The exploitation of vulnerability through personalised marketing communication: are consumers protected?

Abstract

While data-driven personalisation strategies in marketing offer consumers several benefits, they potentially also create new disparities and vulnerabilities in society, and in individuals. This article explores in what ways application of so-called personalised marketing communication may lead to exploitation of vulnerability of consumers and builds on empirical findings on the issue by investigating if consumers are protected against such vulnerabilities under EU consumer protection law. We show a number of ways in which personalisation may lead to exploitation of internal and external vulnerabilities and that EU consumer law contains significant barriers to effectively address such exploitation.Introduction

By undertaking various activities online, consumers are producing a large amount of personal information that is collected and processed by companies (Acquisti et al., 2015). This information is subsequently used to tailor online services by offering personalised communication based on individuals’ characteristics, interests and behaviours (Bol, Dienlin, et al., 2018). While personalisation is currently applied in many different contexts, it very frequently occurs in the form of personalised marketing messages (so-called personalised marketing communication (“PMC”), see Strycharz et al. (2019)).

PMC encompasses different communication techniques that all involve interactions between companies and consumers, data collection and processing by companies and delivering marketing communication (Vesanen & Raulas, 2006). PMC is generally used as an umbrella term for communication about so-called sales and promotion (personalised offers, recommendations and advertising) as well as information provision (Strycharz et al., 2019). It offers consumers a number of benefits, such as increased relevance, informativeness and credibility of communication (e.g., Boerman et al. 2017; Tran 2017). At the same time, by targeting personal characteristics, such tactics make individuals more susceptible to persuasion, blurring the line between persuasion and manipulation. This can be seen as a threat to individual autonomy as well as bringing on a risk of economic harm (Calo, 2014). In doing so, personalisation can thus potentially create new disparities and vulnerabilities in society, and in users (Bol, Helberger, et al., 2018). While the relation between personalisation and consumer vulnerabilities has been receiving growing attention in empirical studies, research on how European consumer law protects against such practices has been scarce. Therefore, the current study builds on the empirical findings by adding a legal perspective on consumer vulnerabilities and PMC.

In order to investigate to what extent EU consumer protection law protects consumers against vulnerabilities arising from PMC, the current research first explores the relation between PMC and vulnerabilities and, next, investigates the protection consumers are offered in this context. The following two research questions will be investigated:

- In what ways can PMC exploit consumer vulnerabilities?

- To what extent are consumers protected against such exploitation under EU consumer protection law?

To answer the first question, we review consumer research on PMC, provide an overview of different types of vulnerabilities described in consumer research and explore in what ways PMC applications may exploit different types of consumer vulnerabilities. The second research question is answered through an analysis of EU consumer law, discussing the relevant pieces of legislation, case law and guidance documents.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. First, the phenomenon of PMC is defined, and the possible exploitation of different types of consumer vulnerabilities explored (Section 1). After that, focus shifts to how PMC is regulated by EU consumer protection law and whether EU consumer law tackles the identified potential for vulnerability exploitation (Section 2). It is shown that EU consumer law contains significant barriers to effectively tackle PMC-related vulnerabilities. This article finishes by a discussion of the implications of this conclusion, in which suggestions are provided on further research and on how EU consumer law could more adequately tackle PMC-related vulnerabilities (Section 3).

Section 1: Personalised marketing communication and consumer vulnerabilities

1.1 Personalised marketing communication – state of the art

Personalisation can be defined as “the strategic creation, modification, and adaptation of content and distribution to optimize the fit with personal characteristics, interests, preferences, communication styles, and behaviours” (Bol, Dienlin, et al., 2018, p. 373). Marketing communication is one of the most common contexts of personalisation online. PMC describes numerous applications that all involve collection and processing of consumer data by organisations (Vesanen & Raulas, 2006).

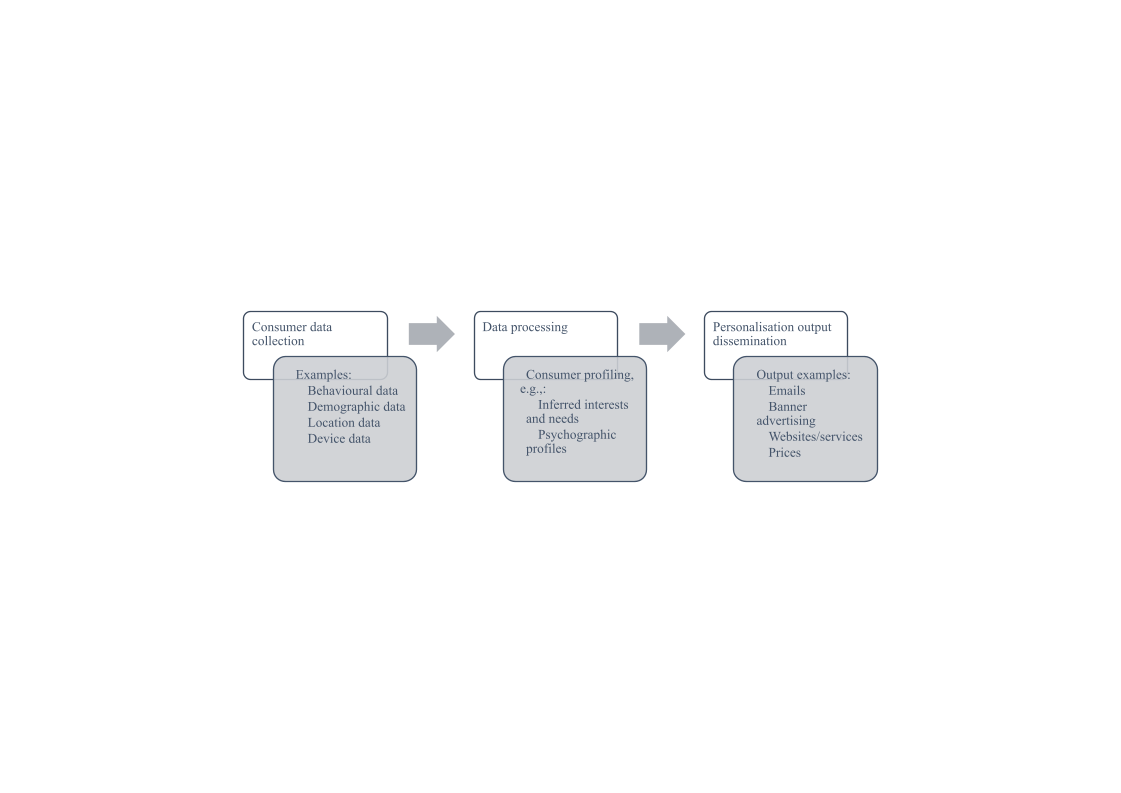

In the personalisation process, first, consumer data is collected with the aim of personalising communication. At this stage, different types of data can be collected. Next, the data are processed with the aim of constructing consumer profiles and inferring information about their needs and interests. In the third step, this information is used to produce personalised communication, which can be distributed through different channels (Strycharz, 2019). Figure 1 provides an overview of this process and includes examples of activities executed at every step. In the following, we apply this differentiation to introduce the PMC applications most used by marketers and investigated in research. Later, these methods will form the starting point for our legal assessment of specific PMC applications.

One of the most common applications of PMC is online behavioural targeting, which can be defined as “adjusting advertisements to previous online surfing behaviour” (Smit et al., 2014, p. 15). This application uses behavioural data of consumers (often combined with other information, such as demographics), which are processed to infer which topics or products are likely to be interesting for an individual and to subsequently select advertising to display (McDonald & Cranor, 2010). A common example for this type of personalisation is showing advertising for products that a user has viewed before online, so-called remarketing, which is widely applied in banner ads on websites, on social media and in follow-up emails sent by online shops.

