Counter-terrorism in Ethiopia: manufacturing insecurity, monopolizing speech

Abstract

For nearly three decades, Ethiopia’s current ruling party, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), has maintained its power through a highly centralized, vanguard party system. Recently, the Ethiopian government has extensively used the provisions of the Ethiopian Anti-Terrorism Proclamation (EATP) to prosecute several Ethiopian citizens and organizations that are critical of the ruling party. By framing the adoption and execution of the EATP as an outcome of EPRDF’s long-term hegemonic project coalesced in neopatrimonialism, this paper demonstrates how the Ethiopian State has created a rational-legal bureaucracy that exploits terrorism narratives to stifle critical speech on digital as well as traditional media. The result is the making of an online public that is unsure of what could be considered as a “terrorist” message as opposed to “normal” speech, who, in an attempt to not take the risk altogether, may avoid participating in political discourse. While the disbandment of the neopatrimonial order is key in dislodging Ethiopia’s legislative bottlenecks to civic liberties, a more urgent task calls for a move toward participatory, inclusive, and equitable Internet policy framework.This paper is part of Practicing rights and values in internet policy around the world, a special issue of Internet Policy Review guest-edited by Aphra Kerr, Francesca Musiani, and Julia Pohle.

Introduction

The potential of the internet as a site of protest, resistance, and social change in the context of repressive regimes has been the subject of scholarly inquiry in the past two decades (Baron, 2009; Castells, 2012; Cowen, 2009; Fenton, 2016; Pohle & Audenhove, 2017; Shirky, 2008). From the printing press to the internet, the transformative power of new communication technologies lies in their tendency to disrupt central authority and control. When faced with disruptive communication technologies, authoritarian governments’ knee-jerk reaction is usually one of confusion, suspicion, and prohibition. However, repressive regimes also learn to embrace these technologies with the aim of strengthening the existing order (Kalathil & Boas, 2003; Morozov, 2013). For example, McKinnon’s (2011) notion of “networked authoritarianism” reflects how authoritarian regimes in countries like China not only adopt new communication technologies but also use these technologies to bolster their legitimacy. While some of the most widespread practices of using the internet as a means of control include surveillance (Fuchs & Trottier, 2017; Grinberg, 2017), censorship (Akgül & Kırlıdoğ, 2015; Yang, 2014), and hacking (Gerschewski & Dukalskis, 2018; Kerr, 2018), these practices are oftentimes informed by internet policy frameworks and rational-legal dynamics. As Hintz and Milan (2018) articulate, the institutionalisation and normalisation of surveillance practices into law and popular imagination in Western democracies indicates authoritarian repurposing of the internet is now a global phenomenon.

Through a case study of Ethiopia, this paper attempts to shed some light on how the rise of counter-terrorism legal frameworks shape a nation state’s internet policy, especially as it pertains to communication of dissent, resistance, and protest. Consistent with global trends in response to acts of terrorism, the Ethiopian government adopted a counter-terrorism legislation in 2009. While this legislation was championed by the Ethiopian government as a way of combating terrorism, its adoption as arguably the most consequential legal framework in undermining freedom of expression is akin to the neopatrimonial rational-legal design of the ruling party, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). Neopatrimonialism, Clapham (1985) notes, is “a form of organisation in which relationships of a broadly patrimonial type pervade a political and administrative system which is formally constructed on rational-legal lines” (p. 48). Neopatrimonial governments are organised through modern bureaucratic principles with formally defined powers although these powers are exercised “as a form of private property” (Ibid.).

In this paper, I discuss how the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation of 2009 (hereafter referred to as “the EATP” or “the Proclamation”) has been appropriated to stifle freedom of expression involving mediated communication, especially in digital platforms. The study relies on a policy review of the EATP and other supplementary legal frameworks to assess provisions affecting digital freedoms, internet governance frameworks and political expression. In examining EPRDF’s adoption and use of a counter-terrorism legal framework, I situate my discussion within the neopatrimonial state framework. Drawing on literature that critically examines the corrosive impact of counter-terrorism laws on freedom of expression globally, I analyse how the EATP has severely undermined civil liberties of expression. In doing so, I demonstrate how the law affected digital freedoms as well as other pillars of a democratic polity such as journalistic practice. I conclude by highlighting the implications of the Proclamation in projecting a highly restrictive Ethiopian internet policy framework as it pertains to regulation and surveillance.

The global rise of counter-terrorism laws

The terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 in the US, as well as other similar incidents in different parts of the world have caused profound changes in political, economic, and social relations globally. From communication systems to immigration flows to financial transactions, nations have aggressively sought a wide range of mechanisms to proactively curb potential threats (Birkland, 2004; Croucher, 2018). While executive branches such as law enforcement bodies and even militaries are commonly part of the counter-terrorism apparatus, the most conspicuous common denominator across nations has been the rise of what came to be known as counter-terrorism laws (De Frias, Samuel, & White, 2012).

The recent prominence of counter-terrorism laws across the world has had significant implications to the study of global terrorism from legal and policy perspectives, especially in terms of determining what constitutes (and does not) an act of terrorism. In this regard, the lack of a universal definition of terrorism is not only unsurprising but may also be an impossible task. Although such fluidity of the term is not new, the executive delimitation of terrorism has been conditioned by Resolution 1373 of the United Nations Security Council that was issued on 28 September 2001 following the terrorist attacks on the US earlier that month. The Resolution, among other things, called nations to criminalise acts of terrorism as well as financing, planning, preparation and support for terrorism. In order to expedite the directive, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) created a new Counter-Terrorism Committee that was tasked with overseeing counter-terrorism actions adopted by member states. While the resolution directed member states to step-up their counter-terrorism efforts, it did not provide a framework to define what constitutes an act of terrorism. Roach et al. (2012) note that this has left individual nations to define terrorism according to their contextual concerns. This approach is not unexpected given how international counter-terrorism law and policy involve multiple layers of actors and stakeholders as well as “interplay between international, regional and domestic sources of law” (Roach, Hor, Ramaj, & Williams, 2012, p. 3).

