The platform governance triangle: conceptualising the informal regulation of online content

Abstract

From the new Facebook ‘Oversight Body’ for content moderation to the ‘Christchurch Call to eliminate terrorism and violent extremism online,’ a growing number of voluntary and non-binding informal governance initiatives have recently been proposed as attractive ways to rein in Facebook, Google, and other platform companies hosting user-generated content. Drawing on the literature on transnational corporate governance, this article reviews a number of informal arrangements governing online content on platforms in Europe, mapping them onto Abbott and Snidal’s (2009) ‘governance triangle’ model. I discuss three key dynamics shaping the success of informal governance arrangements: actor competencies, ‘legitimation politics,’ and inter-actor relationships of power and coercion.This paper is part of Transnational materialities, a special issue of Internet Policy Review guest-edited by José van Dijck and Bernhard Rieder.

Introduction

On 15 November 2018, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg published a long essay titled “A Blueprint for Content Governance and Enforcement”. In it, he claimed that he had “increasingly come to believe that Facebook should not make so many important decisions about free expression and safety on [its] own”, and as a result, would create an “Oversight Body” for content moderation that would let users appeal takedown decisions to an independent body (Zuckerberg, 2018, n.p). In May 2019, New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and French President Emmanuel Macron unveiled the Christchurch Call, a non-binding set of commitments to combat terrorist content online signed by eighteen governments and eight major technology firms.

Such initiatives are becoming increasingly commonplace as debates around harmful or illegal content have resurfaced as a major international regulatory issue (Kaye, 2019; Wagner, 2013). The current “platform governance” status quo — understood as the set of legal, political, and economic relationships structuring interactions between users, technology companies, governments, and other key stakeholders in the platform ecosystem (Gorwa, 2019) — is rapidly moving away from an industry self-regulatory model and towards increased government intervention (Helberger, Pierson, & Poell, 2018). As laws around online content passed in countries like Germany, Singapore, and Australia have raised significant concerns for freedom of expression and digital rights advocates (Keller, 2018a), various actors are proposing various voluntary commitments, principles, and institutional oversight arrangements as a better way forward (ARTICLE 19, 2018). Important voices, such as the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression, David Kaye, have expressed hope that such models could help make platform companies more transparent, accountable, and human-rights compliant (Kaye, 2018).

How should these emerging efforts be understood? In this article, I show that various forms of non-binding and informal “regulatory standards setting” have long been advanced to govern the conduct of transnational corporations in industries from natural resources to manufacturing, and in recent years, have become increasingly popular — especially in Europe — as a way to set content standards for social networking platforms. Drawing upon the global corporations literature from international relations and international political economy, I provide a proof-of-concept mapping to show how Abbott and Snidal’s (2009) “governance triangle” model can be used to analyse major content governance initiatives like the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation or the Facebook Oversight Board. After mapping out the informal content regulation landscape in Europe in a ‘platform governance triangle’ that helps visualise the breakdown of different actors in informal regulatory arrangements, I present three key arguments from the literature on corporate governance that the internet policy community should be mindful of as informal measures proliferate further: (a) the importance of varying actor competencies in different governance initiatives, (b) the difficult dynamics of ‘legitimation politics’ between different initiatives (and between voluntary governance arrangements and traditional command-and-control regulation), and (c) the layers of power relations manifest in the negotiation and implementation of informal governance measures.

The platform governance challenge

In February 2019, the United Kingdom’s Digital, Media, Culture, and Sport (DCMS) committee wrapped up its sixteen-month inquiry into “Disinformation and Fake News” with the publication of probably the most scathing indictment of American technology companies published by a democratic government. The report, which was released only a few weeks after the anniversary of Facebook’s fifteenth year of operation, memorably quipped that the company had operated as a “digital gangster”, exhibiting anti-competitive behaviour and a reckless disregard for user privacy (Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee, 2019, p. 91). One of the main themes in the commission’s report was responsibility: as they wrote, “Social media companies cannot hide behind the claim of being merely a ‘platform’ and maintain that they have no responsibility themselves in regulating the content of their sites” (Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee, 2019, p. 10).

A term that once encapsulated what Zittrain (2008, p. 2) called “generativity” — the ability for an object to be built on and adapted in ways beyond its initial purpose, and perhaps even beyond what its creators could have even imagined — has since become imbued with assumptions about political and social responsibility that policymakers are increasingly expressing displeasure with today. As Tarleton Gillespie and others have argued, the legally-enshrined conceptual framing of a “platform” that merely hosts content, but should not be held legally liable for it, became a strategic and powerful enabler for the rise of today’s digital giants (Andersson Schwarz, 2017; Gillespie, 2010). 1 Ample scholarship has since shown that the framing of technology companies as mere “hosts” or “intermediaries” or “platforms” elides the ways in which these companies set (oft-American) norms around content or speech (Klonick, 2017), algorithmically select and present information (Bucher, 2018), and assume a host of functions that combine features of publishers, media companies, telecommunications providers, and other firms (Napoli & Caplan, 2017). Since the 2016 US election, increasing public attention has been paid to how firms “moderate,” making important decisions about the users and types of speech they permit (Roberts, 2018), and governments around the world are steadily seeking to increase place decisions about online speech back into the hands of their citizens.

Regulating platform companies is easier said than done, however (Lynskey, 2017). There are many prospective challenges, which range from the relative novelty of their business models, significant freedom of expression challenges posed by some varieties of government intervention, the lack of meaningful policy experimentation and precedent to point to, concerns about stifling future innovation, as well as classic regulatory concerns about compliance, enforcement, and efficacy. These are compounded by the fact that many platforms are “data monopolies” and black boxes that are difficult to see into (Finck, 2017, p. 20; Marsden, 2018), leaving regulators scrambling to address certain issues or perceived harms that are yet to be properly documented by empirical research. Furthermore, platform companies tend to be large international businesses that host content from users across many jurisdictions, adding a new spin on the always-difficult regulatory and legal questions posed by multinational corporations.

The evolution of corporate governance

How can corporations be governed? While an intellectual history of thinking about corporations as transnational actors can go back centuries (Risse, 2002), the wave of attention about corporations as political actors in global affairs began in the 1970s or so (Strange, 1991; Vernon, 1977). The post-WW2 international order, characterised by increasing interdependence through international organisations, institutions, and trade, enabled firms to expand globally, to the extent that transnational companies became “the most visible embodiment of globalization” (Ruggie, 2007, p. 821) during the 1990s and early 2000s. As the activity of firms became intertwined with virtually all important global social issues, from climate change and environmental damage to human rights and labour standards, corporations raised a vital set of governance puzzles (Fuchs, 2007; Hall & Biersteker, 2002). How could one get corporations to comply with human rights standards that were crafted specifically for states (Dingwerth & Pattberg, 2009)? How could firm behaviour be regulated across jurisdictions, and how could firms be nudged into more responsible business practices, often at the expense of their overall bottomline (Mikler, 2018)?