While behavioural and demographic data are widely used in personalisation, recent developments include personalisation adjusted not only to individuals’ past behaviour and demographics, but also to their unique psychological characteristics, so-called psychological targeting (Matz et al., 2017). Research in psychology indeed shows that psychological characteristics can be accurately inferred from digital footprints, such as likes or posts on social media (Kosinski et al., 2013; Segalin et al., 2017) and that adjusting communication to these characteristics leads to higher persuasiveness of messages. Hirsh and colleagues (2012) were first to show that personalising persuasive messages to personality traits increases their effectiveness. For example, personalised messages matched to people’s extraversion or openness-to-experience resulted in more clicks and more purchases than their unpersonalised counterparts (Matz et al., 2017), while personalised political ads matched to one’s personality traits (predicted based on a text written by the individual) were found to be more persuasive than ads not matching one’s personality (Zarouali et al., 2020). At the same time, this technique is seen as highly controversial due to societal risks involved. The Facebook/Cambridge Analytica scandal in which a political consulting firm built personality profiles of hundreds of millions of Facebook users without their awareness (Dance, 2018) and used them for persuasion purposes, highlighted some of these risks. Regardless of questionable accuracy of personality trait predictions (Marengo & Montag, 2020), psychological targeting is increasingly applied in the industry, often under the name personality-based targeting or psychographic segmentation in which consumers of a company are assigned to different personality segments (Graves & Matz, 2018).

Zooming in to specifically the output of the personalisation process, banners (Boerman et al., 2017) and emails (Maslowska et al., 2011) are commonly used to deliver PMC. In addition, PMC is also applied on own websites and within services of companies. On-site personalisation includes adjusting websites’ look and feel to individual visitors (Hauser et al., 2014). Finally, price differentiation forms a distinct category of personalised output. It can be described as “differentiating the online price for identical products or services partly based on information a company has about a potential customer” (Zuiderveen Borgesius & Poort, 2017, p. 2). Empirical research on price differentiation is scarce (e.g., Fassnacht & Unterhuber, 2016; Wolk & Ebling, 2010), but a recent survey study suggests that consumers regard price differentiation practices as unfair (Poort & Zuiderveen Borgesius, 2019).

For all the PMC applications presented above, so-called A/B testing is crucial for evaluating effectiveness. In such a test, two or more versions of, for example, a website or newsletter are shown to different segments of consumers to determine which version is most effective. In relation to PMC, A/B testing is used to evaluate general optimisation of personalisation systems, for example to test the effectiveness of changes in personalisation algorithms’ parameters (e.g., data or profiling used) or the degree of personalisation (Esteller-Cucala et al., 2019). This allows companies to find the most persuasive techniques for each consumer at a large scale without awareness of the effects of individual changes to the algorithm. Machine learning algorithms are often applied to automate A/B testing. Such algorithms also allow for predicting positive outcomes for individual consumers and thus determining which version one gets to see. Users who are part of such testing are usually not aware that they receive an adjusted form of communication.

While the different PMC applications offer benefits to consumers, they are also a source of worry. Much academic research on negative consequences of PMC has focused on privacy risks (e.g., Schumann et al., 2014; McDonald & Cranor, 2010) showing that, for example, consumers worry that personal information could be misused or sold to third parties (Dinev & Hart, 2006). However, a survey among Dutch consumers has shown that they also fear being manipulated and excluded from offers and information (Strycharz et al., 2019). They feel that their personal or psychological characteristics may be (mis)used by companies. The following section therefore links PMC to a definition of consumer vulnerability to present how certain applications of personalisation can lead to vulnerability exploitation.

1.2 Personalised marketing communication and consumer vulnerabilities

In consumer research, the term vulnerability has a broad range of applications, such as individual characteristics (e.g. age), social phenomena (e.g. stereotyping), business practices (e.g. marketer manipulations), and environmental forces (e.g. natural disasters). It has been emphasised that the term should not be used simply to describe certain designated consumers (such as children), as belonging to such a group does not necessarily make individuals vulnerable: “It is the circumstances that consumers face that determine their vulnerability” (Hill & Sharma, 2020, p. 4). All people may experience vulnerability in some situations. Therefore, defining vulnerability based on group membership is limiting as vulnerability can also be individual and contextual, i.e., stemming from the situation one is in (e.g., external circumstances that lead to distress) (Baker et al., 2005). Consumers vary in the extent to which they are vulnerable in different contexts, across time and place (Hill & Sharma, 2020). This is particularly relevant in the context of this study as PMC does not necessarily involve exploiting vulnerabilities of certain groups (e.g., targeting young consumers). Rather, some PMC applications can be used to render individuals vulnerable in a certain context by using information on them for persuasive purposes (e.g., using information on one’s psychographic profile in online interactions).

Regarding different sources of vulnerabilities, Baker and colleagues (2005) proposed a distinction between vulnerability stemming from internal or external factors. On the one hand, internal factors are related to individual characteristics (e.g., skills or literacy) and individual states (e.g., motivation or stress). On the other hand, external factors include a lack of access to goods and services (e.g., having limited access to the internet impeding one’s possibility to use a webshop) and the environment one operates in (e.g., the design of a website or physical place). In the remainder of this section, we will present examples how applying PMC can lead to exploitation of internal and external vulnerabilities.

Regarding internal factors, lack of understanding of targeting can make consumers vulnerable. Vulnerability may occur due to a diminished capacity to understand advertising, products, or both (Smith & Cooper-Martin, 1997). When being exposed to a persuasion attempt, e.g., a personalised ad, individuals employ three different knowledge structures to decide how to cope with this situation, namely 1) topic knowledge, i.e., beliefs about the subject of the persuasive message; 2) agent knowledge, i.e., beliefs about the party responsible for the message; and 3) persuasion knowledge, i.e., beliefs about the persuasive tactic used, the context in which it was used and its effectiveness (see the Persuasion Knowledge Model by Friestad & Wright, 1994). If consumers lack one of these knowledge structures, it diminishes their coping mechanisms and makes them vulnerable to manipulation. In the context of PMC, Smit and colleagues (2014) have shown that consumers have insufficient knowledge to understand its working as the majority of consumers does not understand how their data is collected or what obligations companies have when they collect and process their data.

Another way in which PMC may lead to exploitation of internal vulnerabilities is psychological targeting, as it gives companies an opportunity to target internal factors to make users more vulnerable to persuasion in a specific context. Past research has discussed it as a threat to consumer autonomy and privacy as this practice negatively affects one’s ability to make a rational decision (Ward, 2018). Receiving messages personalised in a way that specifically targets the personality of individuals hinders their ability to accurately sense when and how they are being manipulated. The sender can identify and target specific consumers that are more likely to react to a particularly framed message based on their personality traits, while bypassing others for whom this message could have an undesired effect (Tufekci, 2014). For example, impulsiveness can be triggered by targeting personality traits. Such traits can be predicted from one’s language use on social media and past research has shown that certain personality traits strongly correlate with one’s impulsiveness (Park et al., 2015). Such targeting of personality traits leading to human irrationality shows that psychological targeting can also be seen as exploitation of individual vulnerable states. This indicates that psychological targeting might take advantage of consumers’ psychological weaknesses, beyond the light of their own awareness (Ward, 2018).