One of the consequences of the rather elastic framing of terrorism coupled with the rise of counter-terrorism laws across nation states has brought renewed concerns about infringement of basic human rights. Well known post-9/11 counter-terrorism activities in Guantanamo Bay or American “black sites” in some European countries (secret prisons mostly operated by the CIA where inmates have no rights other than those afforded to them by their detainers) as well as rendition sites in countries like Egypt have demonstrated there is a thin line between curbing terrorist acts and violating the basic right to be free from torture and degrading treatment (Setty, 2012). In addition to concerns over torture and degrading treatment, counter-terrorism efforts have also ignited debate on striking the right balance between thwarting terrorism and ensuring expressive, associational and assembly freedoms (Schneiderman & Cossman, 2002). Of critical importance here is how UNSC-endorsed counter-terrorism laws have created an added impetus for authoritarian governments to criminalise legitimate forms of domestic dissent (Roach, 2015).

Because of their reactive posture, counter-terrorism laws are closely linked with state securitisation. Securitisation, however, is subject to misperception in its framing of disorder. In many instances, as Bergson (1998) notes, disorder can be a construct of the state emanating from a contradiction between one’s own interests or needs. In this sense, securitisation generates insecuritisation by creating fear, which in turn empowers the state to expand its control. As Karatzogianni and Robinson (2017) highlight, securitisation “involves framing-out any claims, demands, rights or needs, which might be articulated by non-state actors. Such actors are simply disempowered, and either suppressed and ‘managed’ or paternalistically ‘protected’” (p. 287). By reducing social problems and differences to security issues, securitisation considerably expands state power by creating emergencies to combat imagined “dangers” (Bigo, 2000; Freedman, 1998; Gasteyger, 1999). In tandem with this securitisation rationale, many authoritarian and quasi-authoritarian states have aligned themselves with what came to be loosely known as the “war against terrorism” global front. However, these states have intensified the use of counter-terrorism apparatus, including legislative means, to revamp internet policy frameworks, which in turn have direct ramifications to civic liberties.

It should be noted that concerns over appropriating counter-terrorism legal frameworks for authoritarian ends is not a uniquely Ethiopian phenomenon. For example, Egypt adopted its own version of counter-terrorism law in 2015 that significantly curbed rights of freedoms of assembly, association and expression. Formally referred to as the Law of Organising the Lists of Terrorist Entities and Terrorists, Egypt’s counter-terrorism legislation gives mandate to the government to legally exercise surveillance over Egyptians as well as penalise those who oppose or criticise state policies and practices. Egypt’s counter-terrorism law has been criticised for criminalising dissent, usually through conflating crimes committed by violent groups to peaceful acts of expression that are critical to the government. By employing vague language that is prone to arbitrary interpretation, Hamzawy (2017, p.17) notes that the terrorism law “does not require the government’s accusations of terrorist involvement to be proven through transparent judicial proceedings before individuals are placed on the list.”

Another African country that has adopted a counter-terrorism law recently with controversial outcomes is Cameroon. The Law on the Suppression of Acts of Terrorism in Cameroon (No. 2014/028) was enacted in 2014 against a backdrop of an initiative to contain threats from designated terrorist organisations, most notably Nigeria’s Islamist Jihadist group, Boko Haram. While the law won notable support originally, its eventual deployment raised serious concerns over infringement of rights of expression protected under the Cameroonian Constitution and international human rights law. According to a report by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) (2017, p.7), the counter-terrorism legislation has been especially criticised for penalising journalists by conflating “news coverage of militants or demonstrators with praise,” resulting in journalists not knowing “what they can and cannot report safely, so they err on the side of caution.” One of the most notable cases involved Radio France Internationale (RFI) journalist Ahmed Abba, who is serving a ten-year prison sentence on terrorism charges for his reporting on the militant group Boko Haram after he was convicted by a military tribunal of “non-denunciation of terrorism” and “laundering of the proceeds of terrorist acts” (CPJ, 2017, p. 7).

Ethiopia, EPRDF and counter-terrorism

The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE) has been ruled by EPRDF since 1991. A coalition of four ethnically organised political parties, EPRDF instituted a highly centralised, top-down administration structure that championed an ethno-nationalist political programme (Gashaw, 1993; Gudina, 2007; Habtu, 2003). Although EPRDF’s administrative lifespan projects a nominal democratic façade of elections, its legitimacy to govern has been called into question several times (Aalen & Tronvoll, 2009; Lyons, 2016). In the most recent national elections of 2015, for example, EPRDF declared victory over every parliamentary seat to extend its already protracted longevity. For the second most populous country in Africa that holds contested ethnic, ideological, cultural, and political worldviews, EPRDF’s complete dominance in the rational-legal apparatus of the Ethiopian state has been anything but representative of the Ethiopian public.

