Political microtargeting: Towards a pragmatic approach

Abstract

It has become increasingly popular for scholars to investigate the technology of political, personal microtargeting (PMT). We review a sample of 62 research articles in the field of political PMT and argue that these studies can be grouped according to different orientations: an interpretative orientation, either expressing hopes for voter mobilisation or strong concerns for democracy and voter manipulation, or a descriptive orientation, viewing PMT as a supplement to the traditional elements of political campaigns. We argue that these two orientations must continuously be mixed thoughtfully in a pragmatic approach that addresses public concerns on highly empirical grounds to avoid technological myths.Introduction

Social media (SoMe) has become an integrated element of most political campaigning. Politicians have acquired increasingly effective tools to ‘microtarget’ voters, which has resulted in a growing academic focus on the controversial manipulative influence of digitalised political campaigns. For 20 years, scholars have studied the tools of digital political campaigning in disciplines ranging from marketing and communication studies to political science. Recently, there has been an increase in academic interest in the manipulative effects of these new tools (Baldwin-Philippi, 2019). This review seeks to investigate existing research on personal microtargeting (PMT). We argue for a need to recap and examine how the study of the phenomenon has developed, how the academic field is structured and especially how the field of research has addressed the growing public concerns. According to Baldwin-Philippi (2019), current imaginaries of digital political campaign tools encompass both the hopes and fears of how digital technology will shape politics and democracy. We aim to study if these imaginaries can also be found in research in the scientific literature on PMT. We do so by categorising key contributions to the field from 2006‒2022 as either interpretative (expressing either hopes for voter mobilisation or strong concerns for democracy and voter manipulation) or as descriptive, viewing PMT as a supplement to the traditional elements of political campaigns.

Our paper is a semi-systematic review of the academic political PMT literature. We therefore seek to investigate how the research field of political PMT has evolved. This research question is examined in two steps. First, we examine the PMT field by mapping the themes in the existing literature. Second, we examine and categorise the type of study in the publications to see how public concern of PMT is addressed in the literature. Our purpose is not to clarify if public concerns of PMT are justified, but merely to clarify if the academic literature thoroughly addresses the concerns.

The next section presents our analytical strategy for the review. After a methodological section, we present the sample of the publications we have collected. We provide insight on the influence of the 2016 Cambridge Analytica (CA) scandal on the balance of descriptive and interpretative studies by dividing the publications we found into different orientations: interpretative (both positive and negative), descriptive and a mix of interpretative/descriptive. We find clear connections between the orientation and type of study in the publication. Finally, we argue for a stronger, pragmatic approach between the two orientations, combining research in public concerns for PMT with empirical studies, and our closing discussion on the future direction of the field of study highlights further gaps detected in the sample.

Background

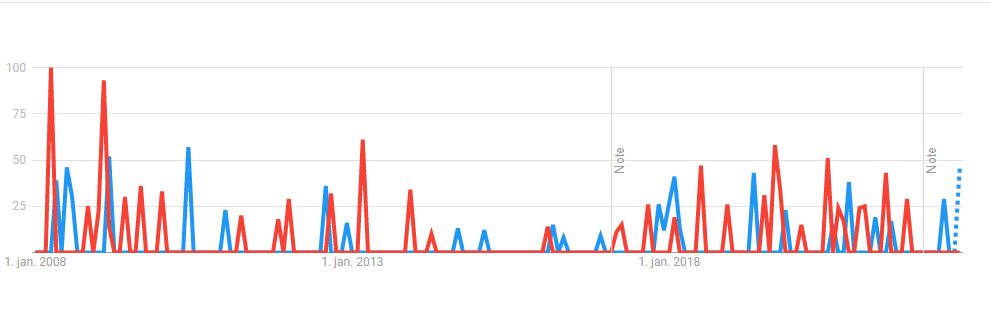

Political campaigning has moved into a new phase in which digital technology is used to launch the sophisticated microtargeting of segmented groups of voters, donors and supporters (Bennett, 2015; Bimber, 2014; Cacciotto, 2017; Holtzhausen, 2016; Nickerson & Rogers, 2014). Social monitoring companies (e.g., IBM, Meltwater) now offer to assist politicians to target voters based on psychometrics (psychological measurement). These data sets are applied in modern political communication to set the agenda and mobilise voters using PMT technology. This development has generated significant attention, especially related to presidential election campaigns in the US. The US presidential campaigns in 2008, 2012 and 2016 introduced the use of digital campaigning. This is especially true of the big data consultants for the 2016 Trump Campaign, the British firm Cambridge Analytica, who received enormous press coverage (Cadwalladr, 2018; Lapowsky, 2017). To indicate the importance of the events in 2016, a simple Google Trends news search for the term ‘political microtargeting’ (see Figure 1) compared to the term ‘digital political campaign’ indicates an increase in the public interest and awareness of the phenomenon since 2016.

Early increases in interest can be explained by the Howard Dean’s campaign in 2004 and Barack Obama’s 2008 and 2012 election campaigns. The dramatic increase in public interest in 2016 can be explained by the Trump campaign together with the CA/Facebook-scandal. These events have publicly highlighted the ability of political actors to monitor the online behavioural patterns of individual citizens ‒ and not least to subsequently tailor messages to them. We therefore seek to address whether the public concerns after 2016 also affected the scientific literature on data-driven campaigning.

