalances in power between organisations and observers, bureaucratic complexity and recalcitrance within businesses, and the presence of financial incentives working against meaningful transparency. Questions remain, therefore, about the prospects for transparency mechanisms like the Ad Library to overcome these deficiencies. To what extent could transparency be enhanced to enable citizens to meaningfully understand how political campaign messages circulate on social media?

Using the current tool, we found patterns suggestive of targeting in the display of ads relating to Brexit shown in the United Kingdom. The patterns are most clearly visible along the dimensions of age and gender. Coarseness in the data provided by Facebook prohibits deeper understanding of targeting that may take place according to geographic location or other demographic/interest-based characteristics. The presence of more fine-grained categories in Facebook’s Ad Builder tool suggests that Facebook possesses more nuanced data but has chosen not to include them in the Ad Library. Future research might make use of the Ad-builder tool by Facebook to simulate campaigns that use targeting options, perhaps to reverse-engineer the targeting process and gain deeper insight into how the platform’s algorithms and advertising business interact.

New regulatory approaches are needed to more meaningfully interrogate the behaviour of online political advertising, including micro-targeting. There are calls to require platforms to provide more granular detail about the mechanisms of targeting users with political ads, through a commitment to high-quality research data repositories (Bruns, 2018). Leerssen et al. (2019) suggest including an equivalent level of information to the public as available to the actual ad buyer, including information about the groups they targeted as well as the groups actually shown the ad by the platform. This would assist fuller monitoring of both political ad buyers and the algorithmic process that populate users’ feeds and intermediate between advertising content and users. However, as discussed, there are numerous and plausible reasons why full transparency and public oversight may remain elusive. In the case of Facebook, the incentives working against full transparency are likely a desire for secrecy about the precise functioning of the recommendation feed, and secrecy around the advertising rates charged to different groups on political issues.

A lack of clear regulation of the online political landscape may enable political ads prohibited from print and broadcast mediums to make their way onto social media platforms, avoiding formal rules. The existing regulatory frameworks that govern online political advertising practices in the UK are rather fragmented, with different bodies like the Advertising Standards Authority, the Information Commissioner’s Office and Electoral Commission governing different aspects of the process, without a single framework for monitoring online political advertising (Electoral Commission, 2021). The multimedia nature of online ad content can also pose new challenges to the way in which political advertising has been traditionally regulated, through the intermediation of user signals such as “likes” and “shares”, among other digital affordances.

At stake in the debate about the appropriate regulation of political advertising is society’s comfort with the practice of political targeting more generally. Electoral authorities and publics need visibility into the political targeting of messages on social media in order to determine what practices are acceptable in fair and democratic elections. Here, we have shown that issue-based campaigns reached specific groups on Facebook based on their age and gender. These findings alone raise questions about the intentions of political advertisers and the robustness of traditional models of public deliberation and political choice. Of further concern, Facebook’s ad buying tool offers many ways to discriminate and select between potential audiences that are not visible to researchers via the Ad Library. Gaining a limited view inside of the black box may not be meaningful from a policy perspective; we must also be able to understand and act on the insights contained within.

References

Adi, A., Erickson, K., & Lilleker, D. G. (2014). Elite tweets: Analyzing the Twitter communication patterns of Labour Party peers in the House of Lords. Policy & Internet, 6(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/1944-2866.POI350

Ads Help Centre. (XXXX). Impressions | Facebook Ads Help Centre [[Online]]. https://www.facebook.com/business/help/675615482516035

Adshead, S., Forsyth, G., Wood, S., & Wilkinson, L. (2019). Online advertising in the UK (D.C.M.S. Committee) [Report]. Plum Consulting. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/777996/Plum_DCMS_Online_Advertising_in_the_UK.pdf

Albu, O. B., & Flyverbom, M. (2019). Organizational transparency: Conceptualizations, conditions, and consequences. Business & Society, 58(2), 268–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650316659851

Allan, R., & Leathern, R. (2018). Increasing transparency for ads related to politics in the UK. Facebook Newsroom. https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2018/10/increasing-transparency-uk/

Ananny, M., & Crawford, K. (2018). Seeing without knowing: Limitations of the transparency ideal and its application to algorithmic accountability. New Media & Society, 20(3), 973–989. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816676645

Andersson Schwarz, J. (2017). Platform logic: An interdisciplinary approach to the platform-based economy. Policy & Internet, 9(4), 374–394. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.159

Anthopoulos, L., Reddick, C. G., Giannakidou, I., & Mavridis, N. (2016). Why e-government projects fail? An analysis of the Healthcare.gov website. Government Information Quarterly, 33(1), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2015.07.003

Beraldo, D., Milan, S., Agosti, C., Sotic, B. N., Vliegenthart, R., Kruikemeier, S., & Votta, F. (2021). Political advertising exposed: Tracking Facebook ads in the 2021 Dutch elections. Internet Policy Review. https://policyreview.info/articles/news/political-advertising-exposed-tracking-facebook-ads-2021-dutch-elections/1543

Bermúdez, S., & Blanquero, R. (2016). Optimization models for degrouping population data. Population Studies, 70(2), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2016.1158853

Bruns, A. (2018). Facebook shuts the gate after the horse has bolted, and hurts real research in the process. Internet Policy Review. https://policyreview.info/articles/news/facebook-shuts-gate-after-horse-has-bolted-and-hurts-real-research-process/786

Butler, D., & Stokes, D. (1974). Political Change in Britain: The Evolution of Electoral Choice. Macmillan.