In its 28 years’ dominance of the Ethiopian government, EPRDF carried out several mechanisms of quelling alternative political ideologies as well as the individuals and organisations that express them. The mechanisms through which EPRDF strived for political monism that guarantees its supremacy range from outright human rights violations to ideological warfare (Allo, 2017; Gudina, 2011; Kidane, 2001; Tronvoll, 2008). Arguably, the most common strategy EPRDF deployed to assert its power involved the mobilisation of its security and executive apparatus to go after political dissidents who were reportedly imprisoned, exiled, harassed, disappeared or died (Di Nunzio, 2014; Gudina, 2011; Vestal, 1999). Secondly, EPRDF was involved in a mass ideological indoctrination of its political programme (Abbink, 2017; Arriola & Lyons, 2016). Across federal and state government offices, state-owned enterprises, and state-run higher education institutions, devotion to the ideals of EPRDF’s abyotawi dimokrasi 1 became the definitive rubric for reward and punishment. As former Prime Minister of Ethiopia and author of EPRDF’s political-cum-economic programme, Meles Zenawi believed, the long-term success of his party was contingent on the successful branding of “developmentalism” 2 and the creation of a mass devoted to it (Fana, 2014; Matfess, 2015). Thirdly, EPRDF was accused of fostering a state-sponsored social engineering of the Ethiopian people through an ethnic federalism design. By forging regional states along ethnic fault lines, EPRDF, despite its unpopularity, managed to sustain its political longevity through a divide-and-rule strategy that created mistrust and animosity between different ethnic groups (Bélair, 2016; Mehretu, 2012). Fourthly, and crucial to the current study, EPRDF laid out a neopatrimonial rational-legal network where state resources were systematically channelled for party interests (Kelsall, 2013; Weiss, 2016). This created a blurring of the demarcation between party and government, resulting in the rise of, among other things, a justice system that is loyal to EPRDF interests. It is this neopatrimonial interlocks between the Ethiopian legislative and judiciary organs coupled with global shifts in counter-terrorism strategies that cultivated the necessary conditions for the introduction of the EATP 2009.

An influential player in geopolitical and diplomatic affairs of the African continent, the FDRE is a key ally to the US in combating terrorism and terrorist groups in the Horn of Africa. The US and FDRE have established multiple counter-terrorism partnerships that specifically target designated terrorist groups such as Al Shabab in neighbouring Somalia (for example, see Agbiboa, 2015). In spite of its abysmal human rights record, especially between 2005-2018, Ethiopia continued to be regarded highly by the US and its allies due to the strategic alliance it offers in combating terrorism. Nevertheless, for Ethiopia’s ruling party, this partnership is as much about combating terrorism as it is about extending its grip on political power which has now lasted for nearly three decades (Clapham, 2009). EPRDF has been accused of repurposing counter-terrorism apparatuses—intelligence and surveillance systems, military equipment, and technical knowhow—financed and set up by its Western allies to quell critical expression, organisation and assembly domestically (Turse, 2017). In spite of years of US Department of State country reports that document state-sponsored human rights abuses, the US continued to follow a policy of appeasement toward the Ethiopian government, possibly to avoid the disruption of its geopolitical priority in the region. In this sense, it is plausible to argue that EPRDF views this as a critical leverage, one that is aimed at keeping outside political interference at bay, thereby effectively silencing external pressures of political reform. In the interest of maintaining its strategic priorities, EPRDF’s Western partners have chosen to be “oblivious to or even ignorant of Ethiopia’s worsening political exclusivity” (Workneh, 2015, p. 103), allowing the former to, without meaningful accountability, undermine basic human rights under the guise of counter-terrorism efforts.

It is against this background that Ethiopia adopted a counter-terrorism legal framework in 2009 although, in prior years, it was already involved in other counter-terrorism activities including the US backed military campaign against the Al Qaeda affiliated Islamic Court Union (ICU) in 2006 (Rice & Goldenberg, 2007). Since its enactment by the EPRDF-dominated Ethiopian parliament, the EATP has been extensively used to prosecute hundreds of individuals that include journalists, opposition political party members, and civil society groups. 3 In many ways, the Ethiopian government’s actions since the adoption of the Proclamation in 2009 justified concerns of human rights groups who have heavily criticised the law for being dangerously vague in framing terrorist acts, violating international human rights law, and dismantling criminal justice due process standards. Some observers highlight the EATP has become the most potent tool to stifle legitimate forms of critical expression, organisation, and assembly (Kibret, 2017; Sekyere and Asare, 2016).

