Towards a holistic perspective on personal data and the data-driven election paradigm

This commentary is part of Data-driven elections, a special issue of Internet Policy Review guest-edited by Colin J. Bennett and David Lyon.

Politics is an art and not a science, and what is required for its mastery is not the rationality of the engineer but the wisdom and the moral strength of the statesman. - Hans Morgenthau, Scientific Man versus Power Politics

Voters, industry representatives, and lawmakers – and not infrequently, journalists and academics as well – have asked one question more than any other when presented with evidence of how personal data is changing modern-day politicking: “Does it work?” As my colleagues and I have detailed in our report, Personal Data: Political Persuasion, the convergence of politics and commercial data brokering has transformed personal data into a political asset, a means for political intelligence, and an instrument for political influence. The practices we document are varied and global: an official campaign app requesting camera and microphone permissions in India, experimentation to select slogans designed to trigger emotional responses from Brexit voters, a robocalling-driven voter suppression campaign in Canada, attack ads used to control voters’ first impressions on search engines in Kenya, and many more.

Asking “Does it work?” is understandable for many reasons, including to address any real or perceived damage to the integrity of an election, to observe shifts in attitudes or voting behaviour, or perhaps to ascertain and harness the democratic benefits of the technology in question. However, discourse fixated on the efficacy of data-intensive tools is fraught with abstraction and reflects a shortsighted appreciation for the full political implications of data-driven elections.

“Does it work?”

The question “Does it work?” is very difficult to answer with any degree of confidence regardless of the technology in question: personality profiling of voters to influence votes, natural language processing applied to the Twitter pipeline to glean information about voters’ political leanings, political ads delivered in geofences, or a myriad of others.

First, the question is too general with respect to the details it glosses over. The technologies themselves are a heterogenous mix, and their real-world implementations are manifold. Furthermore, questions of efficacy are often divorced of context, and a technology’s usefulness to a campaign very likely depends on the sociopolitical context in which it lives. Finally, the question of effectiveness continues to be studied extensively. Predictably, the conclusions of peer-reviewed research vary.

As one example, the effectiveness of implicit social pressure in direct mail in the United States evidently remains inconclusive. The motivation for this research is the observation that voting is a social norm responsive to others’ impressions (Blais, 2000; Gerber & Rogers, 2009). However, some evidence suggests that explicit social pressure to mobilise voters (e.g., by disclosing their vote histories) may seem invasive and can backfire (Matland & Murray, 2013). In an attempt to preserve the benefits of social pressure while mitigating its drawbacks, researchers have explored whether implicit social pressure in direct mail (i.e., mailers with an image of eyes, reminding recipients of their social responsibility) boosts turnout on election day. Of their evaluation of implicit social pressure, which had apparently been regarded as effective, political scientists Richard Matland and Gregg Murray concluded that, “The effects are substantively and statistically weak at best and inconsistent with previous findings” (Matland & Murray, 2016). In response to similar, repeated findings from Matland and Murray, Costas Panagopoulos wrote that their work in fact “supports the notion that eyespots likely stimulate voting, especially when taken together with previous findings” (Panagopoulos, 2015). Panagopoulos soon thereafter authored a paper arguing that the true impact of implicit social pressure actually varies with political identity, claiming that the effect is pronounced for Republicans but not for Democrats or Independents, while Matland maintained that the effect is "fairly weak" (Panagopoulos & van der Linden, 2016; Matland, 2016).