The traditional answer has been “command and control” regulation (Black, 2001, p. 105), where governments seek to make corporations comply under threat of legal and financial penalties. However, it is not always easy to pass such regulation, as industry lobbies heavily to protect its interests, and even once rules are in effect, ensuring compliance — especially when firms are headquartered in different jurisdictions — is no easy task (Marsden, 2011; Simpson, 2002). From environmental issues to overreach in the financial sector, firm behaviour can generate major negative social, political, and economic externalities, and both governments and international organisations have often failed to produce adequate solutions (Hale, Held, & Young, 2013). As Ruggie (2007, p. 821) put it, “the state-based system of global governance has struggled for more than a generation to adjust to the expanding reach and growing influence of transnational corporations.”

One stopgap measure has been the growing number of private organisations created to govern corporate behaviour through voluntary standards and transnational rules (Büthe & Mattli, 2011; Dingwerth & Pattberg, 2009). Some of the earliest instances of this trend involved codes of conduct, often initiated under the umbrella of large international organisations, such as the World Health Organization, which notably agreed to a code of conduct with Nestlé in 1984 after a multi-year consumer boycott and international activist campaign (Sikkink, 1986). Since then, initiatives have been increasingly developed by groups of NGOs and industry groups, with dozens of efforts that have sought to create standards and outline best practices around sustainability (e.g., ISO14001, the Forest Stewardship Council), labour rights (e.g., the Fair Labour Association, the Workers Rights Consortium) and many other areas (Fransen & Kolk, 2007).

Transnational regulatory schemes can take many forms (Bulkeley et al., 2012). Some are insular industry associations that enact self-regulatory codes, while others are broader initiatives that bring together a host of different actors, and often include participation from civil society or government (Fransen, 2012). The latter type of institutional arrangement is often referred to as “multistakeholder governance”, which Raymond & DeNardis (2015, p. 573) define “as two or more classes of actors engaged in a common governance enterprise concerning issues they regard as public in nature, and characterized by polyarchic authority relations constituted by procedural rules.” In other words, it is governance involving actors from at least two of four groups — states, non-governmental organisations (including civil society, researchers, and other parties), firms, and international organisations like the United Nations — where decision making authority is distributed across a in a ‘polyarchic’ or ‘polycentric’ arrangement where one actor does not make decisions unilaterally (Black, 2008).

The result has been variously described as ‘new governance’, ‘transnational governance’, or ‘transnational new governance’ (Abbott & Snidal, 2009a). The core novelty in these new regulatory arrangements is the “central role of private actors, operating singly and through novel collaborations, and the correspondingly modest and largely indirect role of ‘the state’, as well as the fact that ”most of these arrangements are governed by firms and industry groups whose own practices or those of supplier firms are the targets of regulation" (Abbott & Snidal, 2009a, p. 505).

Private regulatory standards and the governance triangle

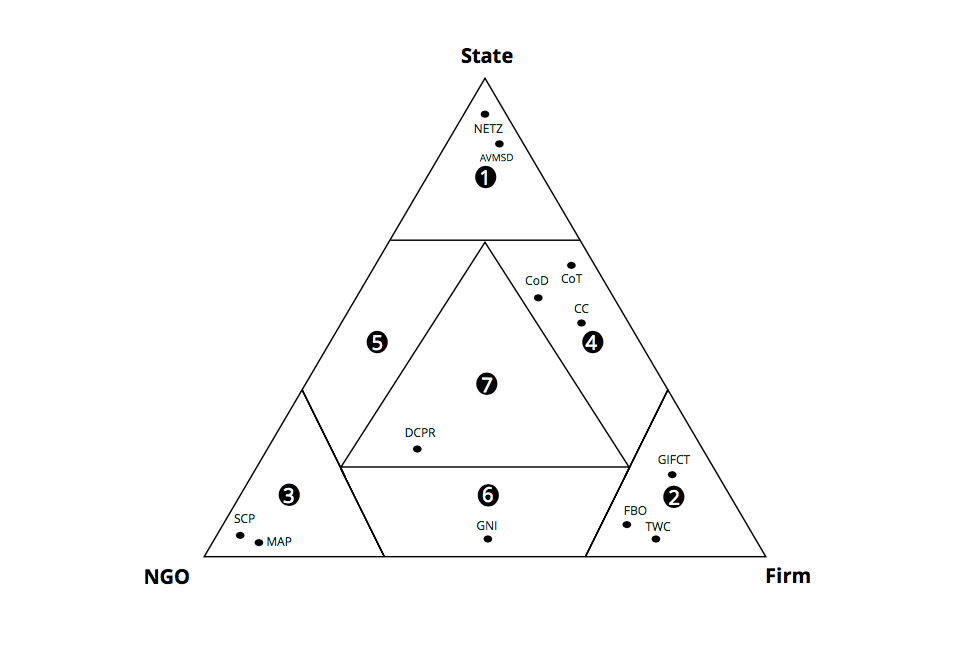

A consequence of this move towards more global and more private governance has been a complex and overlapping set of regulatory initiatives with varying degrees of formality. The regulatory landscape thus includes not only traditional forms of regulation, but a host of voluntary arrangements, public-private partnerships, industry-specific measures, and more. In order to help “structure analysis of widely varying forms of governance”, Abbott and Snidal (2009b, p. 52) outline the conceptual model of the “Governance Triangle” to help represent the groupings of actors and interests in governance schemes that create rules and processes for participating actors.

There are three major groupings of actors: ‘firm’, which is composed of individual companies as well as industry associations and other groupings of companies; ‘NGO’, which is a broad category including civil society groups, international non-governmental organisations, academic researchers, activist investors, and individuals; and ‘state’, which includes both individual governments as well as supranational groupings of governments (e.g., the European Union, the United Nations). 2 Initiatives may involve just one type of actor, or dyads with representation from both firms and government or civil society and firms. Some processes, emblematic of the classic notion of multistakeholderism, involve some form of decision making distributed across actors.

This graph therefore offers a snapshot of the global ecosystem of corporate regulation. Abbott and Snidal (2009b, p. 52) try to position each dot (representing a regulatory initiative) in the triangle based on the approximate amount of influence (“governance shares”) that each actor exerts over it. At the top of the triangle (labelled #1) they place processes dominated by states, such as the 1978 German “Blue Angel” eco-labeling scheme (marked ECO). In the right corner (#2) are arrangements controlled by firms, ranging from the individual supply chain transparency projects of a company like GAP to industry-wide certification schemes like the 1994 ‘Sustainable Forestry Initiative’ (SFI). In the left corner (#3) are NGO efforts, such as the Sullivan principles spearheaded by civil society during the Apartheid boycott. All the other zones involve combinations of actors. For example, the UN Global Compact (UNGC) was largely executed by states (through the UN) with some firm involvement, and the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) is governed by a mix of NGOs and firms. In the centre are schemes like the the Kimberly Process for conflict diamonds (KIMB), which involved a mix of NGO, state, and firm voices.