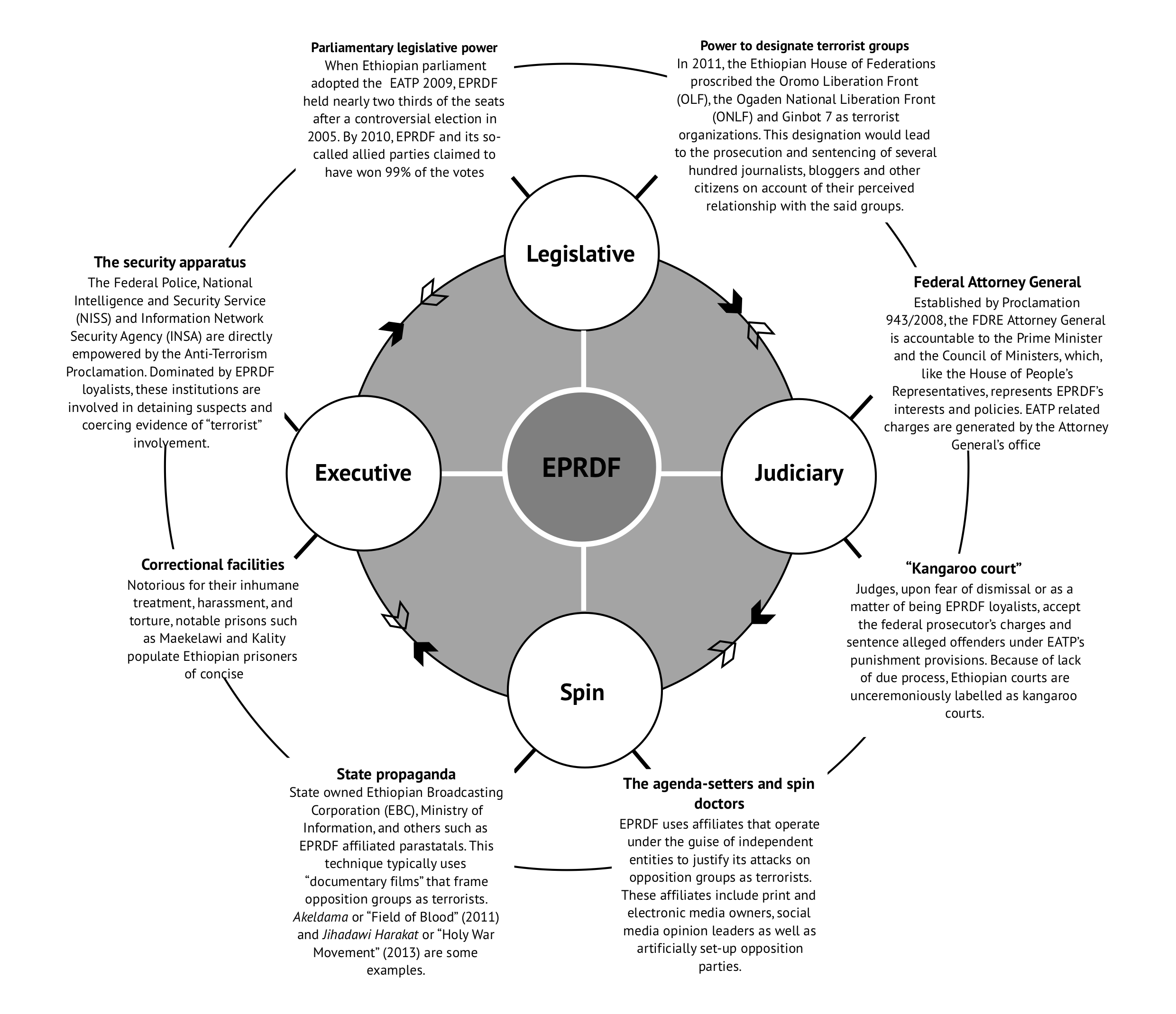

The fatal consequences of Ethiopia’s adoption of a counter-terrorism framework to freedom of speech was mostly predictable because of the Ethiopian government’s poor track record on human rights. Several nations’ rush to adopt counter-terrorism laws has been motivated by the idea of creating a lawful means to bypass existing criminal justice procedures that may not be speedy or effective enough to respond to national security threats (Daniels, Macklem, & Roach, 2012). In this sense, counter-terrorism laws empower governments to exercise a “state of exception” where, under perceived or real terrorism threats, normal procedures of jurisprudence in criminal law may be circumvented in the spirit of upholding “the greater good.” As Roach et al. (2012, p. 10) succinctly summarised, the intent here is “accommodating terrorism and emergencies within the rule of law without producing permanent states of emergency and exception.” It is plausible to perceive, without overlooking critical loopholes, how countries with established democratic traditions would have better institutional mechanisms to combat corrosive uses of counter-terrorism laws. In a democratically fragile country like Ethiopia where all branches of government including the judiciary are set up to buttress the self-proclaimed hegemonic project of the ruling party, the EATP has become the rule and not the exception (see Fig. 1 for EPRDF’s neopatrimonial interlocks in the context of the EATP).

Situating the Ethiopian counter-terrorism law apparatus under the neopatrimonial state framework

The anocratic design of the Ethiopian state has effectively created a monopoly of governance by EPRDF. 4 Through a rational-legal system that resembles a democratic polity but which, in practice, enables the continuity of a one-party rule, EPRDF has projected itself as a vanguard elite of democracy and development in Ethiopia. For critics, however, EPRDF’s Ethiopia is neither developmental nor democratic, but rather a neopatrimonial state that lodged a complex rational-legal bureaucracy to appropriate public resources into the group and individual interests of the ruling elite.

The concept of neopatrimonialism essentially encompasses a dualistic nature where “the state is characterized by patrimonialisation and bureaucratization” [sic.] (Bach, 2011, p. 277). This fusion, a quintessential characteristic of the neopatrimonial state, assumes a scenario where the “patrimonial logic coexists with the development of bureaucratic administration and at least the pretence of rational-legal forms of state legitimacy” (Van de Walle, 1994, p. 131). Such dualism can effectively translate into a wide array of empirical situations. These mirror variations in the state’s failure or capacity to produce “public” policies. Neopatrimonialism, in this sense, is a modern, sophisticated form of patrimonialism in which “patrimonial logic coexists with the development of bureaucratic administration and at least the pretense of rational-legal forms of state legitimacy” (Van de Walle, 1994, p. 131).

Davies (2008) incorporates two key features of neopatrimonial governance. Firstly, the neopatrimonial state personalises political authority significantly both as an ideology and as an instrument. Secondly, such governments develop a conflicting rational-legal bureaucratic system and clientelistic relations, with the latter usually dominating over the former. A number of scholars treat clientelism and patronage as integral components of neopatrimonialism (Bratton & van de Walle, 1994; Erdmann & Engel, 2007; Eisenstadt, 1973). Clientelism represents “the exchange or brokerage of specific services and resources for political support, often in the form of votes” involving “a relationship between unequals, in which the major benefits accrue to the patron” and “redistributive effects are considered to be very limited” (Erdmann and Engel, 2007, p. 107). In a broad sense, it is the complexity and sophistication of this “brokerage” that distinguishes neopatrimonial clientelism from patrimonial clientelism. Unlike the “direct dyadic exchange relation between the little and the big man” (Erdmann & Engel, 2007, p. 107) that is characteristic of patrimonialism, the neopatrimonial state needs a network of brokers that have permeated into a bureaucratic nexus where they can render the interest of the political center to the periphery (Powell, 1970; Weingrod, 1969).

Making sense of the EATP as a neopatrimonial instrument of control

In the Ethiopian context, a recent example of how the rational-legal bureaucracy is upended along neopatrimonial lines is indicated by the adoption of the EATP in 2009. Although the Proclamation was conceived as a means by which the Ethiopian state could legally circumvent existing laws of criminal justice—which is commonly practiced in other countries with similar legal frameworks—recent trends indicate the Proclamation has been excessively used to criminalise domestic political opposition and critical speech. In the following, I will address how the EATP was used not as a security tool but rather as a means of safeguarding the ruling party’s dominance in three ways: (a) curbing digital freedoms; (b) monopolising the political narrative; and (c) manufacturing fear to incubate self-censorship.