Baldwin-Philippi (2019) discusses this increased interest in digitalised political campaign tools as expressions of ‘data-imaginaries’ that encompass counter-positions of both the hopes and fears of how digital technology will shape politics and democracy. The hope imaginaries are grounded by faith in enhanced networked, deliberative power symmetry, accompanied by a vision of digitalisation and SoMe used to increase the bottom-up mobilisation of citizens in political issues. #MeToo represents a profound example of this vision. The fear imaginaries are spurred by the NSA spying scandal in 2013 and the Facebook scandal in 2018. However, the scientific discourse on the subject also communicates hopes and fears. According to Lilleker (2016, p. 237), most studies find that SoMe has improved the interactivity of campaigns with their followers, adding a stronger deliberative element. Other scholars argue that digital political campaign tools create a danger for surveillance and the violation of privacy rights (Holtzhausen, 2016, p. 33), and that it may create a shift towards hyper-management and control of citizens (Bimber, 2014) through PMT manipulation. Our purpose is to map the scientific discourse on these matters by categorising key contributions to the field from 2005‒2022 as either descriptive in their assessment of modern political campaigns, or as interpretative. We take a normative stance, stretching either the deliberative potential of digitalised political campaigns or critically stretching the manipulative risk associated with political PMT. To specify, we primarily focus on the literature dealing with tools in digitalised political campaigns and argue that elements of the descriptive and interpretative orientations can be combined in the same publication, which we see as a third category.

Method and analytical strategy

To investigate the academic field of political PMT thoroughly, we adopt a semi-systematic approach that synthesises argumentative, integrative and historical approaches (Snyder, 2019). These approaches are included to ensure a thorough review encapsulating the complexity of the field. The historical review focuses on how the field has developed chronologically. We limited the search to 2006‒2022. The year 2006 is partly chosen to give a full range of time, since digital tools were introduced to political campaigning by Dean in 2004, and partly to gain a sufficient timespan on both sides of 2016. In the integrative overview, it is important to detect the themes and topics in the literature. We detect the topics in an explorative coding of the articles and classify the publications in our sample with respect to three different themes:

- Communicative context (CC), which encompasses issues of communication surrounding political PMT, such as strategy, hybrid media system or the digital transformation of the media system.

- Political context (P), which encompasses political issues surrounding political PMT, such as voter behaviour, law (GDPR, privacy) and/or the importance of national political culture.

- PMT technique in focus (M), which encompasses PMT-focused technological issues, such as new technological developments or the efficiency of PMT techniques.

The argumentative approach focuses on the constraints in the literature (Davis et al., 2014) and investigates the different orientations in it. To begin with, the academic literature addressing political PMT cannot be structured by using the same positions found in the broader societal data imaginaries of both hopes and fears for how digital technology shapes politics and democracy (see Baldwin-Phillippi, 2019). To have a more adequate categorisation of the field, we adopt:

- A descriptive orientation, where PMTs are viewed merely as a new tool in the digital campaigning toolbox.

- An interpretative orientation including both positive (hope) and negative (fear) assessments of PMT.

- An orientation where the elements of the descriptive and interpretative orientations are combined in the same publication.

We will also explore differences in the types of study used in publications with different orientations to see if their respective arguments are based on empirical grounds, especially when it comes to addressing public concerns. Our analytical strategy is summarised in Table 1 below.

|

Element |

Central question |

|

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Historical |

How does the field develop before and after 2016? |

|

2 |

Integrative |

What themes are addressed before and after 2016? |

|

3 |

Argumentative |

What orientations (descriptive/interpretative (neg. vs. pos.)) do publications have before and after 2016? |

We accessed Web of Science and searched for the following term: ‘microtargeting’, as part of the topic (title, abstract, keywords), in the period 2006‒2022 (the search produced very few hits before 2006). Though 2022 is an incomplete year at the time of research, we included three articles from 2022 to gain as many articles as possible (in consequence, the incompleteness of 2022 is a minor bias in our results, though it does not change our main conclusions). The result of our search was a 99-article sample. From this sample, we only included articles related to the categories Political Science, Communication, Law, Computer Science Information Systems and Social Sciences Interdisciplinary. Overall, the most articles were in the field of Political Science (24), Communication (19) and Law (9). The excluded articles were related to very different disciplines (e.g., marketing, neurosurgery, bioresearch). A further assessment of each publication found eight articles not relevant to our topic. Furthermore, we could not find or access six publications listed in the sample. The result was a revised list of 33 articles. To this list we added 29 relevant research publications we knew of or found using Google Scholar (chapters from edited volumes, for example). These publications were not found on the Web of Science. Our final sample encompasses 62 publications. We cannot claim that this sample of articles is exhaustive when it comes to research investigating political PMT, since related search terms like ‘big data’, ‘data-driven campaign’ etc. are not included in the sample. However, we will argue that the inclusion of all relevant articles in the Web of Science sample secure a high degree of representation of the possible orientations in the field regarding time, themes, topics and types of study.

Findings and framing the body of literature

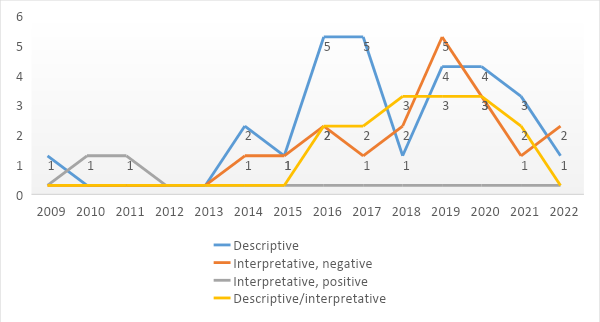

Table 2 (see Appendix) categorises the publications in our sample with respect to year, theme, topics and position (interpretative vs. descriptive). As Figure 2 shows, the number of publications is increasing over time, albeit with a decline in recent years (even if you disregard the incomplete year of 2022). The clear majority of the publications have been published since 2016, which indicates how the increased public interest since 2016 (see above) is also reflected by an increase in research interest in the field. Many of these publications mention the CA scandal and its role in the US16 election, indicating that the 2016 events drove the boom in the literature.