The model is intended to serve as a heuristic, so “the boundaries of zones and the placement of points are not intended as precise representations of complex arrangements” (Abbott & Snidal, 2009b, pp. 52–53). Relative location is more important than specific placement on one zone boundary or another, which is by necessity subjective and debatable. The approach is also limited in that combines different actors in each subgroup (eliding perhaps the differing influence of certain NGOs or firms involved in an initiative). That said, it remains a useful and intuitive analytical framework, allowing one to visualise trends over time — for example, the evolution and significant proliferation of corporate governance schemes over time seen in Figure 2.

Platform companies and regulatory standards for free expression

What does the governance landscape in Europe and North America look like for today’s major platform companies? Just as in other industries, there appears to have been an increase in transnational regulatory standards setting arrangements in the past two decades. As Marsden (2011, p. 11) writes, internet regulation in Europe moved towards “self-regulation in the 1990s, re-regulation and state interest in the early 2000s, and now increasingly [towards] co-regulation in the period since about 2005”. Under arrangements like the E-Commerce Directive of 2000, online intermediaries (including social networks and the big platform companies of today) were given broad leeway, with limited legal liability over individual pieces of content as long as they had notice-and-takedown systems for things like copyright infringement in place (Keller, 2018b). On transnational privacy issues, industry was permitted to self-certify, allowing American firms to profess their adherence to codes of conduct (and therefore, legal adequacy with EU data protection legislation) created under supervision and enshrined in privacy agreements such as the EU-US Safe Harbour (Poullet, 2006, p. 210). Voluntary codes of conduct became a key part of the global privacy regime (Hirsch, 2013, p. 1046). In the US, a host of voluntary programmes attempted, less successfully, to apply voluntary forms of regulation to the American digital marketing, data broker, online advertising, and other industries (Kaminski, 2015; Rubinstein, 2018).

Once platforms hosting user content became popular, governments quickly sought to limit their citizens’ access to illegal material (Goldsmith & Wu, 2006). Using the governance triangle, we can sketch out the informal regulatory climate for content on platforms that host user-generated content (Figure 3). As I will demonstrate, informal regulatory arrangements have formed a key tool through which governance stakeholders — especially EU governments — have sought to shape the behaviour of firms on content issues. I break these down into the pairings of actors involved (Table 1), and briefly discuss some notable arrangements in the following section. This is a necessarily limited proof-of-concept analysis, and I do not intend to provide a complete mapping of all of the relevant actors, organisations, or initiatives in the platform governance space — instead, I hope that this analysis provides a useful mental model of interactions between actors and can be expanded to other areas such as data protection or cybersecurity.

|

Name |

Date |

Actors |

Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG) |

2017 |

State |

National |

|

Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD) |

2018 |

State |

Regional |

|

Dynamic Coalition on Platform Responsibility (DCPR) |

2014 |

State-Firm-NGO |

Global |

|

Safer Social Networking Principles (SSP) |

2009 |

State-Firm |

Regional |

|

EU Code of Conduct on Terror and Hate Content (CoT) |

2017 |

State-Firm |

Regional |

|

EU Code of Practice on Disinformation (CoD) |

2018 |

State-Firm |

Regional |

|

Christchurch Call (CC) |

2019 |

State-Firm |

Global |

|

Global Network Initiative (GNI) |

2008 |

Firm-NGO |

Global |

|

Twitter Trust and Safety Council (TWC) |

2016 |

Firm |

Global |

|

Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT) |

2018 |

Firm |

Global |

|

Facebook Oversight Body (FBO) |

2019 |

Firm |

Global |

|

Manila Principles on Intermediary Liability (MAP) |

2015 |

NGO |

Global |

|

Santa Clara Principles on Content Moderation (SCP) |

2018 |

NGO |

Global |

Single actor

State

Traditional forms of ‘hard’ regulation set rules and standards without direct collaboration from other stakeholders. At the national level, laws like the EU E-Commerce Directive have importantly established baseline provisions for intermediary liability. Newer legal frameworks — such as the German “Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz” (NetzDG), the EU Audiovisual Media Service Directive (AVMSD), or the much discussed EU Copyright Directive — tweak these liability provisions at the national or regional level. Under NetzDG, social networks with more than 2 million users in Germany can be found liable if they do not rapidly remove illegal content according to German law (Schulz, 2018). AVMSD focuses on ‘video-sharing platforms’, and includes both TV broadcasts and streaming services like YouTube in its scope. Like NetzDG, it also mandates some transparency requirements, but also is more careful in that it seeks to combat the incentive to over-block by instituting proportionality and redress requirements (Kuklis, 2019). While it is not the focus of this article, and has been examined in depth elsewhere (see e.g., Puppis, 2010; Wagner, 2016), state-based content regulation provides the baseline upon which informal governance arrangements tend to build — either as complements intended to fill in certain gaps, or as substitutes to proposals perceived as overly invasive or harmful to human rights.

NGO

Digital civil society groups, academics, and journalists have come to play a vital corporate accountability and watchdog function through their advocacy, research, and investigations into platform practices (Gorwa, 2019). In the past several years, NGOs have also put forth a few sets of principles to spur public discussion and affect the governance landscape by providing policy resources for firms and governments. These include the ‘International Principles on the Application of Human Rights to Communications Surveillance’, which were spearheaded by Access Now, the EFF, and Privacy International following the Snowden revelations and have been endorsed by more than 400 civil society organisations (Stepanovich & Mitnick, 2015, p. 3). In 2014 and 2015, a group of global digital rights organisations developed the ‘Manila Principles on Intermediary Liability’, which articulate the position that intermediaries (internet service providers (ISPs), social networks, and hosting platforms) should not have legal liability over third-party content, and that content restriction requests should be transparent and respect due process. In 2018, a small group of civil society groups and researchers, once again including the EFF, proposed the ‘Santa Clara Principles for Content Moderation’ (SCPs). The SCPs differ from the previous two efforts by specifically providing recommendations for firms, rather than governments, and advocate for specific recommendations on how companies should meet basic best practices for appeals, user notice, and transparency in their moderation processes. These three sets of principles appear to have been almost entirely civil society efforts, with little industry or government involvement.

Industry

Firms often develop single-actor self-regulatory initiatives pictured in Zone 2 of Fig. 3 as a way to improve their bargaining position with other actors, to win public relations points, and to evade more costly regulation (Abbott & Snidal, 2009b, p. 71). Despite many years of concern that Twitter was enabling toxic threats, harassment, and abuse (Amnesty International, 2018), the company did not enact a policy prohibiting hate speech until the end of 2015 (Matamoros-Fernandez, 2018, p. 39). It followed that change by creating an organisation called the ‘Twitter Trust and Safety Council’, which brings together about fifty community groups, civil society organisations, and a handful of academics with the company’s stated goal of providing “input on our safety products, policies, and programs”. However, there has been almost no public information about organisation, reflecting traditional concerns about the transparency and accountability of corporate governance schemes (Tusikov, 2017), and it appears that the ‘Council’ is more of an informal grouping of partner organisations rather than a proper institution where the civil society organisations wield meaningful power. As such, it remains unclear what the NGOs involved gain from the project, and whether they are able to meaningfully influence any of Twitter’s policies.