Cadwalladr, C., Graham-Harrison, E., & Townsend, M. (2018). Revealed: Brexit insider claims Vote Leave team may have breached spending limits. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/mar/24/brexit-whistleblower-cambridge-analytica-beleave-vote-leave-shahmir-sanni

Channel 4 News Investigations Team. (2018). Exposed: Undercover secrets of Trump’s data firm [Online]. Channel 4 News. https://www.channel4.com/news/exposed-undercover-secrets-of-donald-trump-data-firm-cambridge-analytica

Coche, E. (2018). Privatised enforcement and the right to freedom of expression in a world confronted with terrorism propaganda online. Internet Policy Review, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2018.4.1382

Coe, P. (2015). A seismic shift? An evaluation of the impact of new media on perceptions of freedom of expression and privacy. Amsterdam Privacy Conference. https://publications.aston.ac.uk/id/eprint/28401/1/Impact_of_new_media_on_perceptions_of_freedom_of_expression_and_privacy.pdf

Curran, J. (2016). Rethinking internet history. In J. Curran, N. Fenton, & D. Freedman (Eds.), Misunderstanding the Internet (pp. 117–144). Routledge.

D.C.M.S. Committee. (2019). Disinformation and ‘fake news’: Final Report (Report No. 8). House of Commons. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmcumeds/1791/1791.pdf

Dommett, K., & Power, S. (2019). The political economy of Facebook advertising: Election spending, regulation and targeting online. The Political Quarterly, 90(2), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12687

Doty, N., & Mulligan, D. K. (2013). Internet multistakeholder processes and techno-policy standards: Initial reflections on privacy at the World Wide Web Consortium. J. on Telecomm. & High Tech. L, 11, 135.

Edelson, L., Sakhuja, S., Dey, R., & McCoy, D. (2019). An analysis of United States online political advertising transparency. https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.04385

Edwards, L. (2020). Transparency, publicity, democracy, and markets: Inhabiting tensions through hybridity. American Behavioral Scientist, 64(11), 1545–1564. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764220945350

Electoral Commission. (2020, April 3). Party spending over £250,000 at the 2019 European Parliamentary elections. https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/media-centre/party-spending-over-ps250000-european-parliamentary-elections-published

Electoral Commission. (2021). Digital campaigning – increasing transparency for voters [Report]. Electoral Commission. https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/who-we-are-and-what-we-do/changing-electoral-law/transparent-digital-campaigning/report-digital-campaigning-increasing-transparency-voters

Electoral Commission. (XXXXa). European Parliamentary elections 2019 (GB and NI): Non-party campaigners. https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/sites/default/files/pdf_file/European-Parliament-Candidates-NI-2019.pdf

Electoral Commission. (XXXXb). European Parliamentary elections 2019: Political parties (GB). The Electoral Commission. https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/sites/default/files/pdf_file/European-Parliament-Political-Parties-GB-2019.pdf.pdf

European Commission. (2021). Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the transparency and targeting of political advertising. https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12826-Political-advertising-improving-transparency_en

Fairbanks, J., Plowman, K. D., & Rawlins, B. L. (2007). Transparency in government communication. Journal of Public Affairs: An International Journal, 7(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.245

Faizullabhoy, I., & Korolova, A. (2018). Facebook’s advertising platform: New attack vectors and the need for interventions. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1803.10099

Fenster, M. (2015). Transparency in search of a theory. European Journal of Social Theory, 18(2), 150–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431014555257

Freedman, D. (2016). Outsourcing internet regulation. In J. Curran, N. Fenton, & D. Freedman (Eds.), Misunderstanding the Internet (pp. 95–120). Routledge.

Gillespie, T. (2010). The politics of ‘platforms.’ New Media & Society, 12(3), 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809342738

Green, E. (2016, August 30). How Brexiteers appealed to voters’ nostalgia. British Politics and Policy at LSE. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/how-brexiteers-appealed-to-voters-nostalgia/

Helmond, A. (2015). The platformization of the Web: Making web data platform ready. Social Media and Society, 1(2), 205630511560308. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115603080

Hersh, E. D., & Schaffner, B. F. (2013). Targeted campaign appeals and the value of ambiguity. The Journal of Politics, 75(2), 520–534. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381613000182

Howard, P. N. (2005). New Media Campaigns and the Managed Citizen (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511615986

Howard, P. N., Carr, J. N., & Milstein, T. J. (2002). Digital technology and the market for political surveillance. Surveillance & Society, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v3i1.3320

Information Commissioner’s Office. (2018). Democracy disrupted? Personal information and political influence. The Electoral Commission.