Integrative: What themes and topics are addressed before and after 2016?

Twenty-one publications focus on the communication context of PMT, five of which focus on the (efficiency of) campaign strategy (Aagaard, 2019; Cacciatore et al., 2016; Lilleker, 2016; Panagopoulos, 2016; Solovey, 2017). Five further publications deal with the communicative context in relation to the effects and efficiency of political PMT (Baldwin-Philippi, 2019; Burge et al., 2020; Cacciotto, 2017; Endres & Kelly, 2018; Haenschen & Jennings, 2019).

The political context of PMT is the most common theme in the sample, encompassing 30 publications in total. Among the topics in this theme are the regulation of political PMT. Ten of the 30 publications deal with different aspects regulating political PMT (GDPR, privacy, etc.) (Bennett, 2016; Bodó et al., 2017; Zuiderveen Borgesius et al., 2018; Chester & Montgomery, 2019; Hu, 2020; Nenadić, 2019; Rhum, 2021; Rubinstein, 2014). Another important topic in this theme is national political culture as a variable in the use of political PMT during a campaign. While many of the publications related to the political context theme deal with US conditions, a range of publications also study experiences from other countries. Eight publications in total focus on national cultural experiences (Anstead, 2017; Dobber et al., 2017; Dommett & Power, 2019; Jungherr, 2016; Kruschinski & Haller, 2017; Medina Serrano et al., 2020; Papakyriakopoulos et al., 2018; Patten, 2017). Two of them (Dobber et al., 2017; Nenadić, 2019) investigate the European approach, especially the GDPR-framework for political PMT. Bayer (2020) addresses PMTs as violations of human rights. Hu (2020) focuses mainly on the solutions for US data protection in the light of the CA scandal, arguing that the Federal Trade Commission is not doing enough to protect data. Two publications (Bennett, 2016; Dobber et al., 2017) have a profound comparative focus. At least nine of the publications examine European conditions: Anstead (2017) and Dommett and Power (2019) investigate the British case, Dobber et al. (2017) study Dutch experiences, while Jungherr (2016), Kruschinski and Haller (2017) and Serrano et al. (2020) investigate the German case. Many of the publications related to the political context theme are interpretative (negative). We address this issue in the next section.

As Figure 3 illustrates, many of the publications focusing on the political context of PMT were published in or after 2016, which again indicates increased public concern (privacy issues, political manipulation) for the negative effects of political PMT. In contrast, an example of a pre-2016 contribution is Bennett (2015), who addresses digital transformation, arguing that digital surveillance might even reinforce democracy, since politicians can more easily mobilise voters if they know their preferences. Again, this indicates a shift in the literature in light of the Trump 2016 victory.

Eleven publications investigate technology related to PMT or the efficiency of PMT. One example is Dobber et al. (2021), who investigates the effects of political PMT using so-called deepfakes on voters. While publications dealing with the communicative and political context seem to decline again in 2021, publications studying the efficiency of the political PMT technology seem to be increasing. This development could possibly indicate a new stream of research literature dealing much more with the technological capabilities behind political PMT.

Argumentative: What orientations can be found before and after 2016?

Next, we have categorised the publications as descriptive, interpretative (negative or positive) or a mix of both. An ‘interpretative’ categorisation indicates that the publication either expresses negative beliefs based on democratic concerns or, conversely, expresses positive deliberative democratic hope regarding political PMT. In contrast, categorisation as ‘descriptive’ indicates that the publication overtly tends to see political PMT as (just) a new tool that can help improve the analytical basis for digital campaigning. It is also possible to categorise the publication in the middle, containing a balance or mix of both descriptive and interpretative elements (again, either containing positive or negative orientations).

What different orientations can be found?

As shown in Figure 4, aside from interpretative positive, there is a clear increase in all types of orientations. Firstly, we see a rise in more descriptive publications in 2016 (mainly publications detecting and describing the phenomenon) and then a rise in both interpretative (negative) publications and those containing both descriptive/interpretative elements. Both of these categories consist of publications that are critical towards the consequences of political PMT and take public concerns into account.

Interpretative publications

Twenty publications in the sample can be categorised as interpretative, only two of which are positive (Murray & Scime, 2010; Nielsen, 2011), both predating 2016. As indicated above, most of the interpretative publications (14) are from after 2016, again indicating a critical turn in the literature after the CA/Facebook scandal. The rise of interpretative (negative) publications culminates in 2019. Many of these studies focus on voter surveillance and privacy issues. Gorton (2016) emphasises how politicians can manipulate voters using PMT technologies. Holtzhausen (2016) addresses the potential threats of big data, arguing that its use in political communication can have harmful effects on democracy due to discriminatory effects toward different voter groups. Hegazy (2019) addresses the concern with and need for the regulation of big data; he argues that the Trump 2016 SoMe strategy was a game changer for political campaigns. Burkell and Regan (2019) reinforce these arguments in their essay, arguing that PMT can undermine voter autonomy and manipulate voters, since it can activate unconscious biases and impact voter preferences without them noticing. Chester and Montgomery (2017) also argue that the use of big data in campaigns is highly manipulative, since voters are not informed about the mechanisms behind PMT. Susser et al. (2019) emphasise how PMT can undermine voter autonomy and argue that voters must be aware of marketing tools to minimise online manipulation. Kusche (2020) compares political clientelism and data-field campaigning in a theoretical paper, which argues that while personalised, data-driven campaigns can mobilise marginalised voters, personalised political content can at the same time detach voters from potential collectives and communities. Bayer (2020) stresses the conflict between political PMT and voter rights, arguing that PMT is incompatible with the right to receive information.