Personalisation can also be used to exploit the fact that vulnerability can be contextual. As Calo (2014) argues, collecting consumer data and processing it to construct individual profiles “permits firms to surface the specific ways each individual consumer deviates from rational decision-making, however idiosyncratic, and leverage that bias to the firm's advantage” (p. 1003). When applying PMC, organisations can explicitly personalise messages based on the inferred psychological state and the specific life situation of consumers. In the past, Facebook allegedly offered advertisers the option to target young users in a state of psychological vulnerability, inferring when the users feel insecure and stressed (Tiku, 2017). In a similar pattern, a marketing firm found that women feel less attractive on Mondays, especially in the morning, and recommended targeting women with beauty products specifically at that time of the week (PHD Media, 2013).

Next to internal factors, external factors that render consumers vulnerable can also be used to make personalisation more effective. Although there is lack of empirical research on the impact of external factors, numerous examples from the industry show how data on externalities can be used for PMC. One example concerns personalised dynamic pricing techniques, which have recently been criticised for not only being based on current market demand, but also on external factors that render individuals more in need of a service. For example, Uber has been criticised for increasing their price due to severe weather or ongoing safety issues (such as terrorist threats) knowing that in such a situation, consumers are in higher need of their services (Weiner, 2014). The same company has also been criticised for using data on the consumer’s device to identify whether the battery of the mobile device is low, and Uber’s services are urgently needed (Golson, 2016). Use of this type of data on external and situational factors about the consumer explicitly exploits the vulnerable situation they are in.

In conclusion, PMC applications can exploit consumer vulnerabilities in several ways. First, lack of understanding of targeting makes consumers vulnerable. Second, exploiting personality traits of consumers may lead to exploiting individual irrationalities. Third, PMC makes it possible to target consumers who are less rational due to other internal vulnerabilities, such as illness or psychological distress as well as due to external factors. In the next section we will provide an overview to what extent EU consumer law takes the relation between PMC and vulnerabilities into account and offers consumer protection.

Section 2: Personalised marketing communication and EU consumer protection law

2.1 Introduction

In legal literature, personalised marketing communication has so far been discussed mainly from the perspective of data protection (e.g., Zuiderveen Borgesius et al., 2017; Steppe, 2017; Zuiderveen Borgesius & Poort, 2017; Wachter, 2020; Finck, 2021) and, to a lesser extent, non-discrimination law (see e.g., Wachter, 2020; Zuiderveen-Borgesius, 2020; Gerards & Zuiderveen Borgesius, 2021). However, to address the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC, consumer protection laws can be highly relevant as well. This is especially so because data protection law—at least in the EU—leaves significant room for the processing of data for PMC, in particular if consumers have consented to it (Zuiderveen Borgesius et al., 2017; Galli, 2020, also on the notion of “consent” under EU data protection law). In addition, the potential of EU data protection law to address the risks of PMC seems limited, taking into consideration that people tend to consent to the processing of personal data even if they believe that their privacy is important (Acquisti & Grossklags, 2005; Zuiderveen Borgesius et al., 2017; Finck, 2021) and because it is questionable whether people truly understand the contemporary data systems and the consequences of their consent (see Finck, 2021, also for other limitations of EU data protection law in relation to personalised marketing). The remainder of this article therefore addresses to what extent consumers are protected against the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC under EU consumer protection law.

Two pieces of EU consumer protection legislation are of particular relevance to this topic. Firstly, PMC is regulated by the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (2005/29/EC, “UCPD”), which is the primary legislative instrument in EU consumer protection law regulating marketing, including advertising. The UCPD does not provide specific rules on PMC, but it does regulate PMC through its clauses that apply to commercial practices in general. For example, PMC can be prohibited under circumstances if it contains misleading information or if it unduly puts the consumer under pressure. Secondly, the Consumer Rights Directive (2011/83/EU, “CRD”) will—as of 28 May 2022—regulate a specific form of PMC: personalised pricing. Below it is discussed to what extent these two legislative instruments protect consumers against the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC.

2.2 PMC and the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive

The Unfair Commercial Practices Directive

The UCPD harmonises the regulation of business-to-consumer commercial practices in the EU. By doing so, the UCPD aims to increase the smooth functioning of the internal market while at the same time achieving a high level of consumer protection (Article 1 UCPD). The scope of the UCPD is particularly broad, as it covers any business-to-consumer commercial practice. As confirmed by the European Court of Justice (“CJEU”), this essentially includes any type of business-to-consumer advertising and marketing, including one-to-one commercial practices (CJEU C-388/13 UPC). This is relevant in the context of PMC: even communications that are fully personalised (i.e., personalised at the level of one single consumer) are “commercial practices” as defined by the UCPD.

The UCPD contains a mix of general and specific prohibitions of unfair commercial practices. In particular, it contains a general prohibition of unfair commercial practices as well as general prohibitions of misleading and aggressive commercial practices. Apart from these general prohibitions, the UCPD also contains a “black list” of specifically defined commercial practices that are deemed unfair under all circumstances.

The European Commission published a guidance document on the application of the UCPD, which was last updated in 2016 (“EC Guidance”; European Commission, 2016). The EC Guidance is not binding upon EU and national institutions, but it does provide insight into how the UCPD should be interpreted according to the European Commission. Similarly, national enforcement authorities have published guidance documents on the application of the UCPD, sometimes including specific guidelines in relation to PMC.

The UCPD was recently amended by the so-called Modernisation Directive (2019/2161/EU), which aimed to bring several EU consumer law directives up to date with technological and societal developments, including the shift from offline to online marketing and purchasing in recent years (Twigg-Flesner, 2018; Loos, 2019; Duivenvoorde, 2019). However, no amendments were introduced to the UCPD that specifically addressed PMC.

Benchmarks for protection under the UCPD

In the application of the general prohibitions in the UCPD (such as the prohibitions of misleading and aggressive commercial practices), the national courts and enforcement authorities must assess whether the economic behaviour of the “average consumer” is distorted by the practice at hand (see e.g., Article 5.2(b) UCPD). This average consumer is deemed to be “reasonably informed, observant and circumspect” (Recital 18 UCPD; CJEU C-210/96 Gut Springenheide). In practice, this means that the average consumer is generally expected to understand that advertising should be taken with a pinch of salt. It also means that the average consumer is in principle expected to read all information supplied to him and to make a rational choice based on this information. This has raised significant criticism in literature, taking into consideration that—as evidenced by behavioural insights—consumers often do not consider all information available and do not take rational decisions due to biases in their decision making (Franck & Purnhagen, 2014; Duivenvoorde, 2015; Van Boom, 2016). If the economic behaviour of the average consumer is not distorted, e.g., because the average consumer is expected to understand the persuasive tactics used and to respond rationally, the practice is—in principle—not prohibited.

Since the average consumer benchmark is the default benchmark in the UCPD, the UCPD in principle disregards vulnerabilities of consumers who, either globally or in a specific context, do not meet the standard of the average consumer. This presents a significant barrier for courts and enforcement authorities to tackle the exploitation of vulnerabilities, including through PMC applications (see similarly for US law, which operates the standard of a “reasonable person”: Willis, 2020). In particular, the average consumer benchmark disregards that all people may experience vulnerability in some situations. This is problematic from the point of view of tackling the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC, especially because companies may use PMC to exploit consumer vulnerabilities at the individual level, e.g., through psychological targeting or by targeting consumers that are—for whatever reason, and in the situation at hand—identified as being less rational.