Kemper, J., & Kolkman, D. (2019). Transparent to whom? No algorithmic accountability without a critical audience. Information, Communication & Society, 22(14), 2081–2096. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1477967

Kreiss, D. (2016). Prototype Politics: Technology-Intensive Campaigning and the Data of Democracy. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199350247.001.0001

Krosnick, J. A., & Alwin, D. F. (1989). Aging and susceptibility to attitude change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 416–425. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.3.416

Larsson, S., & Heintz, F. (2020). Transparency in artificial intelligence. Internet Policy Review, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.2.1469

Leerssen, P., Ausloos, J., Zarouali, B., Helberger, N., & de Vreese, C. H. (2019). Platform ad archives: Promises and pitfalls. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1421

Lessig, L. (2006). Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace Version 2.0 (Version 2.0). Basic Books.

Lessig, L. (2009). Against transparency: The perils of openness in government. The New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/70097/against-transparency

Losey, J. (2015). Surveillance of communications: A legitimization crisis and the need for transparency. International Journal of Communication, 9, 3450–3459.

Margetts, H., & Dommett, K. (2020). Conclusion: Four recommendations to improve digital electoral oversight in the UK. The Political Quarterly, 91(4), 745–750. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12887

McIntyre, T. J., & Scott, C. (2008). Internet Filtering: Rhetoric, Legitimacy, Accountability and Responsibility. In R. Brownsword & K. Yeung (Eds.), Regulating Tech: Legal Futures, Regulatory Frames and Technological Fixes. Hart Publishing.

Milan, S., & Agosti, C. (2019). Personalisation algorithms and elections: Breaking free of the filter bubble. Internet Policy Review. https://policyreview.info/articles/news/personalisation-algorithms-and-elections-breaking-free-filter-bubble/138

Mill, J. S. (1892). On liberty. Longman, Roberts & Green.

Neudert, L. (2020). Hurdles and pathways to regulatory innovation in digital political campaigning. The Political Quarterly, 91(4), 713–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12915

Nickerson, D. W., & Rogers, T. (2014). Political campaigns and big data. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(2), 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.28.2.51

Norris, P. (1996). Mobilising the “Women’s Vote”: The Gender-Generation Gap in Voting Behaviour. Parliamentary Affairs, 49(2), 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pa.a028683

Perel, M., & Elkin-Koren, N. (2016). Accountability in algorithmic copyright enforcement. Stanford Technology Law Review, 19, 473–533.

Pollet, T. V., Stulp, G., Henzi, S. P., & Barrett, L. (2015). Taking the aggravation out of data aggregation: A conceptual guide to dealing with statistical issues related to the pooling of individual-level observational data. American Journal of Primatology, 77(7), 727–740. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.22405

Ribeiro, F. N., Saha, K., Babaei, M., Henrique, L., Messias, J., Benevenuto, F., & Redmiles, E. M. (2019). On microtargeting socially divisive ads: A case study of russia-linked ad campaigns on facebook. Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1145/3287560.3287580

Rieder, B., & Hofmann, J. (2020). Towards platform observability. Internet Policy Review, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.4.1535

Scammell, M., & Langer, I. (2006). Political advertising in the United Kingdom. In L. Kaid & C. Holtz-Bacha (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political advertising. Sage Publications.

Silva, M., Santos de Oliveira, L., Andreou, A., Olma Vaz de Melo, P. G., Goga, O., & Benevenuto, F. (2020). Facebook Ads Monitor: An Independent Auditing System for Political Ads on Facebook. Proceedings of the World Wide Web ‘20 Conference. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2001.10581.pdf

Tworek, H., & Leerssen, P. (2019). An Analysis of Germany’s NetzDG Law (Transatlantic High Level Working Group on Content Moderation Online and Freedom of Expression) [Working Paper]. https://www.ivir.nl/publicaties/download/NetzDG_Tworek_Leerssen_April_2019.pdf

Van Bavel, J. J., Rathje, S., Harris, E., Robertson, C., & Sternisko, A. (2021). How social media shapes polarization. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(11), 913–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.07.013

van Dijck, J. (2013). The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199970773.001.0001

Wang, Z., Hale, S. A., Adelani, D., Grabowicz, P. A., Hartmann, T., Flöck, F., & Jurgens, D. (2019). Demographic inference and representative population estimates from multilingual social media data. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1905.05961

Zalnieriute, M., & Milan, S. (2019). Internet architecture and human rights: Beyond the human rights gap. Policy & Internet, 11(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.200

Add new comment