Descriptive publications

Twenty-seven publications in our sample are categorised with a descriptive orientation, with a clear increase of publications in 2016 to 2020 (and then apparently a decline in 2021). In general, these studies perceive PMT more as just another tool in the political campaigning toolbox than as a game changer for political campaigning. Four descriptive studies were published prior to 2016; two are essays, one is a quantitative study, and one is a review. Bimber (2014) discusses the different effects of data-driven campaigns. He also focuses on the possibility for politicians to create a network with their potential voters and for donors to donate to politicians. Similarly, Nickerson and Rogers (2014) argue in an essay that, despite electoral benefits, data-driven campaigns have limited significance and that digital tools do not change the nature of political campaigns. Bennett (2015) theoretically examines voter surveillance, arguing that it is present in political campaigns and might transform how political campaigns are conducted. Vergeer (2015) reviews different studies that have examined Twitter as a tool for politicians and concludes that Twitter is more popular during election periods than otherwise.

Eighteen of the descriptive publications are published after 2016. Both theoretical and empirical studies are prevalent. Bodó et al. (2017) presents elements surrounding PMT that require further attention; they highlight the need for a non-US focus in the literature, since national context can play a crucial role, and they argue that comparative research is much needed. Cacciotto (2017) highlights how the popularity of digitalised politics in the US will also become increasingly popular in Europe and South America. Dobber et al. (2017) investigate the extent to which campaigners in the Netherlands use PMT strategies, based on 11 interviews with campaign leaders. The study investigates the 2017 Dutch election as a case, concluding that parties in proportional representation systems can also use PMT as a campaign tool. Baldwin-Philippi (2019) reviews the societal imaginaries in the light of Trump 2016. Somewhat similarly, Aagaard (2019) also describes the use of big data in Trump 2016, arguing that big data can be an effective tool for politicians, although other factors, such as the audience and candidates, remain relevant. However, Aagaard (2019) also emphasises that the use of big data can conflict with democratic values. Benkler et al. (2020) use quantitative data, arguing that the effective spread of Trump’s misinformation could be ascribed to his position as president and therefore his privileged position in the mass media coupled together with his SoMe use.

Interpretative-descriptive publications

While 47 of the publications in the sample can be categorised in the more extreme orientations of interpretative or descriptive, 15 publications contain both interpretative and descriptive elements in their approach to PMT. However, the interpretative element in these publications always leans towards a negative view of PMT. The interpretative-descriptive studies vary in their topics. One focus of the publications emphasise the effects and efficiency of PMTs (Lavigne, 2021). Two of the studies focus on legal issues (e.g., GDPR, privacy). Dobber et al. (2019) examine GDPR and PMT regulations in Europe. Zuiderveen Borgesius et al. (2018) focus on privacy issues related to campaign strategy. Four of the publications encompass experiences from specific countries (Anstead, 2017; Dobber et al., 2019; Dommett & Power, 2019; Papakyriakopoulos et al., 2018; Patten, 2017).

Thirteen of the 15 interpretative-descriptive publications are written after 2016, nine of which are empirical studies. Again, this indicates an increase in research interest after 2016 on both empirical grounds and with interpretative (negative) orientations. Ten of the fifteen publications are empirical studies, some of which do in fact address public concerns regarding the manipulative effect of PMT on citizens. One example is Anstead (2017), who interviewed more than 30 political practitioners to investigate data-driven campaigning in the UK and found that not all parties have the same options for data-driven campaigns. Another example is Owen (2018), who argues that digital technology changes the media campaign environment and that the ‘new media’ are changing elections fundamentally by influencing media coverage and voter behaviour. Yet another example is Dommett and Power (2019), who accommodate concerns with the lack of transparency in digitalised political marketing and investigate transparency in political advertising on Facebook in the UK, arguing that British campaign rules do not ensure voter transparency.

To sum up, the categorisation shows that our sample does in fact contain clusters of publications that are highly interpretative (the vast majority are negative) or descriptive. The interpretative publications, many of which are published after 2016, focus on the negative impact of PMTs on voters and the erosion of democracy. The descriptive publications focus more on the general digitalised transformation of political communication. The sample also contains 15 publications containing both interpretative and descriptive elements, all published in 2016 or later. In fact, the mixed interpretative-descriptive orientation in our sample is significant, which points to a more pragmatic approach to the field of study, where public concerns are addressed.

What types of studies can be found in the different orientations?

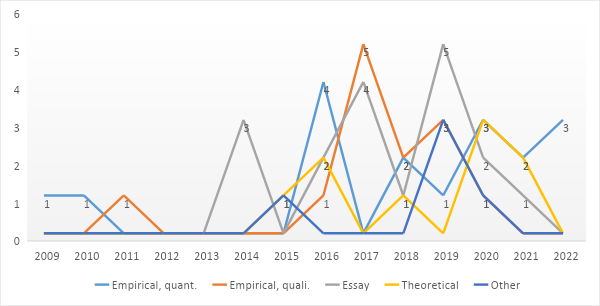

We have also categorised the publications regarding the type of study (essay, theory, empirical (quant./qual. and other (reviews, field experiments etc.). As Figure 5 shows, there is an increase in all types of studies after 2016 (also pre-2016, when it comes to essays), although there is less of an increase in theoretical publications. There is also a decline in all types of studies in recent years, but to a lesser degree in empirical, quantitative studies. The introduction of the Facebook Ad library (current version since May 2018) may very well have had an impact on the growth of quantitative studies. Several of the publications refer to or use data from the Ad library.