However, benchmarks other than the “average consumer” can be applied under certain circumstances. Through the application of these alternative benchmarks, courts and enforcement authorities can—at least to some extent—take into account the behaviour of specific groups of consumers. This can lead to a higher level of consumer protection in specific cases (Duivenvoorde, 2013).

The first of these alternatives is the target group benchmark. If a commercial practice is directed at a specific group of consumers, the average member of that group is taken as the benchmark (Article 5.2(b) UCPD). For example, for a TV commercial that is broadcasted right before a children’s TV show, the average child watching the show serves as the benchmark in assessing the fairness of the commercial practice. The target group benchmark can to some extent help to address PMC-related consumer vulnerability. If PMC is targeted at a specific group, the average member of that specific group can serve as the benchmark. For example, if an online advertisement is specifically directed to a group of consumers who are likely to react to that advertisement less rationally due to a personality trait (psychographic segmentation), the behaviour of the average member of that group can be taken into account—rather than the rather rational behaviour of the “average consumer”.

However, in practice it will most likely be difficult for the authorities to ascertain that a specific PMC practice is actually targeted at a specific group, and that this group is indeed less rational or attentive. This applies in particular to marketing communication that is personalised at the individual level, e.g., on the basis of automated individualised A/B testing, see Section 1.1. This will make it difficult (if not: impossible) to determine that a “group” is targeted. In such a case, it will not only be difficult to determine for an enforcement authority what “group” is targeted, but also how the average member of this group is expected to respond (see similarly in relation to US law: Willis, 2020).

Arguably, if PMC is personalised at the level of an individual consumer, the individual consumer could serve as the “target group”. This view is in fact taken by the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets in its guidance on the protection of the online consumer (Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets, 2020, pp. 15 and 26). It is questionable whether this view is indeed in line with the UCPD, in particular because according to the wording of the UCPD an actual “group” must be targeted in order for the target group benchmark to be applicable. Hence, it is doubtful whether the target group benchmark can actually serve to protect consumers when PMC is truly personalised.

The second alternative to the average consumer benchmark is the vulnerable group benchmark (Article 5.3 UCPD). If a commercial practice affects a particularly vulnerable group, the average member of that group serves as the benchmark. Rather than focusing on who is targeted by the commercial practice, this benchmark focuses on who is affected by the practice. Hence, the added value of the vulnerable group benchmark compared to the target group benchmark is that this benchmark can also be applied if a company is not targeting its marketing communication to a specific group (Anagnostaras, 2010; Trzaskowski, 2016). Article 5.3 UCPD specifically refers to vulnerability due to “age, mental or physical infirmity or credulity”, but also seems to be applicable to other potential sources of group-based vulnerability (Anagnostaras, 2010; Duivenvoorde, 2013; Trzaskowski, 2013).

However, the vulnerable group benchmark is only applicable if certain requirements are fulfilled. Firstly, Article 5.3 UCPD essentially only takes into account group-based vulnerabilities and not individual and contextual vulnerabilities. Hence, the notion of vulnerability in the UCPD is considerably narrower compared to the understanding of vulnerability in consumer research. Secondly, the vulnerability must be reasonably foreseeable to the company. And finally, the vulnerable group must be “clearly identifiable”. These requirements tend to significantly limit this benchmark’s scope of protection (Duivenvoorde, 2013; Trzaskowski, 2013; Galli, 2020; Helberger et al., 2021, p. 25). At the same time, it could be argued that the requirement of reasonable foreseeability could be fulfilled more easily in a PMC context, at least if the vulnerability of a particular group is apparent to the company due to the data that is available to it. Still, it will likely be difficult in practice for the authorities to pinpoint a specifically vulnerable group that is clearly identifiable and to prove that the vulnerability of this group was indeed reasonably foreseeable to the company. This is especially the case because companies may base their targeting on a combination of different characteristics (such as multiple demographics as well as past online behaviour), rather than on a one specific group characteristic.

All in all, the potential of the vulnerable group benchmark to address consumer vulnerability in the context of PMC seems limited and is therefore ill-fitted to effectively deal with the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC. This is especially the case because the approach of addressing group-based vulnerability disregards that vulnerability, as is pointed out by Baker and colleagues (2005), can be temporary and related to external factors.

PMC and misleading commercial practices

The UCPD prohibits misleading commercial practices. In particular, it prohibits misleading actions (i.e., misleading consumers by providing them with false or misleading information, Article 6 UCPD) and misleading omissions (i.e., withholding essential information to consumers, Article 7 UCPD). For any PMC practice to be assessed as misleading, it must either be misleading to the average consumer (or possibly to the target group or vulnerable group, if such a benchmark is applicable) or must omit essential information (such as the full price inclusive of taxes and additional costs). Hence, the starting point is that influencing consumers is in principle allowed, as long as consumers are provided with sufficient and correct information. This is in fact one of the guiding principles in EU consumer protection law, which is also known as the “information paradigm” (Reich & Micklitz, 2014, p. 22; Van Boom, 2016, p. 402).

In principle, the UCPD does not require companies to disclose that marketing communication is personalised (see for the discussion whether and to what extent a similar duty exists under EU data protection law e.g., Veale & Edwards, 2019; Galli, 2020; Malgieri, 2019). This is another barrier in effectively tackling the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC, taking into consideration that lacking such knowledge makes it more difficult for consumers to cope with vulnerabilities arising from PMC.

Arguably, not disclosing to consumers that an offer (such as a price for a specific product) is personalised does qualify as a misleading omission under Article 7 UCPD. This view has both been taken by the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets and—before Brexit—the UK Office of Fair Trading (Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets, 2020, pp. 26-27; Office of Fair Trading, 2013, p. 32). The EC Guidance does not go as far. In the EC Guidance, it is merely stated that “[a]s with dynamic pricing and price discrimination, under the UCPD traders are free to determine their prices if they duly inform consumers about the prices or how they are calculated” (European Commission, 2016, p. 134). This seems to indicate that companies can personalise prices and are merely held to be transparent to the consumer what the price of a specific product is, rather than having to explain that this price has been personalised. As will be shown below, such a duty does arise from the amended Consumer Rights Directive.

PMC and aggressive commercial practices

The UCPD also prohibits aggressive commercial practices (Articles 8 and 9 UCPD). In essence, aggressive commercial practices are selling techniques which limit the consumer’s freedom of choice or conduct regarding the product by use of harassment, coercion (including the use of physical force) or undue influence. These are practices that are thought to distort the free shaping of the will of the consumer, using techniques which compromise the consumer’s freedom of choice (Carballo-Calero, 2016).

The prohibitions of aggressive practices in the UCPD (including the “black list” of aggressive practices) do not specifically regulate PMC. In order for a practice to be prohibited, (i) a company must exercise harassment, coercion or undue influence and (ii) this practice must impair the average consumer’s freedom of choice (or, under circumstances: that of an average member of the target group or the vulnerable group) in a way that causes him or is likely to cause him to take a transactional decision that he would not have taken otherwise. From these requirements it follows once more that influencing consumers (either through regular advertising or through PMC) is in principle allowed (see also European Commission, 2016, p. 78), with the exception that the company may not exercise harassment, coercion or undue influence—notions that seem to point to rather clear-cut cases of unduly pressuring consumers to do something against their will. In addition, the average consumer benchmark again serves as a significant barrier in effectively protecting consumers against the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC.