Similarly, studies on the effects of door-to-door canvassing lack consensus (Bhatti et al., 2019). Donald Green, Mary McGrath, and Peter Aronow published a review of seventy-one canvassing experiments and found their average impact to be robust and credible (Green, McGrath, & Aronow, 2013). A number of other experiments have demonstrated that canvassing can boost voter turnout outside the American-heavy literature: among students in Beijing in 2003, with British voters in 2005, and for women in rural Pakistan in 2008 (Guan & Green, 2006; John & Brannan, 2008; Giné & Mansuri, 2018). Studies from Europe, however, call into question the generalisability of these findings. Two studies on campaigns in 2010 and 2012 in France both produced ambiguous results, as the true effect of canvassing was not credibly positive (Pons, 2018; Pons & Liegey, 2019). Experiments conducted during the 2013 Danish municipal elections observed no definitive effect of canvassing, while Enrico Cantoni and Vincent Pons found that visits by campaign volunteers in Italy helped increase turnout, but those by the candidates themselves did not (Bhatti et al., 2019; Cantoni & Pons, 2017). In some cases, the effect of door-to-door canvassing was neither positive nor ambiguous but distinctly counterproductive. Florian Foos and Peter John observed that voters contacted by canvassers and given leaflets for the 2014 British European Parliament elections were 3.7 percentage points less likely to vote than those in the control group (Foos & John, 2018). Putting these together, the effects of canvassing still seem positive in Europe, but they are less pronounced than in the US. This learning has led some scholars to note that “practitioners should be cautious about assuming that lessons from a US- dominated field can be transferred to their own countries’ contexts” (Bhatti et al., 2019).

A cursory glance at a selection of literature related to these two cases alone – implicit social pressure and canvassing – illustrates how tricky answering “Does it work?” is. Although many of the technologies in use today are personal data-supercharged analogues of these antecedents (e.g., canvassing apps with customised scripts and talking points based on data about each household’s occupants instead of generic, door-to-door knocking), I have no reason to suspect that analyses of data-powered technologies would be any different. The short answer to “Does it work?” is that it depends. It depends on baseline voter turnout rates, print vs. digital media, online vs. offline vs. both combined, targeting young people vs. older people, reaching members of a minority group vs. a majority group, partisan vs. nonpartisan messages, cultural differences, the importance of the election, local history, and more. Indeed, factors like the electoral setup may alter the effectiveness of a technology altogether. A tool for political persuasion might work in a first-past-the-post contest in the United States but not in a European system of proportional representation in which winner-take-all stakes may be tempered. This is not to suggest that asking “Does it work?” is a futile endeavour – indeed there are potential democratic benefits to doing so – but rather that it is both limited in scope and rather abstract given the multitude of factors and conditions at play in practice.

Political calculus and algorithmic contagion

With this in mind, I submit that a more useful approach to appreciating the full impacts of data-driven elections may be a consideration of the preconditions that allow data-intensive practices to thrive and an examination of their consequences than a preoccupation with the efficacy of the practices themselves.

In a piece published in 1986, philosopher Ian Hacking coined the term ‘semantic contagion’ to describe the process of ascribing linguistic and cultural currency to a phenomenon by naming it and thereby also contributing to its spread (Hacking, 1999). I propose that the prevailing political calculus, spurred on by the commercial success of “big data” and “AI”, appears overtaken by an ‘algorithmic contagion’ of sorts. On one level, algorithmic contagion speaks to the widespread logic of quantification. For example, understanding an individual is difficult, so data brokers instead measure people along a number of dimensions like level of education, occupation, credit score, and others. On another level, algorithmic contagion in this context describes an interest in modelling anything that could be valuable to political decision-making, as Market Predict’s political page suggests. It presumes that complex phenomena, like an individual’s political whims, can be predicted and known within the structures of formalised algorithmic process, and that they ought to be. According to the Wall Street Journal, a company executive claimed that Market Predict’s “agent-based modelling allows the company to test the impact on voters of events like news stories, political rallies, security scares or even the weather” (Davies, 2019).

Algorithmic contagion also encompasses a predetermined set of boundaries. Thinking within the capabilities of algorithmic methods prescribes a framework to interpret phenomena within bounds that enable the application of algorithms to those phenomena. In this respect, algorithmic contagion can influence not only what is thought but also how. This conceptualisation of algorithmic contagion encompasses the ontological (through efforts to identify and delineate components that structure a system, like an individual’s set of beliefs), the epistemological (through the iterative learning process and distinction drawn between approximation and truth), and the rhetorical (through authority justified by appeals to quantification).