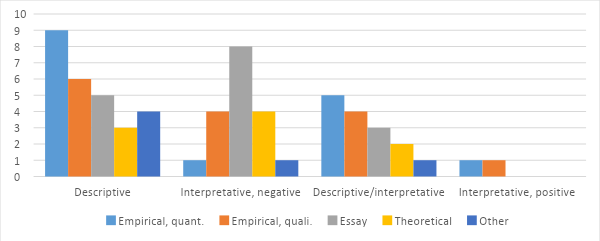

As Figure 6 clearly shows, researchers do different types of study depending on the orientation of their publication. Descriptive oriented publications tend to be based on empirical studies (both quantitative and qualitative) compared to especially interpretative, negative oriented publications. Fifteen (of 27) descriptive publications are empirical, nine of which are quantitative and six are qualitative. Of the 20 interpretative publications, eight are essays and four are theoretical developments of the field, while only five are empirical. This distribution indicates that there is a link between type of study and orientation of publication; when it comes to descriptive/interpretative publications, nine (of 15) are empirical (5 quantitative, 4 qualitative) publications. Again, this distribution indicates a link between type of study and orientation of publication.

To sum up, the two orientations of descriptive and interpretative publications also tend to be associated with different types of studies. Of the 20 interpretative publications, 12 are either essays or theoretical developments of the field, 14 of which are published after 2016. Of the 27 descriptive publications, only eight are essays or theoretical papers, while 15 are empirical studies (9 quantitative, 6 qualitative). In line with the increase in research interest, only four of the descriptive publications are published before 2016. Furthermore, nine of the 15 publications categorised as a mix of interpretative-descriptive orientation address public concerns on empirical grounds. So, overall, the general tendency in the sample is that the more descriptive the orientation, the more likely it is that the publication is based on empirical (especially quantitative) research, but the less it may take public concerns into account.

Conclusions

Our review is based on a narrow sample of PMT publications, which limits our ability to generalise with the much broader field of digital political campaign literature. However, we believe we detect important tendencies in the field of PMT research. Our findings reveal the clear tendencies of different types of studies depending on the orientation the publication takes. The descriptive approach contains more empirical research than the critical one, which contains a high number of philosophical and theoretical essays. The more descriptive the orientation, the more likely it is that the publication is based on an empirical (especially quantitative) research design, but the less it takes public concerns into account. In that sense, it could be argued that the PMT research field does not address public concerns on profound empirical grounds. However, the PMT literature does in fact encompass a more pragmatic approach to the subject that takes public concerns into account and does so on a rather empirical basis. While 10 of the 15 interpretative-descriptive publications are based on empirical evidence, the interpretative-descriptive publications tend to be declining in recent years (the year 2022 is incomplete). This decline suggests that a need remains to take public concerns into account in an interpretative-descriptive research design that encompasses (especially quantitative) empirical data.

|

Element of review |

Central question |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Historical |

How does the field develop before and after 2016? |

There is a surge in publications after 2016 and a decrease in recent years. |

|

2 |

Integrative |

What themes and topics are addressed before and after 2016? |

Few publications before 2016, mainly focusing on the communication context. After 2016, privacy, legislation and voter manipulation become dominant topics. Later, the efficiency of PMT becomes an important topic. |

|

3 |

Argumentative |

What orientations (interpretative/descriptive) are addressed before and after 2016? |

There is an increase in publications, with both descriptive and interpretative (negative) orientations as well a mix of descriptive-interpretative (negative) after 2016. There seems to be a connection between orientation and type of study; the more descriptive: the more empirical; whereas the more interpretative: the more theoretical or essayistic. |

Our review generally reveals a continued need for collaboration across the aisle between the more theoretical essays raising concerns for the public (and the more empirical) demarcated studies that can confirm or dismiss concerns regarding voter manipulation and democracy (cf. Table 3). Future research should explore such a pragmatic approach more thoroughly. We are aware that this may be difficult, however, due to the lack of transparency among the digital platforms that political campaigns often use. Our review also indicates that new tools, such as Facebook’s Crowdtangle and the Ad library, may push a new era of efficiency studies, but to address public concerns on empirical grounds, scholars may need to base their research on more experimental research if digital platforms are not made more transparent.

Although our sample is limited, Table 2 indicates that there might be a range of additional political communication topics that are not covered sufficiently in the field of research and should be explored further. Topics that are scarcely mentioned in the sample include research into the impact of PMT on voters, comparative research, automation and the persuasion effect of digital tools other than social media. Our sample contains limited research investigating the effect on voters, such as voter perception of PMT and the impact on voter behaviour. A limited number of articles (6) in the sample empirically investigate the impact on voter behaviour (Burge et al., 2020; Endres & Kelly, 2018; Haenschen, 2022; Haenschen & Jennings, 2019; Lavigne, 2021; Zarouali et al., 2020). This might be explained by our search criteria. There is a growing literature on voting and political behaviour in the digital age (see, e.g., Rogers et al., 2013), which is obviously not caught by our sample. However, the result still indicates a limited degree of congruence between digital campaign literature and voter behaviour.

A range of topics seem to attract little or no coverage in the publications included in our sample. When it comes to additional political campaign types, there is no link to research in negative campaigning or permanent campaigning (Norris & Reif, 1997), nor is there any link to research investigating how other types of political actors use digital campaign tools. While the focus in our sample of publications is almost exclusively on political parties, it must be noted that organised interests, social movements, NGOs, state agencies and public affairs departments in private companies are all also capable of engaging in PMT campaigning.