Industry initiatives can also be born out of government pressure. The Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT) was created in 2017 by Facebook, Microsoft, Twitter, and YouTube in an effort that builds upon the EU Internet Forum and probably is intended to demonstrate the kind of proactive industry-wide collaboration that the four firms committed to under the EU Code of Conduct on illegal online hate speech. The organisation has a board made of “senior representatives from the four founding companies” and publishes very little about its operations. However, the organisation has stated that it has been particularly focused on the improvement of automated systems to remove extremist images, videos, and text, and it has organised a number of summits that bring together national security and defence officials with platform employees and academics.

The Facebook Oversight Body is another interesting development currently being pursued by Facebook (and the plethora of new employees it has hired for the purpose from major international institutions). The Body, which will provide some kind of oversight or input into Facebook’s content policy process, has been described by legal theorists recently as a form of “structural constitutionalism” where the company is becoming more governmental, developing a ‘judicial branch’ of sorts (Kadri & Klonick, 2019, p. 38). But it may be more accurate to simply conceptualise Facebook’s efforts as another example of a private informal governance arrangement, more akin to the many certification, advisory, and oversight bodies established in the natural resource extraction or manufacturing industries (Bulkeley et al., 2012; Haufler, 2003). While the exact design of Facebook’s initiative is yet to be seen, the company has at least discursively shifted away from the initial judicial conception (‘The Supreme Court of Facebook’) and instead moved towards the more banal ‘Oversight Board’, suggesting that this type of effort may merely represent a new chapter within the longer tradition of the tech industry’s self-regulation. Given that all three of these organisations have the capacity to make policy decisions with global speech ramifications, they remain initiatives hugely understudied and should be comprehensively examined by future research.

State-firm

‘Voluntary’ codes and principles

The European Union has a long history of applying “co-regulatory”, “self-regulatory” and “soft law” solutions to policy issues that involve corporations, from tax policy to the environment (Senden, 2005). The internet and emerging tech sectors have been no exception (Marsden, 2011), with voluntary codes of conduct and negotiated self-regulatory agreements having been applied to a range of goals such as sustainability, child safety, and data protection.

In 2008, the “Social Networking Task Force” convened multistakeholder meetings with regulators, academic experts, child safety organisations, and a group of 17 social networks, including Facebook, MySpace, YouTube, Bebo, and others. This process led to the creation of the “Safer Social Networking Principles for the EU”, described as a “major policy effort by multiple actors across industry, child welfare, educators, and governments to minimise the risks associated with social networking for children” through more intuitive privacy settings, safety information, and other design interventions (Livingstone, Ólafsson, & Staksrud, 2013, p. 317). From 2012 to 2013, this process was expanded through the “CEO Coalition to make the Internet a better place for kids”, a series of working group meetings that led to a set of five principles (“simple and robust reporting tools for users, age-appropriate privacy settings, wider use of content classification, wider availability and use of parental controls, and effective takedown of child sexual abuse material”) signed by Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, a number of EU telecoms, hardware manufacturers, and other firms (European Commission, 2013, n.p; Livingstone, Ólafsson, O’Neill, & Donoso, 2012).

Similar efforts were carried out in an effort to reduce the availability of terrorist content. In 2010, The Netherlands, the UK, Germany, Belgium and Spain sponsored a European Commission project called “Clean IT”, which would develop “general principles and best practices” to combating terrorist content and “other illegal uses of the internet [...] through a bottom up process where the private sector will be in the lead”. The Clean IT coalition, which featured significant representation from European law enforcement agencies, initially appeared to be considering some very hawkish proposals (such as requiring all platforms to enact a real-name policy, and that “Social media companies must allow only real pictures of users”), leading to a push-back from civil society and the eventual end of the project (European Digital Rights, 2013, n.p). However, the project seemed to set the ideological foundations for the EU’s approach to online terrorist content by advocating for more aggressive terms of service and industry takedowns without explicit legislation. In 2014, the European Commission announced the “EU Internet Forum”, which brought together EU governments with Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Twitter, and (bizarrely) Ask.FM to discuss how platform companies should best combat illegal hate speech and terrorist content (Fiedler, 2016). After almost two years of meetings, the companies agreed to a “Code of Conduct on illegal online hate speech”, which raises “privatised enforcement” obligations on the firms to promptly remove terrorist material and other problematic content (Coche, 2018, p. 3). It also incentivises companies to collaborate on best practices, such as the creation of hash databases for terrorist material through the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (European Commission, 2016; Twitter Policy, 2017).

One common strategy deployed by the EU involves the creation of working groups that combine voices from academia, industry, and civil society. In January 2018, 39 selected experts met as part of the High-Level Expert Group on Fake News and Disinformation, rapidly turning around a report with recommendations that informed the creation of the “Code of Practice on Online Disinformation”, which was signed by Facebook, Google, Twitter, Mozilla, and three advertising trade associations in September 2018. States commonly consult with stakeholders when developing new forms of regulation, so in this sense these working groups are not particularly novel. That said, the responsibilities in implementation are largely taken on by firms, where signatories commit (in a non-binding fashion) to improving their public disclosure of political advertising, to actively battling false accounts, and to formalise mechanisms of data-access to researchers attempting to study the effects of disinformation (European Commission, 2019). The state role, when compared with traditional command-and-control legislation, is relatively limited to more of an informal oversight and steering role.

A notable recent development is the Christchurch Call to Eliminate Terrorist and Violent Extremist Content Online, initiated by New Zealand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade after the tragic mosque shootings of March 2019. These general and non-binding commitments were signed by seventeen countries and eight firms (including Amazon, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and Twitter) and is a pledge for further informal cooperation between governments and firms (Douek, 2019).

Firm-NGO

The Global Network Initiative

The Global Network Initiative (GNI) is a multistakeholder standard-setting and accountability body that was launched in 2008 to help tech companies better deal with government requests for content takedowns or user data. As Maclay (2014) explains in a doctoral dissertation that is probably the most comprehensive publicly available analysis of the organisation, the GNI emerged amidst a multitude of social, legal, and economic pressures. Especially notable was the public scrutiny facing Yahoo, Google, and Microsoft following a number of human rights controversies, especially relating to their operations in China. US legislators were considering the “Global Online Freedom Act”, a bill introduced into Congress that would have forced American firms to follow US law and free speech norms rather than local jurisdictions (Brown, 2013; Maclay, 2014, p. 120). In 2006, representatives from these companies met in Boston (with events co-facilitated by Harvard’s Berkman Center and Business for Social Responsibility, a non-profit that had emerged as an important player in the corporate social responsibility movement of the 1990s). Other workshops happening around that time would eventually merge into one group that included civil society, academics, and representatives from firms (Maclay, 2010). Because the overarching frame of the GNI discussions was dealing with problematic government influence, “unlike in certain other multi-stakeholder dialogues, all parties agreed early in the process that governments should not participate in the dialogue” (Baumann-Pauly, Nolan, Van Heerden, & Samway, 2017, p. 780). In 2008 the GNI officially became public with Yahoo, Google, and Microsoft as founding industry members, joined by a group of NGOs, investor groups, and academics, including Human Rights Watch, the Committee to Protect Journalists, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), and a number of other groups (Maclay, 2010). In 2013, Facebook joined, and in 2017, the initiative grew to admit seven telecommunications providers, including Vodafone, Orange, and Nokia.