Still, PMC practices could be prohibited as aggressive commercial practices under specific circumstances. Especially “undue influence” can be of relevance to PMC. Undue influence is defined in Article 2(j) UCPD as “exploiting a position of power in relation to the consumer so as to apply pressure, even without using or threatening to use physical force, in a way which significantly limits the consumer’s ability to make an informed decision.” The UCPD does not make clear when a “position of power” exists, but the UCPD seems to refer to a specific position of power of the company vis-à-vis the consumer, rather than structural market inequalities (such as information asymmetry) (Caronna, 2018). Such a position of power could exist, for example, if the consumer has become psychologically dependent on the company (Micklitz et al., 2010, pp. 147-148). Arguably, the context of PMC (in which companies collect data on consumers’ behaviour in order to influence them more effectively) can put those companies into a position of power (see also Helberger et al., 2021). This could be the case in particular if the company holds information on vulnerability of the consumer, such as the psychological state of the consumer (e.g., state of distress) or on detrimental external circumstances (such as the consumer having to book a taxi while having a low phone battery).

However, the mere imbalance of power is insufficient to conclude that the company is exercising undue influence (see the text of Article 2(j) UCPD cited above and Caronna, 2018). A practice constitutes undue influence only if the company is exploiting the power imbalance and is applying pressure onto the consumer, in a way that makes the consumer uncomfortable and confuses their thinking in relation to the decision they are about to take (CJEU C-628/17 Orange Polska). In the words of Advocate-General Campos Sánchez-Bordona, this pressure must cause “the forced conditioning of the consumer’s will” (Opinion in cases C‑54/17 and C‑55/17 AGCM v Wind and Vodafone). For example, charging a higher price to consumers who are in a hurry to book a taxi ride is in itself not putting the consumer under pressure. This could possibly be different if the taxi company would send a pop-up message to the consumer saying that “Your battery is low – book this ride immediately!”.

In this context, it is important to note that Article 9 UCPD emphasises that one of the elements that should be taken into account when assessing whether a practice constitutes undue influence is “the exploitation by the trader of any specific misfortune or circumstance of such gravity as to impair the consumer’s judgement, of which the trader is aware, to influence the consumer’s decision with regard to the product”. Also on the basis of this provision it seems likely that merely contracting with a consumer who is in high need of a product or service, or even charging a higher price to such a consumer, is insufficient for the practice to be aggressive. Again, it seems that additional circumstances are needed. Similarly, the mere targeting of advertising to consumers who are in a vulnerable psychological state is unlikely to constitute an aggressive commercial practice in itself. For example, targeting online advertising for a book on “better sleeping” to people who are awake in the middle of the night and are therefore likely to have sleeping problems is probably not aggressive as such, but repeated targeting of such advertising during the night could well be (since this could constitute putting the consumer under pressure).

In conclusion, the prohibition of aggressive commercial practices does provide some potential to tackle the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC, but only under specific circumstances. The notions of harassment, coercion and undue influence are essentially written to challenge rather clear-cut practices, which involve unduly pressuring consumers to do something they do not intend to. In contrast, the exploitation of PMC will often involve more subtle ways of influencing consumers, such as psychological targeting or personalising content on the basis of the inferred psychological state or life situation of a consumer. Such forms of PMC can exploit consumer vulnerabilities, without clearly satisfying the requirements of Articles 8 and 9 UCPD.

PMC and the general clause

Commercial practices are also prohibited if they are “contrary to the requirements of professional diligence”. This follows from the general prohibition of unfair commercial practices in Article 5 UCPD. The general clause essentially functions as a “safety net” in the UCPD: if a practice is neither misleading nor aggressive, the practice may still be prohibited as unfair under Article 5. So far, courts and enforcement authorities have only sparsely applied this clause (see European Commission, 2016, p. 51 for examples), simply because cases are dealt with through the more specific prohibitions of misleading and aggressive commercial practices.

However, this general prohibition can be of use in relation to practices that were not foreseen at the time the UCPD was introduced, including PMC. In order for PMC practices to be prohibited under Article 5 UCPD, the practice at hand must—in essence—go against the normative values that apply in the specific field of business activity (European Commission 2016, p. 51). This provides some potential to challenge the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC, but only if the practice is not accepted within the industry. For example, targeting impulsive consumers with advertising for products that they are likely to regret purchasing could potentially qualify as an unfair commercial practice, provided that it can be established that such a group has been specifically targeted. If this cannot be established, the practice is likely to be allowed, taking into consideration that the average consumer is in principle expected to respond rationally. Similarly, targeting teenagers who feel insecure and stressed with advertising which makes use of their mental states, could qualify as an unfair commercial practice (also it does not involve putting the teenagers under pressure), again provided that such a group has been targeted specifically. However, it must be noted that this is unchartered territory, and that the notion of professional diligence is notoriously vague.

2.3 PMC and the Consumer Rights Directive: price personalisation

The Consumer Rights Directive (2011/83/EU, “CRD”) deals with several aspects of consumer contracts, including the conclusion of distance contracts (such as online purchases). Like the UCPD, the CRD has recently been amended by the Modernisation Directive (2019/2161/EU). The Directive introduces a new information duty to the CRD for companies that apply price personalisation in the context of distance contracts (including online sales). This new rule will have to be implemented by the EU member states ultimately by 28 November 2021 and applied as of 28 May 2022.

The Modernisation Directive emphasises that companies are allowed to personalise prices for specific consumers or specific categories of consumers based on automated decision-making and profiling of consumer behaviour. However, companies will have to inform consumers if they do so (see Recital 45 of the Preamble to the Modernisation Directive and Article 4.4(a)(ii) Modernisation Directive). The information duty does not apply to techniques such as ‘dynamic’ or ‘real-time’ pricing that involve price changes in response to market demands (Recital 45 of the Preamble to the Modernisation Directive). Hence, this information duty does not apply to a taxi company that raises prices in bad weather conditions or ongoing safety issues.

Companies must supply the information on price personalisation to the consumer in a clear and comprehensible manner, before the contract between the company and consumer is concluded. On the basis of the wording of the new provision, it will be sufficient if the company informs the consumer that a price has been personalised, without disclosing (i) what data the personalisation has been based on and (ii) to what extent the personalised price is different to the price offered to other consumers.

The new information duty does—to some extent—address the lack of understanding of price personalisation that consumers may have and that can make them vulnerable to this practice. The new information duty will at least ensure that consumers will be aware that a price is personalised. At the same time, it is questionable whether consumers will really understand the (in some cases: negative) effects of personalised pricing in a specific case, taking into consideration that companies will not be obliged to disclose what data the personalisation is based on and to what extent this price is different to that of other consumers.

Section 3: Conclusion and implications

3.1 Conclusion

The aim of this article was to examine the ways in which PMC can exploit consumer vulnerabilities as well as to analyse to what extent consumers are protected against such exploitation under EU consumer law. A review of past empirical literature showed that PMC indeed has the potential to exploit both internal and external vulnerabilities. Internal vulnerabilities can be exploited in three ways. First, due to a lack of appropriate persuasion knowledge about PMC, consumers may not be able to adequately respond to the persuasion attempt. Second, psychological targeting renders consumers less rational in reaction to PMC. Finally, utilising the fact that internal vulnerability can also be temporary and contextual, organisations can exploit such vulnerabilities in users by creating an environment that takes advantage of, for example, consumers’ emotional states or personal concerns. Regarding external vulnerability, companies can take advantage of the environment of the consumer and exploit the consumer’s lack of access to resources.