This algorithmic contagion-informed formulation of politics bears some connection to the initial “Does it work?” query but expands the domain in question to not only the applications themselves but also to the components of the system in which they operate – a shift that an honest analysis of data-driven elections, and not merely ad-based micro-targeting, demands. It explains why and how a candidate for mayor in Taipei in 2014 launched a viral social media sensation by going to a tattoo parlour. He did not visit the parlour to get a tattoo, to chat with an artist about possible designs, or out of a genuine interest in meeting the people there. He went because a digital listening company that mines troves of data and services campaigns across southeast Asia generated a list of actions for his campaign that would generate the most buzz online, and visiting a tattoo parlour was at the top of the list.

As politics continues to evolve in response to algorithmic contagion and to the data industrial complex governing the commercial (and now also political) zeitgeist, it is increasingly concerned with efficiency and speed (Schechner & Peker, 2018). Which influencer voters must we win over, and whom can we afford to ignore? Who is both the most likely to turn out to vote and also the most persuadable? How can our limited resources be allocated as efficiently as possible to maximise the probability of winning? In this nascent approach to politics as a practice to be optimised, who is deciding what is optimal? Relatedly, as the infrastructure of politics changes, who owns the infrastructure upon which more and more democratic contests are waged, and to what incentives do they respond?

Voters are increasingly treated as consumers – measured, ranked, and sorted by a logic imported from commerce. Instead of being sold shoes, plane tickets, and lifestyles, voters are being sold political leaders, and structural similarities to other kinds of business are emerging. One challenge posed by data-driven election operations is the manner in which responsibilities have effectively been transferred. Voters expect their interests to be protected by lawmakers while indiscriminately clicking “I Agree” to free services online. Efforts to curtail problems through laws are proving to be slow, mired in legalese, and vulnerable to technological circumvention. Based on my conversations with them, venture capitalists are reluctant to champion a transformation of the whole industry by imposing unprecedented privacy standards on their budding portfolio companies, which claim to be merely responding to the demands of users. The result is an externalised cost shouldered by the public. In this case, however, the externality is not an environmental or a financial cost but a democratic one. The manifestation of these failures include the disintegration of the public sphere and a shared understanding of facts, polarised electorates embroiled in 365-day-a-year campaign cycles online, and open campaign finance and conflict of interest loopholes introduced by data-intensive campaigning, all of which are exacerbated by a growing revolving door between the tech industry and politics (Kreiss & McGregor, 2017).

Personal data and political expediency

One response to Cambridge Analytica is “Does psychometric profiling of voters work?” (Rosenberg et al., 2018). A better response examines what the use of psychometric profiling reveals about the intentions of those attempting to acquire political power. It asks what it means that a political campaign was apparently willing to invest the time and money into building personality profiles of every single adult in the United States in order to win an election, regardless of the accuracy of those profiles, even when surveys of Americans indicate that they do not want political advertising tailored to their personal data (Turow et al., 2012). And it explores the ubiquity of services that may lack Cambridge Analytica’s sensationalised scandal but shares the company’s practice of collecting and using data in opaque ways for clearly political purposes.

The ‘Influence Industry’ underlying this evolution has evangelised the value of personal data, but to whatever extent personal data is an asset, it is also a liability. What risks do the collection and use of personal data expose? In the language of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), who are the data controllers, and who are the data subjects in matters of political data which is, increasingly, all data? In short, who gains control, and who loses it?