Curbing digital freedoms

One of the ways the EATP set itself up as a legal framework with substantial ramifications for freedom of expression is related to its determination of what it deems to be evidences of terrorist acts. Specifically, the law’s focus on “digital evidence” warrants critical scrutiny in relation to its implications to digital expressions of dissent and resistance. For example, Villasenor (2011) demonstrates how digital storage enables authoritarian governments to track organised dissent online. Hellmeier (2016), who surveyed determinants of internet filtering as measured by the Open Net Initiative in 34 autocratic regimes, outlines digital toolkits available to autocrats to control political activism on the internet. Dripps (2013) warns about the risks posed on privacy when unchecked access to digital evidences may lead to the exposition of “innocent and intimate information” of individuals (p. 51). Against this backdrop of authoritarian governments’ use of digital artifacts to stifle critical speech, the EATP’s definition of “digital evidence” poses a palpable risk to communication of dissent, protest or resistance:

[Digital evidence refers to] information of probative value stored or transmitted in digital form that is any data, which is recorded or preserved on any medium in or by a computer system or other similar device, that can be read or perceived by a person or a computer system or other similar device, and includes a display, printout or other output of such data (FDRE, 2009, p. 4829).

While this definition by itself may be fairly acceptable in everyday use of the language, it warrants special scrutiny in terms of what it entails in a counter-terrorism context. In tandem with the overall characteristic of the legislation, the broad definition of “digital evidence” leaves a vast latitude of interpretive discretion to judiciary and executive branches of the government. In the Ethiopian context, the extensive neopatrimonial interlocks between the legislative body that adopted the EATP, the judiciary that interprets the law, and the executive branch that carries out punishments have undermined the credibility of due process. When seen against the neopatrimonial roots of the EATP, the oppressive conceptualisation of “digital evidence” are evident in three ways: information storage; transmission, and consumption.

The information storage imperative poses a threat to digital freedoms because, at its core, it is an attempt to dissolve the notion of communication devices such as computers, cell phones, storage drives as private entities. The mobile phone or the computer is not only an information processing device, but a physical space where individuals purposefully (documents, pictures, audio, video, etc.) or inadvertently (cookies, search history, catches, etc.) store crucial information that enables them to archive different aspects of their livelihood. It gives them control over memory by enabling a sense of permanence. In this sense, the individual’s communication device has become an extension of private personhood (Conger, Pratt, & Loch, 2013; Kotz, Gunter, Kumar, & Weiner, 2016; Weber, 2010).

It should be noted that government encroachment on private digital spaces, especially through information extraction, is neither unusual nor uniquely Ethiopian. 5 In 2016, for example, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in the US has asked Apple to help unlock an iPhone belonging to a shooter responsible to the death of 14 people in San Bernardino, California (Nakashima, 2017). The case ended up in court because Apple declined to help the FBI by arguing developing software to access the phone would be used in several other instances, thereby endangering encryption and data privacy altogether. In 2015, the New York Times reported how pro-Syrian government hackers targeted cellphones and computers of rebel fighters in an attempt to extract the latter’s contacts and operations (Sanger & Schmitt, 2015). In examining the Ethiopian case, the goal of state-sponsored encroachment of the private digital space is consistent with other similar practices globally, i.e., the case for information extraction. However, Ethiopia offers a compelling case of an attempt to institutionalise the de-personalisation of the private communication device through a counter-terrorism legal framework that is arguably designed for non-counter-terrorism acts of political dissent. The nebulous designation of digital evidence as “information of probative value” has indeed resulted in the prosecution of several individuals charged under the counter-terrorism law. 6

Extensive policing over communication technology devices by the Ethiopian government has been a common practice. For example, until recently, the government requires citizens to register their laptops with the Ethiopian Customs Authority before they could travel out of the country. so that they won’t bring new devices in upon return. Between 2017-2018, Ethio-Telecom, the state-owned telecommunications operator which has monopoly over voice, text, and data services in Ethiopia, required citizens to register their phones with the company in order to obtain service. Any phone that was not registered would not get access to telecommunication services in Ethiopia. It is within this already hostile ICT environment that the government, through the EATP, moved to dismantle citizens’ reasonable expectation that their communication devices are private. Several journalists, bloggers, opposition party members report how the government confiscates their mobile phones and personal computers in its “arrest first, find evidence later” approach. Sileshi Hagos is a good case in point here. He was briefly detained and interrogated by government security forces about his fiancé Reeyot Alemu, a journalist who was imprisoned under terrorism charges for her alleged communication with the banned and terrorist designee opposition party Ginbot 7 (Sreberny, 2014). 7 The government confiscated his laptop, presumably to extract information related to his and Reeyot Alemu’s alleged communication with Ginbot 7 (Pen International, 2011).