As to the legal protection against the possibilities for exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC, this article has shown that PMC is not specifically regulated under EU consumer law, with the exception of the new information duty on personalised pricing in the CRD. PMC practices can be prohibited under circumstances, just as other (non-personalised) commercial practices. However, the system of consumer benchmarks in the UCPD constitutes a significant barrier in effectively tackling the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC. In addition, even if it can be established that the average consumer or a specific target group or vulnerable group is harmed, PMC applications that exploit consumer vulnerabilities will in most cases not be typical misleading or aggressive practices. Instead, the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC may well involve more subtle ways of influencing consumers, which lend their effectiveness to being based on individual profiles inferred from data collected on the specific consumer (such as the consumer’s tendency to react less rationally in certain situations). Such applications may potentially qualify as unfair commercial practices, but the UCPD is clearly not written to tackle such cases.

3.2 Implications for consumer law and future research

What are the implications of these conclusions? We will discuss how EU consumer law could respond in order to tackle the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC more effectively and address the implications of our conclusions for future research.

Taking into consideration that EU consumer law aims to achieve a high level of consumer protection, it would make sense to strengthen EU consumer law in order to tackle the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC more effectively. The exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC can be seen as harmful both for individuals (as a threat to the autonomy to make informed decisions, see Calo, 2014 and Susser et al., 2019) and for the economy (since consumer manipulation potentially constitutes market failure, see Averitt & Lande, 1997; Hanson & Kysar, 1999; and Calo, 2014). Framed differently: the potential of exploitation of consumer vulnerabilities through PMC is likely to increase the power asymmetry between companies and consumers (Calo, 2014; Helberger et al., 2021). Consumer law could do something about it.

By saying this, we do not imply that EU consumer law is the only field of law through which exploitation of PMC-related vulnerabilities can be tackled. For example, specific risks of discrimination through PMC (such as through price discrimination) could be tackled through non-discrimination law (see e.g., Zuiderveen-Borgesius, 2020; Gerards & Zuiderveen Borgesius, 2021). In addition, the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC could partly be prevented by limiting the possibilities for companies to collect data through data protection law (see Calo, 2014; Zarsky, 2019). However, taking into consideration that consumer law (more than data protection law) aims at protecting consumers against economic harm by reducing power asymmetries between companies and consumers, it makes sense to look at EU consumer law to at least offer part of the solution.

This is not to say that an “easy fix” is available for EU consumer law to effectively tackle vulnerability exploitation through PMC. For example, an overall ban on PMC (as has been defended by some, see Willis, 2020) would be undesirable for many, taking into consideration that PMC can also be beneficial to consumers in many ways (e.g., Boerman et al., 2017; Tran, 2017). Moreover, this article has shown that the relationship between PMC and consumer vulnerability is complex and multi-dimensional. As a result, it seems impossible to solve the problem by simply replacing the notion of vulnerability in the UCPD (Article 5.3) with a new and better one. Rather than trying to implement an easy fix, it makes sense to strengthen EU consumer law through a combination of improvements.

One improvement could be a progressive interpretation of the UCPD by courts and enforcement authorities. For example, the CJEU could recognise that the average consumer does not always respond rationally to commercial practices, in particular if such practices are personalised. This would make it easier for national courts and enforcement authorities to assess the exploitation of PMC-related vulnerabilities as unfair, also if no clear “target group” or “vulnerable group” can be identified (as is the case when, for example, marketing communication is personalised at the individual level).This would increase the potential of the UCPD to tackle the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC, in particular under the general prohibition of unfair commercial practices (Article 5 UCPD) and the prohibition of aggressive commercial practices (Articles 8 and 9 UCPD). The European Commission could help facilitate this process by clarifying in the EC Guidance what is expected of the average consumer in relation to PMC and under what circumstances PMC practices are deemed to be unfair.

In addition, changes to EU consumer law could strengthen its potential to effectively tackle the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC. For example, an information duty could be introduced to ensure that consumers are informed that commercial content is personalised and on the basis of what data this is done. This could increase consumers’ persuasion knowledge and help them to deal with personalised persuasion attempts (see Section 1.2). In fact, such a transparency requirement has recently been proposed as part of the EU Digital Services Act (“DSA”, European Commission, 2020), which is an ambitious attempt to introduce more stringent rules on internet intermediaries in relation to a broad range of issues (Savova, et al., 2021; Savin, 2021; Cauffman & Goanta, 2021). Article 24 of the DSA proposes that in case of personalised advertising, online platforms must provide “meaningful information about the main parameters used to determine the recipient to whom the advertisement is displayed.” However, this information duty is limited to advertising via online platforms and thus does not apply to other forms of PMC, such as personalised apps and webshops. In addition, it is questionable whether the duty to inform consumers about “the main parameters” will actually make consumers understand whether and how their vulnerabilities are being targeted. Moreover, even if a broader information duty would be introduced (e.g., in the UCPD, taking into consideration that the DSA will apply to online intermediaries only), it is important to realise that being unaware of the persuasive tactics applied in marketing content is just one of the ways in which PMC may lead to exploitation of consumer vulnerabilities (see Section 1.2). Finally, consumer research shows that information duties tend to have a limited effect in effectively empowering consumers (see for empirical research on transparency and consumer empowerment in the context of consent for data collection and processing for PMC, Strycharz et al., 2021; see for the difficulties of effectively explaining the negative consequences of PMC in relation to data protection law also, Wachter et al., 2018). Hence, an information duty can only be part of the solution.

An additional measure to more effectively tackle the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC could be to introduce a clause in the UCPD that essentially prohibits PMC applications that are designed to exploit the vulnerabilities of one or more consumers, without the UCPD’s consumer benchmarks being applicable to this clause. Such a clause could be accompanied by the introduction of a number of new practices on the UCPD’s black list, which specifically address PMC practices exploit vulnerabilities.

Finally, in order to effectively enforce the UCPD in relation to PMC, it would make sense to introduce a duty for companies applying PMC to disclose for each marketing message which consumers have been targeted and on the basis of what parameters. This would make it easier for courts and enforcement authorities to determine what the target group is in case of PMC. The DSA (Article 30) proposes such a duty for very large online platforms (i.e., gatekeeper platforms such as Google and Facebook), which will have the obligation to publish a database containing, for each advertisement displayed, what consumers have been targeted and on the basis of which main parameters. Introducing such a duty for all companies that apply PMC could further help tackling the exploitation of vulnerabilities through PMC.

Further legal research could be conducted in order to develop these proposals (and quite possibly: others) in detail. In addition, empirical research on the contextual and external types of vulnerabilities in online interactions with companies is necessary to make identification of vulnerability exploitation easier. While conceptualising these new forms of digital vulnerability has received growing attention (Hill & Sharma, 2020), research on operationalising these vulnerabilities and their role in consumer online interactions is still scarce. In addition, studying vulnerabilities that are temporal and contextual, rather than permanent and group-based, poses new challenges to the field. Traditional empirical methods used to study group-based vulnerabilities are often not applicable in this context. However, as shown by Bol et al., 2020, studies using “digital trace data” have the potential to uncover the relation between personalisation and vulnerability factors. Such data can be collected through tracking consumer behaviour and their exposure to PMC (Bol et al., 2020) or by analysing data voluntarily donated to researchers by individuals (data obtained through access requests under the GDPR, see Boeschoten, 2020). Another possibility for identifying the link between PMC and consumer vulnerabilities is use of ad archives, i.e., publicly accessible databases documenting advertisements on different platforms (Leerssen et al., 2019). Such empirical research into the link between PMC and consumer vulnerabilities on an individual level can also provide further insights into the necessary protection for consumers.