The GNI features three main commitments: a set of high-level principles based on international human rights law that each member company says it will internalise; guidelines on how those principles should be implemented in practice, including commitments to engage in human rights assessments and transparency reporting; and an “accountability framework” that outlines the system of oversight, including company self reporting, independent auditing, and various ‘compliance’ mechanisms (for example, if a company is seen to not be in compliance, the framework stipulates that a 120-day “special review” period can be called by the board). 3 The GNI is a fairly insular organisation, and not one that the public seems to know much about, perhaps because the public output of the GNI is limited. Participants sign non-disclosure agreements to not discuss confidential information raised during board meetings, and only the most general results of the third-party audits, for example, are made public. Relatively little scholarly work has examined its effects and impact. However, it seems to have helped spur at least some important advance for freedom of expression online: before the GNI, platforms had little way in shared best practices, and often dealt with important human rights related cases in an ad-hoc manner. The GNI Charter bound firms to increase their public transparency and in 2010, Google began issuing transparency reports and data about the amount of government takedown requests in different countries. In 2013, after it joined GNI, Facebook began doing the same, and today, it is effectively an industry-standard practice, and remains an important transparency measure, despite its many limitations.

Observations from the corporate governance literature: areas for further research

A number of general observations can be made based on the significant literature on similar forms of governance across other industries. Here, I will highlight three areas that could use further research in the platform governance space: the legitimation politics between informal arrangements and traditional regulation or other informal arrangements, the importance of the varying regulatory competencies that different actors bring to the table, and the dynamics of power, authority, and coercion between actors in the implementation of informal governance measures.

Legitimation politics

Transnational governance initiatives are generally voluntary and “non-binding”, in that they are not codified in national laws, but instead draw on other “enforcement tools”, such as market pressure, external discourse, and internal norms (Hale, 2008). As such, forms of informal governance that result in politically salient rules or standards can become fiercely contested, creating a “legitimacy politics” where different organisations compete and potentially try to undercut each other (Fransen, 2012). There is ample precedent from other industries: for instance, the Forest Stewardship Council was created in 1993 as a non-profit organisation that brought together various NGOs, firms, academics, and individuals from 60+ countries to create a certification scheme for sustainable timber (Dingwerth & Pattberg, 2009). It featured relatively high degrees of NGO involvement and imposed fairly strong standards, but not long after it was established, a group of companies introduced their own competing certification scheme, the Sustainable Forestry Initiative, which was more amenable to firm interests and as a result has been critiqued as “greenwashing” (Abbott & Snidal, 2009b).

Although Facebook’s Oversight Body has yet to be established, it has already affected the landscape for future informal governance measures. NGOs that wish to convene something like a GNI 2.0 for a host of new platform policy concerns must now contend with Facebook’s existing body, and with its potential use of scarce resources (the limited time of civil society participants is a particularly significant constraint when multiple similar initiatives proliferate). At a workshop held by Article 19 and Stanford’s Global Digital Policy Incubator in February 2019, convened to discuss the creation of a next-generation accountability body for platforms, participants grappled with how Article 19’s proposal would mesh with the recently-announced Facebook initiative (Donahoe et al., 2019). These relations will continue to become more complex as more arrangements are created.

Perhaps even more crucial are the linkages between informal governance mechanisms and traditional forms of state regulation. This remains a hotly debated area in the corporate governance literature. Established research suggests that voluntary programmes do have an effect and can be used to supplement traditional regulation and offset its high implementation costs (Potoski & Prakash, 2005). More recent work has sought to understand possible effects through surveys and experimental designs: for example, Malhotra, Monin, and Tomz (2019) suggest that voluntary commitments by firms could reduce the appetite for environmental regulation amongst key groups (including activists, the general public, and legislators), effectively undercutting it. The specific design of informal governance arrangements plays a significant role in its successes or failures, and future scholarship would do well to examine how established dynamics hold — or do not hold — when it comes to online content hosted on platform companies. Do multiple sets of stakeholder preferences coalesce through informal arrangements around a set of compromises that result in a meaningful improvement in governance outcomes, or are informal arrangements used strategically to undercut or prevent more rigorous regulation and oversight?

Actor competencies

Informal governance arrangements would not be necessary if traditional regulation was able to easily deal with today’s contemporary transnational policy issues. Different governance stakeholders have differing levels of regulatory capacity that they bring to the table: as Abbott and Snidal (2009b) argue, each type of actor has different competencies that are required at different phases of the regulatory process, from the initial agenda-setting and negotiations to the eventual implementation, monitoring, and enforcement of governance arrangements. They outline four central factors: independence, representativeness, expertise, and operational capacity (Abbott & Snidal, 2009b, p. 66). NGOs, for instance, can have high degrees of independence and representativeness, and are able to advocate for stringent standards, but they will never have the operational capacity to implement or enforce them without corporate cooperation (Fransen & Kolk, 2007). Firms are bound by their profit seeking motive and can never truly act in the public interest (therefore lacking independence and representativeness), despite their high expertise and capacity to change their behaviour. Certain states can deploy considerable resources, expertise, administrative capacity, and enforcement mechanisms, but still must rely on the management of firms to implement regulatory demands. Therefore, in “transnational settings no actor group, even the advanced democratic state, possesses all the competencies needed for effective regulation” (Abbott & Snidal, 2009b, p. 68).

Part of the challenge for standards-setting initiatives is that they do truly require collaboration: the received wisdom is that initiatives that are dominated by only one class of actors are unlikely to create meaningful reform (Fransen & Kolk, 2007). Single-actor schemes — whether they just involve NGOs or firms — often have limited long-run success, as they do not make compromises between stakeholders or bring on the right mix of competencies to actually make a difference. For instance, civil society can get together and issue principles that might provide guidance for governments or firms (e.g., the Manila or Santa Clara Principles), but only those actors can actually decide to implement them. Similarly, firm-specific initiatives are likely to not be seen as credible if they do not meaningfully collaborate with more independent and representative actors. Following this set of arguments from the literature, companies setting up ‘Oversight Bodies’ or other informal mechanisms need to devolve oversight capacity and power to NGOs (and not just hand-selected groups of sympathetic individuals) for them to be legitimate and successful over time.