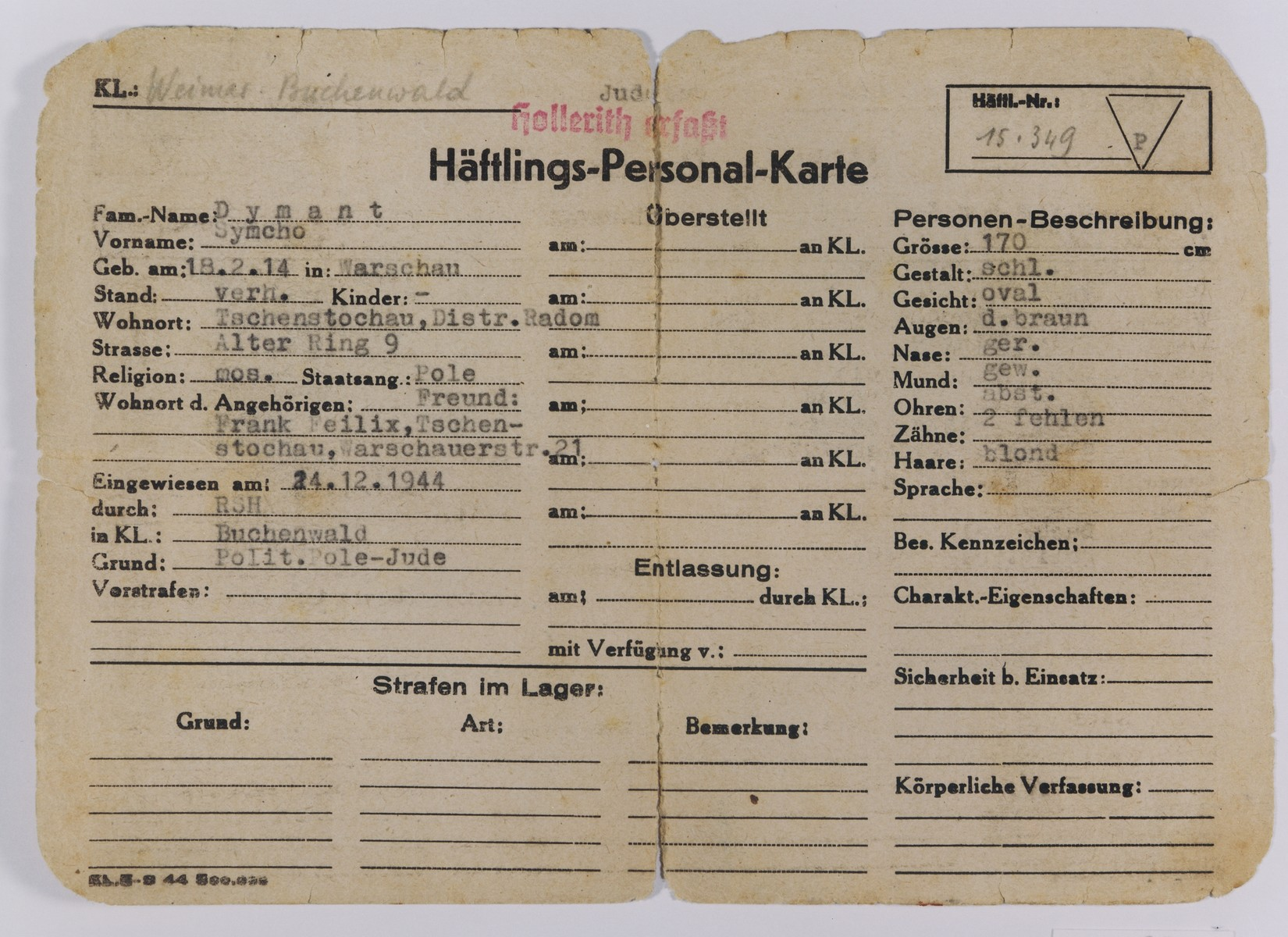

As a member of a practitioner-oriented group based in Germany with a grounding in human rights, I worry about data-intensive practices in elections and the larger political sphere going awry, especially as much of our collective concern seems focused on questions of efficacy while companies race to capitalise on the market opportunity. For historical standards of the time, the Holocaust was a ruthlessly data-driven, calculated, and efficient undertaking fuelled by vast amounts of personal data. As Edwin Black documents in IBM & The Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance between Nazi Germany and America's Most Powerful Corporation, personal data managed by IBM was an indispensable resource for the Nazi regime. IBM’s President at the time, Thomas J. Waston Sr., the namesake of today’s IBM Watson, went to great lengths to profit from dealings between IBM’s German subsidiary and the Nazi party. The firm was such an important ally that Hitler awarded Watson an Order of the German Eagle award for his invaluable service to the Third Reich. IBM aided the Nazi’s record-keeping across several phases of the Holocaust, including identification of Jews, ghettoisation, deportation, and extermination (Black, 2015). Black writes that “Prisoners were identified by descriptive Hollerith cards, each with columns and punched holes detailing nationality, date of birth, marital status, number of children, reason for incarceration, physical characteristics, and work skills” (Black, 2001). These Hollerith cards were sorted in machines physically housed in concentration camps.