References

Aagaard, P. (2019). Big data in political communication. In J. Pedersen & A. Wilkinson, Big data. Promise, application and pitfalls (pp. 325–347). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788112352.00020

Anstead, N. (2017). Data-driven campaigning in the 2015 United Kingdom general election. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 22(3), 294–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161217706163

Baldwin-Philippi, J. (2019). Data campaigning: Between empirics and assumptions. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1437

Bayer, J. (2020). Double harm to voters: Data-driven micro-targeting and democratic public discourse. Internet Policy Review, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.1.1460

Benkler, Y., Tilton, C., Etling, B., Roberts, H., Clark, J., Faris, R., Kaiser, J., & Schmitt, C. (2020). Mail-in voter fraud: Anatomy of a disinformation campaign. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–48. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3703701

Bennett, C. J. (2015). Trends in voter surveillance in Western societies: Privacy intrusions and democratic implications. Surveillance & Society, 13(3/4), 370–384. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v13i3/4.5373

Bennett, C. J. (2016). Voter databases, micro-targeting, and data protection law: Can political parties campaign in Europe as they do in North America? International Data Privacy Law, 6(4), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1093/idpl/ipw021

Bimber, B. (2014). Digital Media in the Obama campaigns of 2008 and 2012: Adaptation to the personalized political communication environment. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 11(2), 130–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2014.895691

Bodó, B., Helberger, N., & de Vreese, C. H. (2017). Political micro-targeting: A Manchurian candidate or just a dark horse? Internet Policy Review, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2017.4.776

Burge, C. D., Wamble, J. J., & Laird, C. N. (2020). Missing the mark? An exploration of targeted campaign advertising’s effect on Black political engagement. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 8(2), 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2020.1757807

Burkell, J., & Regan, P. M. (2019). Voter preferences, voter manipulation, voter analytics: Policy options for less surveillance and more autonomy. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1438

Cacciatore, M. A., Scheufele, D. A., & Iyengar, S. (2016). The end of framing as we know it…and the future of media effects. Mass Communication and Society, 19(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2015.1068811

Cacciotto, M. M. (2017). Is political consulting going digital? Journal of Political Marketing, 16(1), 50–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2016.1262224

Cadwalladr, C. (2018, March 18). "I made Steve Bannon’s psychological warfare tool”: Meet the data war whistleblower. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/17/data-war-whistleblower-christopher-wylie-faceook-nix-bannon-trump

Chester, J., & Montgomery, K. C. (2017). The role of digital marketing in political campaigns. Internet Policy Review, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2017.4.773

Chester, J., & Montgomery, K. C. (2019). The digital commercialisation of US politics—2020 and beyond. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1443

Davis, J., Mengersen, K., Bennett, S., & Mazerolle, L. (2014). Viewing systematic reviews and meta-analysis in social research through different lenses. SpringerPlus, 3(511), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-3-511

Dobber, T., Metoui, N., Trilling, D., Helberger, N., & de Vreese, C. (2021). Do (microtargeted) deepfakes have real effects on political attitudes? The International Journal of Press/Politics, 26(1), 69–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220944364

Dobber, T., Ó Fathaigh, R., & Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. J. (2019). The regulation of online political micro-targeting in Europe. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1440

Dobber, T., Trilling, D., Helberger, N., & de Vreese, C. H. (2017). Two crates of beer and 40 pizzas: The adoption of innovative political behavioural targeting techniques. Internet Policy Review, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2017.4.777

Dommett, K., & Power, S. (2019). The political economy of Facebook advertising: Election spending, regulation and targeting online. The Political Quarterly, 90(2), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12687

Endres, K., & Kelly, K. J. (2018). Does microtargeting matter? Campaign contact strategies and young voters. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 28(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2017.1378222

Haenschen, K. (2022). The conditional effects of microtargeted Facebook advertisements on voter turnout. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09781-7

Haenschen, K., & Jennings, J. (2019). Mobilizing millennial voters with targeted internet advertisements: A field experiment. Political Communication, 36(3), 357–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2018.1548530

Hegazy, I. M. (2019). The effect of political neuromarketing 2.0 on election outcomes: The case of Trump’s presidential campaign 2016. Review of Economics and Political Science, 6(3), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1108/REPS-06-2019-0090

Holtzhausen, D. (2016). Datafication: Threat or opportunity for communication in the public sphere? Journal of Communication Management, 20(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-12-2014-0082

Hu, M. (2020). Cambridge Analytica’s black box. Big Data & Society, 7(2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720938091

Jungherr, A. (2016). Four functions of digital tools in election campaigns: The German case. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 21(3), 358–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161216642597

Kruschinski, S., & Haller, A. (2017). Restrictions on data-driven political micro-targeting in Germany. Internet Policy Review, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2017.4.780

Kusche, I. (2020). The old in the new: Voter surveillance in political clientelism and datafied campaigning. Big Data & Society, 7(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720908290

Lapowsky, I. (2017, January 16). Trump’s data firm snags RNC tech guru Darren Bolding. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2017/01/trumps-data-firm-snags-republican-national-committee-cto/

Lavigne, M. (2021). Strengthening ties: The influence of microtargeting on partisan attitudes and the vote. Party Politics, 27(5), 965–976. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820918387

Lilleker, D. G. (2016). Comparing online campaigning: The evolution of interactive campaigning from Royal to Obama to Hollande. French Politics, 14(2), 234–253. https://doi.org/10.1057/fp.2016.5