Power relations

In an expansive study of the regulation of intellectual property rights and counterfeit goods on the internet, Tusikov (2016) shows how certain economically-incentivised issue groups (such as copyright holders) have sought to use informal agreements and mechanisms to privately impose content restrictions that may be widely opposed by the public when included in legislation. Compared to other industries (such as manufacturing and textiles), where civil society is a key driver and advocate for many informal governance arrangements (Vogel, 2010), the online content landscape appears to have a greater distribution of government interests (especially the European Commission and other security-focused EU actors, who have been active in negotiating codes and other informal commitments for the past decade). Public EU documentation advocates codes of conduct as a key part of contemporary technology governance, as “voluntary commitments can be implemented to react fast and pragmatically”. However, following the argument made by Tusikov (2016), firm participation in codes of conduct made by the EU might not be best understood as wholly voluntary; while the signed Codes of Conduct may be technically non-binding, they are often underpinned by the threat of future legislation, and a shared understanding that non-compliance may lead to punitive measures and potentially more stringent regulatory outcomes.

Nevertheless, the fact that those actors agreed to a non-binding arrangement is telling: contestation and bargaining occurs in all regulatory arenas, and despite the threats that may have underpinned the Codes of Conduct, all actors involved would not have agreed to them if they did not perceive gains from such an arrangement compared to their alternative. Firms get a seat at the table to shape their regulatory environment to a greater extent, and can enact voluntary commitments that are not underpinned with the same sort of sanctions as traditional legislation, while states can achieve some of their goals (e.g., measures designed to reduce terrorist content) in a far less costly manner. That said, it is crucial to better understand power relationships as enacted through these sorts of governance negotiations. In particular, civil society has been excluded from most of these EU firm-state negotiations (most clearly the case in the run-up to the Hate Speech code), and as such the public often does not know about — or have a say in — the creation of agreements that can have meaningful ramifications on their online activities (Citron, 2017; Tusikov, 2016).

The governance of online content on platforms is a far less multistakeholder undertaking than the governance of internet protocols and standards, with far fewer formalised institutions and fora. Other than the Dynamic Coalition on Platform Responsibility, a group convened through the UN Internet Governance Forum and composed of mainly academics, some firm employees, and a few government officials that has sought to create a set of “Platform-User Protections” that could serve as standards for platform Terms of Service, there have been very few informal governance initiatives that bring together all three types of actors. While multistakeholderism is no panacea, with Carr (2015) and others showing how civil society has been marginalised in ‘Internet Governance’, and merely serves to legitimise the process for other, more powerful actors, civil society has been excluded wholly from much of the contemporary content governance arena. What are the long-run implications of this trend? Future work could fruitfully examine the power relations between actors in the lead up to understudied initiatives like the EU Internet Forum and the GNI, and more closely assess the role of digital rights advocacy groups in today’s online content governance debates.

Conclusion

In the past half century, considerable scholarship from political science, law, economics, and other disciplines has been devoted to the difficult questions of corporate accountability and governance. Corporate activity has always mattered a lot in the globalised world: as Ruggie (2007, p. 830) once asked, “Does Shell’s sphere of influence in the Niger Delta not cover everything ranging from the right to health, through the right to free speech, to the rights to physical integrity and due process?” Today, companies like Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Apple have fashioned a global sphere of influence that often begs many of the same questions.

While the commitments enacted by traditional command-and-control regulation are frequently scrutinised in depth, there is a need to develop new frameworks that also consider the multiple and overlapping forms of governance that increasingly shape today’s most difficult technology policy debates. From the Christchurch Call to Facebook’s Oversight Body, non-binding principles, firm-specific regulatory initiatives, and multi-actor working groups and codes of conduct are likely to play an even larger role in coming years. As Maclay (2014, p. 70) predicted, if privacy, free expression, safety, and other important democratic values “are insufficiently protected by public regulation, society demonstrates a desire for additional regulation, and cooperation is possible across sectors that are often in tension, then new policy strategies for regulation emerge.”

Multistakeholder regulatory standards setting schemes have proliferated for other industries because they often are the best out of a slew of bad options (Gasser, Budish, & Myers West, 2015). While they can be easy to dismiss outright as “soft” or “non-binding”, the political science literature on transnational governance shows that such schemes are a vital part of the corporate regulatory toolbox, and can help us understand complex relationships of contestation and bargaining across different actor preferences. Far more work is needed to systematically assess the varying impact and outcomes of these different informal regulatory arrangements.

Acknowledgements

My sincere thanks to José van Dijck, Bernhard Rieder, Sally Wyatt, Jonas Andersson Schwarz, and Frédéric Dubois for their thoughtful editing and suggestions, and to Ian Brown, Corinne Cath, Zoë Johnson, Thomas Kadri, Anton Peez, Duncan Snidal, and Natasha Tusikov for taking the time to provide valuable comments on earlier versions of this article. Special thanks to Duncan Snidal and the Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law for permission to reproduce figures.

References

Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (2009a). Strengthening international regulation through transmittal new governance: Overcoming the orchestration deficit. Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law, 42, 501–578. Available at https://wp0.its.vanderbilt.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/78/abbott-cr_final.pdf

Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (2009b). The Governance Triangle: Regulatory Standards Institutions and the Shadow of the State. In W. Mattli & N. Woods (Eds.), The Politics of Global Regulation (pp. 44–88). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9781400830732.44

Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (2010). International Regulation without International Government: Improving IO Performance through Orchestration. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1487129

Amnesty International. (2018). Toxic Twitter [Report]. London: Amnesty International. Retrieved from https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2018/03/online-violence-against-women-chapter-1/

Andersson Schwarz, J. (2017). Platform Logic: An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Platform-Based Economy. Policy & Internet, 9(4), 374–394. doi:10.1002/poi3.159

ARTICLE 19. (2018). Self-regulation and “hate speech” on social media platforms. London: ARTICLE 19. Retrieved from https://www.article19.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Self-regulation-and-%E2%80%98hate-speech%E2%80%99-on-social-media-platforms_March2018.pdf

Baumann-Pauly, D., Nolan, J., Van Heerden, A., & Samway, M. (2017). Industry-specific multi-stakeholder initiatives that govern corporate human rights standards: Legitimacy assessments of the Fair Labor Association and the Global Network Initiative. Journal of Business Ethics, 143(4), 771–787. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3076-z

Black, J. (2001). Decentring regulation: Understanding the role of regulation and self-regulation in a “post-regulatory” world. Current Legal Problems, 54(1), 103–146. doi:10.1093/clp/54.1.103

Black, J. (2008). Constructing and contesting legitimacy and accountability in polycentric regulatory regimes. Regulation & Governance, 2(2), 137–164. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5991.2008.00034.x

Brown, I. (2013). The global online freedom act. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, 153–160. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/43134395

Bucher, T. (2018). If... Then: Algorithmic Power and Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bulkeley, H., Andonova, L., Bäckstrand, K., Betsill, M., Compagnon, D., Duffy, R., … VanDeveer, S. (2012). Governing climate change transnationally: Assessing the evidence from a database of sixty initiatives. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 30(4), 591–612. doi:10.1068/c11126

Büthe, T., & Mattli, W. (2011). The New Global Rulers: The Privatization of Regulation in the World Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9781400838790

Carr, M. (2015). Power plays in global internet governance. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 43(2), 640–659. doi:10.1177/0305829814562655

Citron, D. K. (2017). Extremist Speech, Compelled Conformity, and Censorship Creep. Notre Dame Law Review, 93(3), 1035. Retrieved from https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol93/iss3/3/

Coche, E. (2018). Privatised enforcement and the right to freedom of expression in a world confronted with terrorism propaganda online. Internet Policy Review, 7(4). doi:10.14763/2018.4.1382

Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee. (2019). Disinformation and “fake news” [Report No. 8]. London: House of Commons.