The precursors to these Hollerith cards were originally developed to track personal details for the first American census. The next American census, to be held in 2020, has already been a highly politicised affair with respect to the addition of a citizenship question (Ballhaus & Kendall, 2019). President Trump recently abandoned an effort to formally add a citizenship question to the census, vowing to seek this information elsewhere, and the US Census Bureau has already published work investigating the quality of alternate citizenship data sources for the 2020 Census (Brown et al., 2018). For stakeholders interested in upholding democratic ideals, focusing on the accuracy of this alternate citizenship data is myopic; that an alternate source of data is being investigated to potentially advance an overtly political goal is the crux of the matter.

This prospect may seem far-fetched and alarmist to some, but I do not think so. If the political tide were to turn, the same personal data used for a benign digital campaign could be employed in insidious and downright unscrupulous ways if it were ever expedient to do so. What if a door-to-door canvassing app instructed volunteers walking down a street to skip your home and not remind your family to vote because a campaign profiled you as supporters of the opposition candidate? What if a data broker classified you as Muslim, or if an algorithmic analysis of your internet browsing history suggests that you are prone to dissent? Possibilities like these are precisely why a fixation on efficacy is parochial. Given the breadth and depth of personal data used for political purposes, the line between consulting data to inform a political decision and appealing to data – given the rhetorical persuasiveness it enjoys today – in order to weaponise a political idea is extremely thin.

A holistic appreciation of data-driven elections’ democratic effects demands more than simply measurement, and answering “Does it work?” is merely one component of grasping how campaigning transformed by technology and personal data is influencing our political processes and the societies they engender. As digital technologies continue to rank, prioritise, and exclude individuals even when – indeed, especially when – inaccurate, we ought to consider the larger context in which technological practices shape political outcomes in the name of efficiency. The infrastructure of politics is changing, charged with an algorithmic contagion, and a well-rounded perspective requires that we ask not only how these changes are affecting our ideas of who can participate in our democracies and how they do so, but also who derives value from this infrastructure and how they are incentivised, especially when benefits are enjoyed privately but costs sustained democratically. The quantitative tools underlying the ‘datafication’ of politics are neither infallible nor safe from exploitation, and issues of accuracy grow moot when data-intensive tactics are enlisted as pawns in political agendas. A new political paradigm is emerging whether or not it works.

References

Ballhaus, R., & Kendall, B. (2019, July 11). Trump Drops Effort to Put Citizenship Question on Census, The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/trump-to-hold-news-conference-on-census-citizenship-question-11562845502

Bhatti, Y., Olav Dahlgaard, J., Hedegaard Hansen, J., & Hansen, K.M. (2019). Is Door-to-Door Canvassing Effective in Europe? Evidence from a Meta-Study across Six European Countries, British Journal of Political Science, 49(1), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123416000521

Black, E. (2015, March 17). IBM’s Role in the Holocaust -- What the New Documents Reveal. HuffPost. Retrieved from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/ibm-holocaust_b_1301691

Black, E. (2001). IBM & The Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance between Nazi Germany and America's Most Powerful Corporation. New York: Crown Books.

Blais, A. (2000). To Vote or Not to Vote: The Merits and Limits of Rational Choice Theory. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt5hjrrf

Brown, J. D., Heggeness, M. L., Dorinski, S., Warren, L., & Yi, M.. (2018). Understanding the Quality of Alternative Citizenship Data Sources for the 2020 Census [Discussion Paper No. 18-38] Washington, DC: Center for Economic Studies. Retrieved from https://www2.census.gov/ces/wp/2018/CES-WP-18-38.pdf

Cantoni, E., & Pons, V. (2017). Do Interactions with Candidates Increase Voter Support and Participation? Experimental Evidence from Italy [Working Paper No. 16-080]. Boston: Harvard Business School. Retrieved from https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Publication%20Files/16-080_43ffcfcb-74c2-4713-a587-ebde30e27b64.pdf