Medina Serrano, J. C., Papakyriakopoulos, O., & Hegelich, S. (2020). Exploring political ad libraries for online advertising transparency: Lessons from Germany and the 2019 European Elections. Proceedings of SMSociety’20: International Conference on Social Media and Society, 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1145/3400806.3400820

Murray, G., & Scime, A. (2010). Microtargeting and electorate segmentation: Data mining the American national election studies. Journal of Political Marketing, 9(3), 143–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2010.497732

Nenadić, I. (2019). Unpacking the “European approach” to tackling challenges of disinformation and political manipulation. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1436

Nickerson, D. W., & Rogers, T. (2014). Political campaigns and big data. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(2), 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.28.2.51

Nielsen, R. K. (2011). Mundane internet tools, mobilizing practices, and the coproduction of citizenship in political campaigns. New Media & Society, 13(5), 755–771. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810380863

Norris, P., & Reif, K. (1997). Second-order elections. European Journal of Political Research, 31(1), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00308

Owen, D. (2018). New media and political campaigns. In K. Kenski & K. Hall Jamieson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political communication (pp. 823–836). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199793471.013.016

Panagopoulos, C. (2016). All about that base: Changing campaign strategies in U.S. Presidential elections. Party Politics, 22(2), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815605676

Papakyriakopoulos, O., Hegelich, S., Shahrezaye, M., & Serrano, J. C. M. (2018). Social media and microtargeting: Political data processing and the consequences for Germany. Big Data & Society, 5(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951718811844

Patten, S. (2017). Databases, microtargeting, and the permanent campaign: A threat to democracy? In A. Marland, T. Giasson, & A. Lennox Esselment (Eds.), Permanent campaigning in Canada (pp. 47–66). University of British Columbia Press.

Rhum, K. (2021). Information fiduciaries and political microtargeting: A legal framework for regulating political advertising on digital platforms. Northwestern University Law Review, 115(6), 1829–1873.

Rogers, T., Fox, C. R., & Gerber, A. S. (2013). Rethinking why people vote. Voting as dynamic social expression. In E. Shafir (Ed.), The behavioral foundations of public policy (pp. 91–107). Princeton University Press.

Rubinstein, I. S. (2014). Voter privacy in the age of big data. Wisconsin Law Review, 861–936.

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

Solovey, V. D. (2017). Digital mythology and Donald Trump electoral campaign. Polis. Political Studies, 5, 122–132. https://doi.org/10.17976/jpps/2017.05.09

Susser, D., Roessler, B., & Nissenbaum, H. (2019). Technology, autonomy, and manipulation. Internet Policy Review, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.2.1410

Vergeer, M. (2015). Twitter and political campaigning. Sociology Compass, 9(9), 745–760. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12294

Zarouali, B., Dobber, T., De Pauw, G., & de Vreese, C. (2020). Using a personality-profiling algorithm to investigate political microtargeting: Assessing the persuasion effects of personality-tailored ads on social media. Communication Research, 49(8), 1066–1091. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220961965

Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. J., Möller, J., Kruikemeier, S., Ó Fathaigh, R., Irion, K., Dobber, T., Bodó, B., & De Vreese, C. (2018). Online political microtargeting: Promises and threats for democracy. Utrecht Law Review, 14(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.18352/ulr.420

Appendix

|

Publication |

Year |

Theme |

Topic |

Orientation |

Type of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stuckelberger & Koedam |