Dingwerth, K., & Pattberg, P. (2009). World politics and organizational fields: The case of transnational sustainability governance. European Journal of International Relations, 15(4), 707–743. doi:10.1177/1354066109345056

Donahoe, E., Diamond, L. Metzger, M., Rydzak, J., Pakzad, R., Zaldumbide, S. … Toh, A. (2019). Social Media Councils: From Concept to Reality [Report]. Stanford: Stanford Global Digital Policy Incubator. Retrieved from https://cyber.fsi.stanford.edu/gdpi//content/social-media-councils-concept-reality-conference-report

Douek, E. (2019). Two Calls for Tech Regulation: The French Government Report and the Christchurch Call. Lawfare. Retrieved from https://www.lawfareblog.com/two-calls-tech-regulation-french-government-report-and-christchurch-call

European Commission. (2013). Self-regulation for a Better Internet for Kids. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/self-regulation-and-stakeholders-better-internet-kids

European Commission. (2016). European Commission and IT Companies Announce Code of Conduct on Illegal Hate Speech [Press release]. Retrieved from http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-16-1937_en.htm

European Commission. (2019). Code of Practice against disinformation: Commission calls on signatories to intensify their efforts [Press release]. Retrieved from http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-19-746_en.htm

European Digital Rights initiative. (2013, January 29). RIP CleanIT [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://edri.org/rip-cleanit/

Farrell, H., & Newman, A. (2015). The New Politics of Interdependence: Cross-National Layering in Trans-Atlantic Regulatory Disputes. Comparative Political Studies, 48(4), 497–526. doi:10.1177/0010414014542330

Fiedler, K. (2016). EU Internet Forum against terrorist content and hate speech online: Document pool [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://edri.org/eu-internet-forum-document-pool/

Finck, M. (2017). Digital co-regulation: Designing a supranational legal framework for the platform economy [Working Paper No. 15/2017]. London: The London School of Economic and Political Science. Retrieved from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/87568

Fransen, L. (2012). Multi-stakeholder governance and voluntary programme interactions: Legitimation politics in the institutional design of Corporate Social Responsibility. Socio-Economic Review, 10(1), 163–192. doi:10.1093/ser/mwr029

Fransen, L. W., & Kolk, A. (2007). Global rule-setting for business: A critical analysis of multi-stakeholder standards. Organization, 14(5), 667–684. doi:10.1177/1350508407080305

Fuchs, D. A. (2007). Business power in global governance. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Gasser, U., Budish, R., & Myers West, S. (2015). Multistakeholder as Governance Groups: Observations from case studies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Berkman Center for Internet and Society.

Gillespie, T. (2010). The Politics of ’Platforms’. New Media & Society, 12(3), 347–364. doi:10.1177/1461444809342738

Goldsmith, J. L., & Wu, T. (2006). Who controls the Internet?: Illusions of a borderless world. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gorwa, R. (2019). What is platform governance? Information, Communication & Society, 22(6), 854–871. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2019.1573914

Hale, T. (2008). Transparency, Accountability, and Global Governance. Global Governance, 14, 73–94. doi:10.1163/19426720-01401006

Hale, T., Held, D., & Young, K. (2013). Gridlock: Why global cooperation is failing when we need it most. Cambridge: Polity.

Hall, R. B., & Biersteker, T. J. (2002). The Emergence of Private Authority in Global Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.7202/038685ar

Haufler, V. (2003). New forms of governance: Certification regimes as social regulations of the global market. In E. Meidinger, C. Elliott, & G. Oesten (Eds.), Social and political dimensions of forest certification (pp. 237–247). Remagen: Verlag Kessel.

Helberger, N., Pierson, J., & Poell, T. (2018). Governing online platforms: From contested to cooperative responsibility. The Information Society, 34(1), 1–14. doi:10.1080/01972243.2017.1391913

Hirsch, D. D. (2013). In Search of the Holy Grail: Achieving Global Privacy Rules Through Sector-Based Codes of Conduct. Ohio State Law Journal, 74(6), 1029–1070. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/1811/71607

Kadri, T., & Klonick, K. (2019). Facebook v. Sullivan: Building Constitutional Law for Online Speech [Research Paper No. 19-0020]. New York: St. John's University, School of Law. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3332530

Kaminski, M. E. (2015). When the default is no penalty: Negotiating privacy at the NTIA. Denver Law Review, 93, 925–949. Available at https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/970/

Kaye, D. (2018). A Human Rights Approach to Platform Content Regulation [Report]. New York: United Nations. Retrieved from https://freedex.org/a-human-rights-approach-to-platform-content-regulation/

Kaye, D. (2019). Speech Police: The Global Struggle to Govern the Internet. New York: Columbia Global Reports.

Keller, D. (2018a). Internet Platforms: Observations on Speech, Danger, and Money [Paper No. 1807]. Palo Alto: Hoover Institution. Retrieved from https://www.hoover.org/research/internet-platforms-observations-speech-danger-and-money

Keller, D. (2018b). The Right Tools: Europe’s Intermediary Liability Laws and the EU 2016 General Data Protection Regulation. Berkeley Technology Law Journal, 33(1), 287–364. doi:10.15779/Z38639K53J

Klonick, K. (2017). The new governors: The people, rules, and processes governing online speech. Harvard Law Review, 131(6), 1598–1670. Retrieved from https://harvardlawreview.org/2018/04/the-new-governors-the-people-rules-and-processes-governing-online-speech/

Kuklis, L. (2019). AVMSD and video-sharing platforms regulation: Toward a user-oriented solution? LSE Media Policy Project. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/mediapolicyproject/2019/05/28/avmsd-and-video-sharing-platforms-regulation-toward-a-user-oriented-solution/

Livingstone, S., Ólafsson, K., O’Neill, B., & Donoso, V. (2012). Towards a better internet for children: Findings and recommendations from EU Kids Online to inform the CEO coalition [Report]. London: London School of Economics and Politics Science. Retrieved from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/44213/

Livingstone, S., Ólafsson, K., & Staksrud, E. (2013). Risky Social Networking Practices Among “Underage” Users: Lessons for Evidence-Based Policy. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18(3), 303–320. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12012

Lodge, M. (2008). Regulation, the Regulatory State and European Politics. West European Politics, 31(1-2), 280–301. doi:10.1080/01402380701835074