While the EATP’s designation of “storage” as an important element of “digital evidences” empowers the government to encroach on personal communication devices, perhaps the more dangerous way in which the law sets the state up to dissolve individual privacy rights is conditioned by the government’s newfound legal status to use information intercepted from communication exchanges in the digital sphere. While the EATP’s provision of the Ethiopian intelligence apparatus with legal protection to eavesdrop on citizens’ communication curbs privacy rights, 8 the more dangerous provision involves the authorisation of mass surveillance through communication service providers. The EATP’s stipulation that “any communication service provider shall cooperate when requested by the National Intelligence and Security Service to conduct the interception” (FDRE, 2009, p. 4834) directly puts Ethio-Telecom, the sole telecommunication service provider in Ethiopia, as a site of unchecked mass surveillance. A massive state-owned monopoly in the telecommunications sector of Ethiopia with more than 59 million de facto clients (ITU, 2018b), Ethio-Telecom has been implicated in citizen monitoring in several instances. During the 2005 general elections, for example, the Ethiopian government ordered the state-owned telecommunication provider to shut down the SMS system after opposition groups successfully deployed text-based campaigns (Abdi & Deane, 2008). Horne & Wong (2014) detail how the Ethiopian government acquires surveillance technologies from several countries, and are then oftentimes integrated with Ethio-Telecom operations. This results in unrestricted access to call records, internet browsing logs, and instant messaging platforms (Marquis-Boire, Marczak, Guarnieri, & Scott-Railton, 2013). In 2015, a massive online data dump involving the Italian commercial surveillance company, Hacking Team, showed numerous evidences including email transcripts, invoices, and technical manuals that directly implicated the Ethiopian government. The Hacking Team’s surveillance products were used by Ethiopia’s Information Network Security Agency (INSA) to acquire communication involving journalists affiliated with Ethiopian Satellite Television (ESAT), a US and Europe based network known for its critical views on EPRDF’s rule (Currier & Marquis-Boire, 2015). In this sense, the EATP’s directive for communication providers in Ethiopia—Ethio-Telecom by default—to relinquish private information of users only formalises what many considered to be a long-standing exercise of institutional control of citizens’ communication.

In addition to Ethio-Telecom, this stipulation enables the Ethiopian National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) to require third-party communication service providers such as internet cafes to keep records of users’ online activities. Requiring third-party communication service providers to monitor and report users’ activities is not uncommon in other parts of the world. In the Ethiopian case, it is particularly concerning because the majority of users that rely on computers do not access the internet from their households but from third party public providers like internet kiosks, cafeterias, hotels, as well as schools.

The storage and transmission elements of “digital evidence” are compounded by the consumption component which directly implicates user behaviour. Under the “Failure to Disclose Terrorist Acts” section, the EATP stipulates, among other things, anyone who fails to disclose information or evidence that can be used to prosecute or punish a suspect involved in “an act of terrorism” will be punished with rigorous imprisonment (FDRE, 2009, p. 4832). The danger of this provision of the EATP lies in the parametric nebulousness of “an act of terrorism” which emanates from the contested conceptualisation of terrorism itself. If a journalist receives an email communication from one of the terrorist-designated Ethiopian political organisations and he/she keeps the name of the source anonymous as a matter of journalistic ethics, the EATP empowers the state to prosecute the journalist through the “Failure to Disclose Terrorist Acts” provision. For many journalists, the challenge here is the extensive popular support the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and Ginbot 7 enjoy compels them to report the organisations’ activities as a matter of public interest. For EPRDF, blacklisting these organisations serves the purpose of making them obsolete in the political arena. Journalists who transmit information regarding such organisations as OLF and Ginbot 7 in public discourse inevitably run the risk of being charged as terrorists or accomplices of terrorism.

Monopoly of political narrative

Although the various charges carried out under the premises of the EATP by the Ethiopian government differ in their scope and nature, a sizable number of the cases have serious implications for the state of freedom of expression, especially mediated critical speech. In this sense, it is of no surprise that the EATP has probably been put into retributive effect more than any other legal framework related to communication involving electronic media. Since its enforcement, the law has disproportionately targeted community members who are involved in the dissemination of information through traditional and digital media platforms, including bloggers, journalists, and freelance writers. In Ethiopian Satellite Television and Oromia Media Network v The Federal Public Prosecutor, US based television stations Ethiopian Satellite Television (ESAT) and Oromia Media Network (OMN) were accused of disseminating information deemed to be in the interest of the Ethiopian government designated terrorist groups Ginbot 7 and OLF. The underlying argument of the Federal Public Prosecutor was based on the assumption that disseminators of information involving terrorist-designated groups act as accessories of terrorism. The EATP renders a very broad and ambiguous language that criminalises speech deemed to be an “encouragement” of terrorism, whatever the latter may be, through the interpretive lens of the Ethiopian government. Consider Article 6 of the Proclamation:

Whosoever publishes or causes the publication of a statement that is likely to be understood by some or all of the members of the public to whom it is published as a direct or indirect encouragement or other inducement to them to the commission or preparation or instigation of an act of terrorism…is punishable with rigorous imprisonment from 10 to 20 years [emphasis mine] (FDRE, 2009, p. 4831).

When the determination of what encompasses an encouragement of a terrorism act is made based on the “likely” understanding of “members of the public”, the outcome warrants a scenario of arbitrary interpretation, jurisprudence, and execution of the law. In other words, by keeping the law as vague and broad as possible, the government can choose to use it haphazardly in order to stamp out legitimate acts of political expression and dissent. Consider, for example, the case of Reeyot Alemu Gobebo, former contributor of the weekly newspaper Feteh. She was convicted on three counts under the terrorism law for her writings that were highly critical of the ruling party and the former Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Meles Zenawi, who was persistent in his characterisation of members of the free press as “messengers” of terrorist groups (Abiye, 2011). Although Reeyot Alemu was formally convicted of having ties with terrorist groups—a common blanket accusation the Ethiopian government infers to arrest journalists and freelance writers—it is important to note that Reeyot Alemu and other journalists that were imprisoned with terrorism charges were targeted by the government for their continued journalistic practices that were viewed by EPRDF as divergent to its hegemonic rule (see CPJ, 2012; Dirbaba & O’Donnell, 2012).