References

Acquisti, A., Brandimarte, L., & Loewenstein, G. (2015). Privacy and human behavior in the age of information. Science, 347(6221), 509–514. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa1465

Acquisti, A., & Grossklags, J. (2005). Privacy and rationality in individual decision making. IEEE Security and Privacy Magazine, 3(1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2005.22

Anagnostaras, G. (2010). The Unfair Commercial Practices Directive in Context: From Legal Disparity to Legal Complexity? Common Market Law Review, 147–171.

Averitt, N. W., & Lande, R. H. (1997). Consumer sovereignty: Unified theory of antitrust and consumer protection law. Antitrust Law Journal, 65(3), 713–756.

Baker, S. M., Gentry, J. W., & Rittenburg, T. L. (2005). Building Understanding of the Domain of Consumer Vulnerability. Journal of Macromarketing, 25(2), 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146705280622

Boerman, S. C., Kruikemeier, S., & Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. J. (2017). Online Behavioral Advertising: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Advertising, 46(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2017.1339368

Boeschoten, L., Ausloos, J., Moeller, J., Araujo, T., & Oberski, D. L. (2020). Digital trace data collection through data donation. ArXiv:2011.09851 [Cs, Stat]. http://arxiv.org/abs/2011.09851

Bol, N., Dienlin, T., Kruikemeier, S., Sax, M., Boerman, S. C., Strycharz, J., Helberger, N., & de Vreese, C. H. (2018). Understanding the Effects of Personalization as a Privacy Calculus: Analyzing Self-Disclosure Across Health, News, and Commerce Contexts†. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23(6), 370–388. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmy020

Bol, N., Helberger, N., & Weert, J. C. M. (2018). Differences in mobile health app use: A source of new digital inequalities? The Information Society, 34(3), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2018.1438550

Bol, N., Strycharz, J., Helberger, N., Velde, B., & Vreese, C. H. (2020). Vulnerability in a tracked society: Combining tracking and survey data to understand who gets targeted with what content. New Media & Society, 22(11), 1996–2017. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820924631

Calo, M. R. (2013). Digital Market Manipulation. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2309703

Carballo-Calero, P. F. (2016). Aggressive Commercial Practices in the Case Law of EU Member States. Journal of European Consumer and Market Law, 255–261.

Caronna, F. (2018). Tackling aggressive commercial practices: Court of Justice case law on the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive ten years on. European Law Review, 43(6), 880–903.

Cauffman, C., & Goanta, C. (2021). A New Order: The Digital Services Act and Consumer Protection. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2021.8

Dance, G. J., LaForgia, M., & Confessore, N. (2018, December 18). As Facebook raised a privacy wall, it carved an opening for tech giants. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/18/technology/facebook-privacy.html

Dinev & Hart. (2006). Privacy Concerns and Levels of Information Exchange: An Empirical Investigation of Intended e-Services Use. E-Service Journal, 4(3), 25. https://doi.org/10.2979/esj.2006.4.3.25

Duivenvoorde, B. (2013). The Protection of Vulnerable Consumers under the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive. Journal of European Consumer and Market Law, 69–79.

Duivenvoorde, B. (2015). The Consumer Benchmarks in the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (Vol. 5). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13924-1

Duivenvoorde, B. (2019). The Upcoming Changes in the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive: A Better Deal for Consumers? Journal of European Consumer and Market Law, 219–228.

Esteller-Cucala, M., Fernandez, V., & Villuendas, D. (2019). Experimentation Pitfalls to Avoid in A/B Testing for Online Personalization. Adjunct Publication of the 27th Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization - UMAP’19 Adjunct, 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1145/3314183.3323853

European Commission. (2016). Guidance on the implementation/application of Directive 2005/29/EC on unfair commercial practices (Commission Staff Working Document, SWD(2016. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52016SC0163

European Commission. (2020). Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on a Single Market For Digital Services (Digital Services Act) and amending Directive 2000/31/EC. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=COM%3A2020%3A825%3AFIN

Fassnacht, M., & Unterhuber, S. (2016). Consumer response to online/offline price differentiation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 28, 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.09.005

Finck, M. (2021). The limits of the GDPR in the personalisation context. Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition Research Paper, Research Paper No. 21-11. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3830304

Franck, J., & Purnhagen, K. (2014). Homo Economicus, Behavioural Sciences, and Economic Regulation: On the Concept of Man in Internal Market Regulation and its Normative Basis. In K. Mathis (Ed.), Law and Economics in Europe (pp. 329–365). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7110-9_13

Friestad, M., & Wright, P. (1994). The Persuasion Knowledge Model: How People Cope with Persuasion Attempts. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1086/209380

Galli, F. (2021). Online Behavioural Advertising and Unfair Manipulation Between the GDPR and the UCPD. In M. Ebers & M. Cantero Gamito (Eds.), Algorithmic Governance and Governance of Algorithms (Vol. 1, pp. 109–135). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50559-2_6

Gerards, J., & Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. (2020). Protected Grounds and the System of Non-Discrimination Law in the Context of Algorithmic Decision-Making and Artificial Intelligence. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3723873

Golson, J. (2016, May 20). Uber knows you’ll probably pay surge pricing if your battery is about to die. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2016/5/20/11721890/uber-surge-pricing-low-battery

Graves, C., & Matz, S. (2018, February 5). What marketers should know about personality-based marketing. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/05/what-marketers-should-know-about-personality-based-marketing

Hanson, J. D., & Kysar, D. A. (1999). Taking Behavioralism Seriously: Some Evidence of Market Manipulation. Harvard Law Review, 112(7), 1420. https://doi.org/10.2307/1342413

Hauser, J. R., Liberali, G. (Gui), & Urban, G. L. (2014). Website Morphing 2.0: Switching Costs, Partial Exposure, Random Exit, and When to Morph. Management Science, 60(6), 1594–1616. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1961

Helberger, N., Lynskey, O., Micklitz, H.-W., Rott, P., Sax, M., & Strycharz, J. (2021). EU consumer protection 2.0: Structural asymmetries in digital consumer markets [Position Paper]. BEUC. The European Consumer Organisation. https://www.beuc.eu/publications/beuc-x-2018-080_ensuring_consumer_protection_in_the_platform_economy.pdf

Hill, R. P., & Sharma, E. (2020). Consumer Vulnerability. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 30(3), 551–570. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1161

Hirsh, J. B., Kang, S. K., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2012). Personalized Persuasion: Tailoring Persuasive Appeals to Recipients’ Personality Traits. Psychological Science, 23(6), 578–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611436349

Kosinski, M., Stillwell, D., & Graepel, T. (2013). Private traits and attributes are predictable from digital records of human behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(15), 5802–5805. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1218772110

Leerssen, P., Ausloos, J., Zarouali, B., Helberger, N., & de Vreese, C. H. (2019). Platform Ad Archives: Promises and Pitfalls. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3380409

Loos, M. B. M. (2019). The Modernization of European Consumer Law: A Pig in a Poke? European Review of Private Law, 113–134.

Malgieri, G. (2019). Automated decision-making in the EU Member States: The right to explanation and other “suitable safeguards” in the national legislations. Computer Law & Security Review, 35(5), 105327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2019.05.002

Marengo, D., & Montag, C. (2020). Digital Phenotyping of Big Five Personality via Facebook Data Mining: A Meta-Analysis. Digital Psychology, 1(1), 52–64. https://doi.org/10.24989/dp.v1i1.1823

Maslowska, E., Putte, B. van den, & Smit, E. G. (2011). The Effectiveness of Personalized E-mail Newsletters and the Role of Personal Characteristics. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(12), 765–770. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0050

Matz, S. C., Kosinski, M., Nave, G., & Stillwell, D. J. (2017). Psychological targeting as an effective approach to digital mass persuasion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(48), 12714–12719. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1710966114

McDonald, A. M., & Cranor, L. F. (2010). Americans’ attitudes about internet behavioral advertising practices. Proceedings of the 9th Annual ACM Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society - WPES ’10, 63. https://doi.org/10.1145/1866919.1866929

Micklitz, H.-W., Stuyck, J., Terryn, E., & Borghetti, J.-S. (Eds.). (2010). Cases, materials and text on consumer law. Hart.

Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (last). (2020). Leidraad bescherming van de online consument [Report]. https://www.acm.nl/sites/default/files/documents/2020-02/acm-guidelines-on-the-protection-of-the-online-consumer.pdf

Office Fair Trading. (2013). Personalised pricing: Increasing transparency to improve trust (OFT 1489). https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20140402165101/http:/oft.gov.uk/shared_oft/markets-work/personalised-pricing/oft1489.pdf

Park, G., Schwartz, H. A., Eichstaedt, J. C., Kern, M. L., Kosinski, M., Stillwell, D. J., Ungar, L. H., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2015). Automatic personality assessment through social media language. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(6), 934–952. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000020

P.H.D. Media. (2013, February 10). New Beauty Study Reveals Days, Times And Occasions When U.S. Women Feel Least Attractive. PR Newswire. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/new-beauty-study-reveals-days-times-and-occasions-when-us-women-feel-least-attractive-226131921.html

Poort, J., & Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. J. (2019). Does everyone have a price? Understanding people’s attitude towards online and offline price discrimination. Internet Policy Review, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.1.1383

Reich, N. (2016). Economic law, consumer interests, and EU integration. In K. Tonner, H. Micklitz, & P. Rott (Eds.), European consumer law. Intersentia.

Savin, A. (2021). The EU Digital Services Act: Towards a More Responsible Internet. https://research.cbs.dk/en/publications/the-eu-digital-services-act-towards-a-more-responsible-internet

Savova, D., Mikes, A., & Cannon, K. (2021). The Proposal for an EU Digital Services Act — A closer look from a European and three national perspectives: France, UK and Germany. Computer Law Review International, 22(2), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.9785/cri-2021-220203

Schumann, J. H., von Wangenheim, F., & Groene, N. (2014). Targeted Online Advertising: Using Reciprocity Appeals to Increase Acceptance among Users of Free Web Services. Journal of Marketing, 78(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.11.0316

Segalin, C., Perina, A., Cristani, M., & Vinciarelli, A. (2017). The Pictures We Like Are Our Image: Continuous Mapping of Favorite Pictures into Self-Assessed and Attributed Personality Traits. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 8(2), 268–285. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAFFC.2016.2516994

Smit, E. G., Van Noort, G., & Voorveld, H. A. M. (2014). Understanding online behavioural advertising: User knowledge, privacy concerns and online coping behaviour in Europe. Computers in Human Behavior, 32, 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.11.008

Smith, N. C., & Cooper-Martin, E. (1997). Ethics and Target Marketing: The Role of Product Harm and Consumer Vulnerability. Journal of Marketing, 61(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299706100301

Steppe, R. (2017). Online price discrimination and personal data: A General Data Protection Regulation perspective. Computer Law & Security Review, 33(6), 768–785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2017.05.008

Strycharz, J., Smit, E., Helberger, N., & van Noort, G. (2021). No to cookies: Empowering impact of technical and legal knowledge on rejecting tracking cookies. Computers in Human Behavior, 120, 106750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106750

Strycharz, J., van Noort, G., Helberger, N., & Smit, E. (2019). Contrasting perspectives – practitioner’s viewpoint on personalised marketing communication. European Journal of Marketing, 53(4), 635–660. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-11-2017-0896

Susser, D., Roessler, B., & Nissenbaum, H. (2019). Technology, autonomy, and manipulation. Internet Policy Review, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.2.1410

Tiku, N. (2017, May 21). Get Ready for the Next Big Privacy Backlash Against Facebook. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2017/05/welcome-next-phase-facebook-backlash/

Tran, T. P. (2017). Personalized ads on Facebook: An effective marketing tool for online marketers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 39, 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.06.010

Trzaskowski, J. (2013). The Unfair Commercial Practices Directive and vulnerable consumers. Paper for the 14th Conference of the International Association of Consumer Law 2013.

Trzaskowski, J. (2016). Lawful Distortion of Consumers’ Economic Behaviour – Collateral Damage Under the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive. European Business Law Review, 25–49.

Tufekci, Z. (2014). Engineering the public: Big data, surveillance and computational politics. First Monday. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v19i7.4901

Twigg-Flesner, C. (2018). Bad Hand? The “New Deal” for EU Consumers. Zeitschrift Für Das Privatrecht Der Europäischen Union, 15(4), 166–175. https://doi.org/10.9785/gpr-2018-150404

Van Boom, W. H. (2016). Unfair commercial practices. In C. Twigg-Flesner (Ed.), Research Handbook on EU Consumer and Contract Law. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781782547372

Veale, M., & Edwards, L. (2018). Clarity, surprises, and further questions in the Article 29 Working Party draft guidance on automated decision-making and profiling. Computer Law & Security Review, 34(2), 398–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2017.12.002

Vesanen, J., & Raulas, M. (2006). Building bridges for personalization: A process model for marketing. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 20(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20052

Wachter, S. (2021). Affinity Profiling and Discrimination By Association in Online Behavioral Advertising. Berkeley Technology Law Journal, 35(2). https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38JS9H82M

Ward, K. (2018). Social networks, the 2016 US presidential election, and Kantian ethics: Applying the categorical imperative to Cambridge Analytica’s behavioral microtargeting. Journal of Media Ethics, 33(3), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/23736992.2018.1477047

Weiner, J. (2014, December 22). Is Uber’s surge pricing fair?. The Washington Post. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/she-the-people/wp/2014/12/22/is-ubers-surge-pricing-fair/?noredirect=on

Willis, L. (2020). Deception by design. Harvard Journal of Law & Technology, 34(1). http://jolt.law.harvard.edu/assets/articlePDFs/v34/3.-Willis-Images-In-Color.pdf

Wolk, A., & Ebling, C. (2010). Multi-channel price differentiation: An empirical investigation of existence and causes. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 27(2), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2010.01.004

Zarouali, B., Dobber, T., De Pauw, G., & de Vreese, C. (2020). Using a Personality-Profiling Algorithm to Investigate Political Microtargeting: Assessing the Persuasion Effects of Personality-Tailored Ads on Social Media. Communication Research, 009365022096196. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220961965

Zarsky, T. Z. (2019). Privacy and Manipulation in the Digital Age. Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 20(1), 157–188. https://doi.org/10.1515/til-2019-0006

Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. (2020). Price Discrimination, Algorithmic Decision-Making, and European Non-Discrimination Law. European Business Law Review, 401–422.

Zuiderveen Borgesius, F., Kruikemeier, S., C Boerman, S., & Helberger, N. (2017). Tracking Walls, Take-It-Or-Leave-It Choices, the GDPR, and the ePrivacy Regulation. European Data Protection Law Review, 3(3), 353–368. https://doi.org/10.21552/edpl/2017/3/9

Zuiderveen Borgesius, F., & Poort, J. (2017). Online Price Discrimination and EU Data Privacy Law. Journal of Consumer Policy, 40(3), 347–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-017-9354-z

Add new comment