Lynskey, O. (2017). Regulating ’Platform Power’ [Working Paper No. 1]. London: London School of Economics and Political Science, Law Department. Available at http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/73404/1/WPS2017-01_Lynskey.pdf

Maclay, C. M. (2010). Protecting privacy and expression online: Can the Global Network Initiative embrace the character of the net. In R. J. Deibert, J. Palfrey, R. Rohozinski, & J. Zittrain (Eds.), Access controlled : the shaping of power, rights, and rule in cyberspace (pp. 87–108). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. doi:10.7551/mitpress/8551.001.0001

Maclay, C. M. (2014). An improbable coalition: How businesses, non-governmental organizations, investors and academics formed the global network initiative to promote privacy and free expression online. (PhD Thesis). Northeastern University, Boston, MA. Available at https://repository.library.northeastern.edu/files/neu:336802/fulltext.pdf

Malhotra, N., Monin, B., & Tomz, M. (2019). Does Private Regulation Preempt Public Regulation? American Political Science Review, 113(1), 19–37. doi:10.1017/S0003055418000679

Marsden, C. (2018). Prosumer law and network platform regulation: The long view towards creating offdata. Georgetown Law Technology Review, 2(2), 376–398. Retrieved from https://georgetownlawtechreview.org/prosumer-law-and-network-platform-regulation-the-long-view-towards-creating-offdata/GLTR-07-2018/

Marsden, C. T. (2011). Internet co-regulation: European law, regulatory governance and legitimacy in cyberspace. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511763410

Matamoros-Fernandez, A. (2018). Platformed racism: The Adam Goodes war dance and booing controversy on twitter, YouTube, and Facebook (PhD Thesis). Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD. doi:10.5204/thesis.eprints.120573

Mikler, J. (2018). The Political Power of Global Corporations. Cambridge: Polity.

Napoli, P., & Caplan, R. (2017). Why media companies insist they’re not media companies, why they’re wrong, and why it matters. First Monday, 22(5). doi:10.5210/fm.v22i5.7051

Potoski, M., & Prakash, A. (2005). Green Clubs and Voluntary Governance: ISO 14001 and Firms’ Regulatory Compliance. American Journal of Political Science, 49(2), 235–248. doi:10.1111/j.0092-5853.2005.00120.x

Poullet, Y. (2006). EU data protection policy. The Directive 95/46/EC: Ten years after. Computer Law & Security Review, 22(3), 206–217. doi:10.1016/j.clsr.2006.03.004

Puppis, M. (2010). Media governance: A new concept for the analysis of media policy and regulation. Communication, Culture & Critique, 3(2), 134–149. doi:10.1111/j.1753-9137.2010.01063.x

Raymond, M., & DeNardis, L. (2015). Multistakeholderism: Anatomy of an inchoate global institution. International Theory, 7(3), 572–616. doi:10.1017/s1752971915000081

Risse, T. (2002). Transnational actors and world politics. In W. Carlsnaes, T. Risse, & B. Simmons (Eds.), Handbook of International Relations (pp. 255–274). London, UK: SAGE. doi:10.4135/9781848608290.n13

Roberts, S. (2018). Digital detritus: ’Error’ and the logic of opacity in social media content moderation. First Monday, 23(3). doi:10.5210/fm.v23i3.8283

Rubinstein, I. (2018). The Future of Self-Regulation is Co-Regulation. In E. Selinger, J. Polonetsky, & O. Tene (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Consumer Privacy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316831960

Ruggie, J. G. (2007). Business and human rights: The evolving international agenda. American Journal of International Law, 101(4), 819–840. doi:10.1017/S0002930000037738

Schulz, W. (2018). Regulating Intermediaries to Protect Privacy Online: The Case of the German NetzDG [Discussion Paper No. 2018-01]. Berlin: Alexander von Humboldt Institut für Internet und Gesellschaft. Available at https://www.hiig.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/SSRN-id3216572.pdf

Senden, L. (2005). Soft law, self-regulation and co-regulation in European law: Where do they meet? Electronic Journal of Comparative Law, 9(1). Retrieved from https://www.ejcl.org/91/art91-3.PDF

Sikkink, K. (1986). Codes of conduct for transnational corporations: The case of the WHO/UNICEF code. International Organization, 40(4), 815–840. doi:10.1017/S0020818300027387

Simpson, S. S. (2002). Corporate crime, law, and social control. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stepanovich, A., & Mitnick, D. (2015). Universal Implementation Guide for the International Principles on the Application of Human Rights to Communication Surveillance. New York: Access Now. Retrieved from https://necessaryandproportionate.org/files/2016/04/01/implementation_guide_international_principles_2015.pdf

Strange, S. (1991). Big Business and the State. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 20(2), 245–250. doi:10.1177/03058298910200021501

Tusikov, N. (2016). Chokepoints: Global private regulation on the Internet. Oakland: University of California Press. doi:10.1525/california/9780520291218.001.0001

Tusikov, N. (2017). Transnational non-state regulatory regimes. In P. Drahos (Ed.), Regulatory Theory: Foundations and Applications (pp. 339–353). Canberra: ANU Press. doi:10.22459/RT.02.2017.20

Twitter Public Policy. (2017). Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/company/2017/Global-Internet-Forum-to-Counter-Terrorism.html

Vernon, R. (1977). Storm over the multinationals: The real issues. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Vogel, D. (2010). The private regulation of global corporate conduct: Achievements and limitations. Business & Society, 49(1), 68–87. doi:10.1177/0007650309343407

Wagner, B. (2013). Governing Internet Expression: How public and private regulation shape expression governance. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 10(4), 389–403. doi:10.1080/19331681.2013.799051

Wagner, B. (2016). Global Free Expression - Governing the Boundaries of Internet Content. Cham: Springer.

Zittrain, J. (2008). The future of the Internet and how to stop it. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Zuckerberg, M. (2018). A Blueprint for Content Governance and Enforcement. Retrived from https://www.facebook.com/notes/mark-zuckerberg/a-blueprint-for-content-governance-and-enforcement/10156443129621634/

Footnotes

1. I use platform in this article despite its analytical challenges (e.g., its often unhelpful grouping of many different services and business models, ranging from social networking to online shopping and homes-haring) to clearly demarcate that this article is focused on a narrow set of global technology corporations, and therefore excludes companies such as telecommunications providers, most hardware manufacturers, or other intermediaries. In particular, I focus here on the platforms that can be conceptualised as private infrastructures for online expression.

2. In this article, I understand the EU as a state actor, following in the tradition of scholarship on European regulation that looks at the EU “regulatory state” as a discrete entity (Lodge, 2008). While Farrell and Newman (2015, p. 520) note that this has been matter of some debate, and “there are complex relations between the EU level and the politics of its individual member states, the EU level is important for most areas of regulation and considered as a polity”.

3. The GNI principles, implementation guidelines, and accountability framework are available at: globalnetworkinitiative.org.

Add new comment