2022 |

P |

How do parties use PMT? |

Interpretative, negative |

Empirical, quantitative |

|

Haenschen |

2022 |

M |

PMT effects on voters |

Descriptive |

Empirical, quantitative |

|

Dobber & Vreese |

2022 |

p |

How do politicians campaign digitally? |

Interpretative, negative |

Empirical, quantitative |

|

Schawel et al. |

2021 |

CC |

User behaviour, PMT |

Descriptive |

Theoretical |

|

Lopez Ortega |

2021 |

M |

Politicians’ use of PMT |

Descriptive |

Empirical, quantitative |

|

Dobber et al. |

2021 |

M |

Effects of PMT |

Descriptive/interpretative, negative |

Empirical, experiment |

|

Lavigne |

2021 |

M |

The (voting) effects of PMT on parties |

Descriptive/interpretative, negative |

Empirical, quantitative |

|

Rhum |

2021 |

P |

Legal view on regulating PMT |

Interpretative, negative |

Theory |

|

Kruikemeier et al. |

2021 |

CC |

Algorithms and a new communication form |

Descriptive |

Essay |

|

Medina Serrano et al. |

2020 |

P |

Politicians’ use of PMT, Germany |

Descriptive |

Empirical, quantitative |

|

Harker |

2020 |

P |

Digital campaigning |

Descriptive/interpretative, negative |

Theoretical |

|

Zarouali et al. |

2020 |

M |

Effects of PMT |

Interpretative, negative |

Empirical, small n study |

|

Haenschen & Jennings |

2020 |

CC |

Mobilisation through digital campaigning |

Interpretative, negative/descriptive |

Empirical, quantitative, field experiment |

|

Burge et al. |

2020 |

CC |

PMT effects on voters |

Descriptive |

Empirical, quantitative |

|

Baldwin-Philippi |

2020 |

CC |

Journalists and data campaigning |

Descriptive |

Empirical, qualitative, discourse analysis |

|

Guerrero-Sole et al. |

2020 |

P |

SoMe, context collapse and the future of data-driven populism |

Descriptive |

Theoretical |

|

Bayer* |

2020 |

P |

PMT violation of citizens, law |

Interpretative, negative |

Essay |

|

Hu |

2020 |

P |

CA scandal, regulation |

Interpretative, negative |

Essay |

|

Kusche |

2020 |

P |

PMT efficiency |

Interpretative, negative |

Theory |

|

Chester & Montgomery* |

2019 |

P |

Privacy, digital strategies, digital transformation |

Interpretative, negative |

Essay |

|

Burkell & Regan* |

2019 |

P |

PMT critic |

Interpretative, negative |

Essay |

|

Krotzek |

2019 |

M |

Efficiency |

Descriptive |

Empirical, small n experiment |

|

Susser et al.* |

2019 |

CC |

PMT and manipulation |

Interpretative, negative |

Essay |

|

Hegazy* |

2019 |

M |

Neuromarketing, efficiency |

Interpretative, negative |

Review, illustrative case study, qualitative |

|

Baldwin-Phillippi* |

2019 |

CC |

Review, efficiency |

Descriptive |

Review |

|

Haenschen & Jennings* |

2019 |

CC |

Efficiency: Voter persuasion |

Descriptive |

Empirical, field experiment |

|

Dobber et al.* |

2019 |

P |

Europe, GDPR, law |

Descriptive/interpretative, negative |

Essay |

|

Nenadic* |

2019 |

P |

Europe, GDPR, disinformation Law |

Interpretative, negative |

Essay |

|

Dommett & Power* |

2019 |

P |

PMT, UK experiences |

Descriptive/interpretative, negative |

Empirical, quantitative, secondary data |

|

Aagaard* |

2019 |

CC |

Review, campaign strategy |

Descriptive/interpretative, negative |

Empirical, qualitative, case study |

|

Dommett* |

2019 |

CC |

Theory, UK experiences |

Descriptive |

Empirical, qualitative, case study |

|

Endres & Kelly |

2018 |

CC |

Efficiency of PMT |

Descriptive |

Empirical, quantitative, survey |

|

Ward |

2018 |

P |

Ethics, Cambridge Analytica |

Interpretative, negative |

Empirical, qualitative, case study |

|

Zuiderveen Borgesius et al. |

2018 |

P |

Law, privacy, campaign strategy |

Descriptive, interpretative (negative & positive) |

Essay |

|

Papakyriakopoulos et al. |

2018 |

P |

German experiences |

Descriptive, interpretative, negative |

Empirical, quantitative, big data set |

|

Trish |

2018 |

P |

Political economy and PMT |

Interpretative, negative |

Empirical, qualitative, cases |

|

Owen* |

2018 |

CC |

Hybridity |

Descriptive/interpretative, negative |

Theory |

|

Kruschinski & Haller |

2017 |

P |

German experiences |

Descriptive |

Empirical, qualitative |

|

Patten |

2017 |

P |

PMT, permanent campaign, Canadian experiences |

Descriptive/interpretative, negative |

Empirical, case study |

|

Anstead* |

2017 |

P |

Campaign strategy, UK |

Descriptive/interpretative, negative |

Qualitative, case study |

|

Bodo et al.* |

2017 |

P |

Law, comparative |

Descriptive |

Essay |

|

Chester & Montgomery* |

2017 |

P |

PMT tools |

Interpretative, negative |

Essay |

|

Dobber et al. |

2017 |

P |

PMT tools, Dutch experiences |

Descriptive |

Qualitative, case study |

|

Cacciotto* |

2017 |

CC |

Efficiency, political consulting |

Descriptive |

Essay |

|

Solovey |

2017 |

CC |

Campaign strategy, efficiency |

Descriptive |

Empirical, qualitative |

|

Gorton* |

2016 |

P |

PMT efficiency, manipulation |

Interpretative, negative |

Essay |

|

Endres |

2016 |

M |

Efficiency |

Descriptive |

Empirical, quantitative, survey-data |

|

Panagopoulos |

2016 |

CC |

Campaign strategy |

Descriptive |

Empirical, secondary survey data, quantitative |

|

Cacciatore et al. |

2016 |

CC |

Campaign strategy, efficiency |

Descriptive |

Theory |

|

Lilleker* |

2016 |

CC |

Campaign strategy, comparative |

Descriptive/interpretation, negative |

Empirical qualitative, content analysis |

|

Jungherr* |

2016 |

P |

Focus on German political culture, comparative |

Descriptive |

Empirical, qualitative, Case study |

|

Jungherr et al.* |

2016 |

M |

SoMe/hybridity |

Descriptive |

Empirical, quantitative |

|

Bennett* |

2016 |

P |

Comparative, law |

Descriptive/interpretation, negative |

Essay |

|

Holtzhausen* |

2016 |

CC |

Digital transformation of politics |

Interpretative, negative |

Theory |

|

Bennett* |

2015 |

P |

Digital transformation of politics |

Interpretative, negative |

Theory |

|

Vergeer* |

2015 |

CC |

SoMe/hybridity |

Descriptive |

Review |

|

Bimber* |

2014 |

CC |

Digital transformation of politics |

Descriptive |

Essay |

|

Rubinstein |

2014 |

P |

Law, privacy |

Interpretative, negative |

Essay |

|

Nickerson & Rogers* |

2014 |

M |

Efficiency, digital transformation of campaign |

Descriptive |

Essay, secondary data illustrations |

|

Nielsen* |

2011 |

P |

Digital transformation of communication context |

Interpretative, positive |

Empirical, qualitative case study |

|

Murray & Scime |

2010 |

M |

Efficiency of PMT |

Interpretative, positive |

Empirical, quantitative |

|

Ridout |

2009 |

CC |

Hybridity, digital transformation |

Descriptive |

Empirical, quantitative |

*Publications not part of Web of Science sample

CC: Communication context; P: Political context; M: Political PMT technique.

Add new comment