In other words, when journalists such as Reeyot Alemu report about groups such as Ginbot 7 and OLF, their actions are justified based on the enormous public interest imperative that is at stake. If and when a journalist, according to the EATP, “publishes or causes the publication of” groups or individuals designated as terrorists by the Ethiopian government, they will run the very likely risk of being imprisoned. Everyday journalist routines of establishing a source, conducting an interview, or simply relaying a press release involving designated “terrorist organisations” can easily be prosecutable acts. 9

Manufacturing fear, fostering self-censorship

While the appropriation of the EATP to target media professionals by tying them to controversially terrorist designated political groups is in and of itself an attack on the freedom of expression enshrined in the Ethiopian Constitution, 10 the more dangerous consequence is probably the chilling effect this “example” has set for ordinary citizens. The indiscriminate use of “terrorist” to refer to journalists reporting on opposition groups has now evolved to include individuals whose political, economic, social or human rights opinions differ from EPRDF’s narrative. For example, Workneh (2015) notes how legal frameworks such as the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation adopted by the government have created a cloud of insecurity and fear in Ethiopian social media users when it comes to political opinions. The thin line between “dissent” and “terrorism” leads users to unwittingly undergo different forms of self-censorship in the digital sphere, a scenario that enables the government to create a subdued public that is reluctant in participating in a counter-hegemonic narrative.

This “fear factor” born out of the government’s criminalisation of critical speech is compounded by the EATP’s empowerment of the state with the authority to intercept communication that endows the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS), upon getting court warrant, to: intercept or conduct surveillance on the telephone, fax, radio, internet, electronic, postal and similar communications of a person suspected of terrorism; enter into any premise in secret to enforce the interception; or install or remove instruments enabling the interception. As indicated earlier in this article, the Federal Public Prosecutor has presented transcripts of phone conversations obtained through wiretapping by the government as evidence in a court of law in Soliana Shimeles et al. v the Federal Public Prosecutor. 11 The frequency in which the government infiltrates into the private communications of Ethiopian citizens—especially activists and journalists with critical opinions—has become a common practice since the EATP was put in place in 2009. 12

Conclusion

The adoption of legal frameworks such as the EATP that stipulate broad and vague definitions of terrorism, which, in turn, are used to frame critical speech as terrorist acts, are used to directly prosecute critics of the Ethiopian government. More importantly, however, it is sensible to argue that the Ethiopian government’s actions through the EATP could be seen as a long-term proactive strategy of creating a rational-legal bureaucracy—consistent with the neopatrimonial logic—that is subject to arbitrary interpretation and execution at the will of the state. The result is the making of a public that is unsure about what could be considered as a “terrorist” message as opposed to “normal” speech, which in turn incubates a widespread self-censorship culture. Consequently, the much-publicised prosecution of Zone 9 bloggers and other online political activists in Ethiopia through the EATP and other legal frameworks is not necessarily an exercise of stifling the views of the defendants per se, but rather what they represent in terms of a young, critical and digitally literate Ethiopian populace that is in the making.

As a practical matter, it is evident to see how the EATP compounds the highly restrictive internet policy frameworks in Ethiopia informed by such legal frameworks as the Telecom Fraud Offense Proclamation of 2012. Elsewhere, I argued how Ethiopia’s internet policy frameworks negatively affect user activity (Workneh, 2015), and outlined how the highly centralised, top-down, and monopolistic Ethiopian telecommunication policy adversely affected quality, access, and usability of digital platforms for Ethiopians (Workneh, 2018). 13 The outdated legislative frameworks that shape Ethiopia’s digital ensemble need a reboot. This recourse should envisage a shift from vanguard centralism to a participatory, multi-stakeholder, and equitable paradigm. Inclusive, people-centered internet policies have paid dividends to citizens of other African countries like Kenya, where the highly successful mobile finance platform m-pesa, for example, brought about tangible results in information justice and financial inclusion (see e.g. Jacob, 2016).

It is in this spirit that, as Ethiopia currently undergoes an uncertain political reform (Burke, 2018) that includes the ongoing scrutiny of its counter-terrorism legislation (Maasho, 2018), a cautions diagnosis of what to do with the EATP is paramount. One approach to address the corrosive outcomes of the EATP is to get rid of the law in its entirety. This view is not uncommon. Brownlie (2014) argues there should be no category of a law of terrorism and that terrorism cases should be conducted “in accordance with the applicable sectors of public international law: jurisdiction, international criminal justice, state responsibility, and so forth” (p. 713). The second approach is to keep the EATP by making significant revisions, especially in terms of provisions that have been identified as problematic to civil liberties. While an argument can be made for the merits and shortcomings of both, the execution of either approach doesn’t necessarily guarantee the right to freely express opinions. In my view, the EATP is one instrument of EPRDF’s multifaceted neopatrimonial apparatus. Without a comprehensive political reform that ensures genuine multi-stakeholder participation and the termination of the neopatrimonial order, any action against the EATP, noble as it may be, will fall short of a meaningful stride toward a free society. The most consequential provision of the EATP is not any of the language that directly curb freedom of expression but rather the Proclamation’s designation of a politically homogeneous legislative body to have the power to “proscribe and de-proscribe an organization as terrorist organization” [sic.] (FDRE, 2009, p. 4837). It is this very clause that has enabled the EPRDF-dominated Ethiopian House of Peoples’ Representatives to proscribe opposition groups and their supporters such as OLF, Ginbot 7, and ONLF as terrorists 14, which in turn led to the persecution of thousands of Ethiopians. If the Ethiopian government’s legislative body is truly representative of the diverse political spectrum of the country, a politically-motivated designation of dissenting individuals and organisations as terrorists is highly unlikely, thereby minimising the likelihood of a counter-terrorism legislation’s significance as an instrument of neopatrimonial control.

References

Aalen, L., & Tronvoll, K. (2009). The end of democracy? Curtailing political and civil rights in Ethiopia. Review of African Political Economy, 36(120), 193–207. doi:10.1080/03056240903065067

Abbink, J. (2017). Paradoxes of electoral authoritarianism: the 2015 Ethiopian elections as hegemonic performance. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 35(3), 303–323. doi:10.1080/02589001.2017.1324620

Agbiboa, D. (2015). Shifting the battleground: The transformation of Al-Shabab and the growing influence of Al-Qaeda in East Africa and the Horn. Politikon, 42(2), 177–194. doi:10.1080/02589346.2015.1005791

Akgül, M., & Kırlıdoğ, M. (2015). Internet censorship in Turkey. Internet Policy Review, 4(2). doi:10.14763/2015.2.366

Abdi, J., & Deane, J. (2008). The Kenyan 2007 elections and their aftermath: The role of media and communication. BBC World Service Trust. BBC World Service Trust.