Davies, P. (2019). A New Crystal Ball to Predict Consumer and Investor Behavior. Wall Street Journal, June 10. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-new-crystal-ball-to-predict-consumer-and-investor-behavior-11560218820?mod=rsswn

Foos, F., & John, P. (2018). Parties Are No Civic Charities: Voter Contact and the Changing Partisan Composition of the Electorate*, Political Science Research and Methods, 6(2), 283–98. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2016.48

Gerber, A. S., & Rogers, T. (2009). Descriptive Social Norms and Motivation to Vote: Everybody’s Voting and so Should You. The Journal of Politics, 71(1), 178–191. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381608090117

Giné, X. & Mansuri, G. (2018). Together We Will: Experimental Evidence on Female Voting Behavior in Pakistan. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 10(1), 207–235. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20130480

Green, D.P., McGrath, M. C. & Aronow, P. M. (2013). Field Experiments and the Study of Voter Turnout. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 23(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2012.728223

Guan, M. & Green, D. P. (2006). Noncoercive Mobilization in State-Controlled Elections: An Experimental Study in Beijing. Comparative Political Studies, 39(10), 1175–1193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414005284377

Hacking, I. (1999). Making Up People. In M. Biagioli (Ed.), The Science Studies Reader (pp. 161–171). New York: Routledge. Retrieved from http://www.icesi.edu.co/blogs/antro_conocimiento/files/2012/02/Hacking_making-up-people.pdf

John, P., & Brannan, T. (2008). How Different Are Telephoning and Canvassing? Results from a ‘Get Out the Vote’ Field Experiment in the British 2005 General Election. British Journal of Political Science, 38(3), 565–574. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000288

Kreiss, D., & McGregor, S. C. (2017). Technology Firms Shape Political Communication: The Work of Microsoft, Facebook, Twitter, and Google With Campaigns During the 2016 U.S. Presidential Cycle, Political Communication, 35(2), 155–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1364814

Matland, R. (2016). These Eyes: A Rejoinder to Panagopoulos on Eyespots and Voter Mobilization, Political Psychology, 37(4), 559–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12282 Available at https://www.academia.edu/12128219/These_Eyes_A_Rejoinder_to_Panagopoulos_on_Eyespots_and_Voter_Mobilization

Matland, R. E. & Murray, G. R. (2013). An Experimental Test for ‘Backlash’ Against Social Pressure Techniques Used to Mobilize Voters, American Politics Research, 41(3), 359–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X12463423

Matland, R. E., & Murray, G. R. (2016). I Only Have Eyes for You: Does Implicit Social Pressure Increase Voter Turnout? Political Psychology, 37(4), 533–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12275

Panagopoulos, C. (2015). A Closer Look at Eyespot Effects on Voter Turnout: Reply to Matland and Murray, Political Psychology, 37(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12281

Panagopoulos, C. & van der Linden, S. (2016). Conformity to Implicit Social Pressure: The Role of Political Identity, Social Influence, 11(3), 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2016.1216009

Pons, V. (2018). Will a Five-Minute Discussion Change Your Mind? A Countrywide Experiment on Voter Choice in France, American Economic Review, 108(6), 1322–1363. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20160524

Pons, V., & Liegey, G. (2019). Increasing the Electoral Participation of Immigrants: Experimental Evidence from France, The Economic Journal, 129(617), 481–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12584 Retrieved from https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=53575

Rosenberg, M., Confessore, N., & Cadwalladr, C. (2018, March 17). How Trump Consultants Exploited the Facebook Data of Millions, The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/17/us/politics/cambridge-analytica-trump-campaign.html

Schechner, S. & Peker, E. (2018, October 24). Apple CEO Condemns ‘Data-Industrial Complex’, Wall Street Journal, October 24.

Turow, J., Delli Carpini, M. X., Draper, N. A., & Howard-Williams, R. (2012). Americans Roundly Reject Tailored Political Advertising [Departmental Paper No. 7-2012]. Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/398

Add new comment