Abiye, T. M. (2011, December 7). The journalist as terrorist: An Ethiopian story. Retrieved October 2, 2017, from Open Democracy: https://www.opendemocracy.net/abiye-teklemariam-megenta/journalist-as-terrorist-ethiopian-story

Allo, A. (2017). Protests, terrorism, and development: On Ethiopia’s perpetual state of emergency. Yale Human Rights and Development Journal, 19(1), 133–177. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yhrdlj/vol19/iss1/4/

Arriola, L. R., & Lyons, T. (2016). Ethipoia: The 100% election. Journal of Democracy, 27(1), 76–88. doi:10.1353/jod.2016.0011

Bach, D. C. (2011). Patrimonialism and neopatrimonialism: Comparative trajectories and readings. Commonwealth and Comparative Politics, 49(3), 275-295. doi:10.1080/14662043.2011.582731

Bach, J.-N. (2011). Abyotawi democracy: neither revolutionary nor democratic, a critical review of EPRDF’s conception of revolutionary democracy in post-1991 Ethiopia. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 5(4), 641–663. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2011.642522

Baron, D. (2009). A better pencil: Readers, writers, and the digital revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1017/s0047404511000832

Bélair, J. (2016). Ethnic federalism and conflicts in Ethiopia. Canadian Journal of African Studies, 50(2), 295–301. doi:10.1080/00083968.2015.1124580

Bergson, H. (1998). Creative evolution. New York: Dover Publications.

Bigo, D. (2000). When two become one: Internal and external securitisations in Europe. In M. Kelstrup & M. Williams (Eds.), International Relations Theory and the Politics of European Integration: Power, Security and Community (pp. 171–204). London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203187807-8

Birkland, T. (2004). “The world changed today”: Agenda‐setting and policy change in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks. Review of Policy Research, 21(2), 179–200. doi:10.1111/j.1541-1338.2004.00068.x

Bratton, M., & Van de Walle, N. (1994). Neopatrimonial regimes and political transitions in Africa. World Politics, 46(4), 453–489. doi:10.2307/2950715

Brownlie, I. (2004). Principles of public international law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burke, J. (2018, July 8). “These changes are unprecedented”: how Abiy is upending Ethiopian politics. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jul/08/abiy-ahmed-upending-ethiopian-politics

Castells, M. (2012). Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the internet age (1st ed.). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Clapham, C. (1985). Third world politics. London: Helm.

Clapham, C. (2009). Post-war Ethiopia: The trajectories of crisis. Review of African Political Economy, 36(120), 181–192. doi:10.1080/03056240903064953

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). (2012, August 3). Ethiopian appeals court reduces sentence of Reeyot Alemu. Retrieved December 5, 2018, from https://cpj.org/2012/08/ethiopian-appeals-court-reduces-sentence-of-reeyot.php

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). (2017). Journalists not terrorists: In Cameroon, anti-terror legislation is used to silence critics and suppress dissent (Special Report). New York: Committee to Protect Journalists. Retrieved from https://cpj.org/reports/Cameroon-English-Web.pdf

Conger, S., Pratt, J. H., & Loch, K. D. (2013). Personal information privacy and emerging technologies. Information Systems Journal, 23(5), 401–417. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2575.2012.00402.x

Cowen, T. (2009). Create your own economy: The path to prosperity in a disordered world. New York: Dutton.

Croucher, S. (2018). Globalization and belonging: The politics of identity in a changing world (2nd ed.). Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Currier, C., & Marquis-Boire, M. (2015, July 7). The Intercept. Retrieved March 14, 2016 https://theintercept.com/2015/07/07/leaked-documents-confirm-hacking-team-sells-spyware-repressive-countries/

Daniels, R., Macklem, P, & Roach, K. (2002). The security of freedom: Essays on Canada's Anti-Terrorism Bill. Toronto: University of Totonto Press. doi:10.3138/9781442682337-fm

Davies, S. (2008). The political economy of land tenure in Ethiopia (PhD Thesis, University of St. Andrews). Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10023/580

De Frias, A. M. S., Samuel-Azran, K., & White, N. (Eds.). (2012). Counter-terrorism: International law and practice (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Di Nunzio, M. (2014). ‘Do not cross the red line’: The 2010 general elections, dissent, and political mobilization in urban Ethiopia. African Affairs, 113(452), 409–130. doi:10.1093/afraf/adu029

Dirbaba, B., & O’Donnell, P. (2012). The double talk of manipulative liberalism in Ethiopia: An example of new strategies of media repression. African Communication Research, 5(3), 283–312.

Dripps, D. (2013). “Dearest property”: Digital evidence and the history of private “papers” as special objects of search and seizure. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 103(1), 49–109. Retrieved from https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol103/iss1/2/

Eisenstadt, S. N. (1973). Traditional patrimonialism and modern neopatrimonialism. London: Sage Publications.

Erdmann, G., & Engel, U. (2007). Neopatrimonialism reconsidered: Critical review and elaboration of an elusive concept. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 45(1), 95–119. doi:10.1080/14662040601135813

Fana, G. (2014). Securitisation of development in Ethiopia: the discourse and politics of developmentalism. Review of African Political Economy, 41(1), S64–S74. doi:10.1080/03056244.2014.976191

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE). (1995). Proclamation of the Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Federal Negarit Gazeta. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.42063

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE). (2009). A Proclamation on anti-terrorism. Federal Negarit Gazeta. Retrieved from http://www.refworld.org/docid/4ba799d32.html

Fenton, N. (2016). The internet of radical politics and social change. In J. Curran, N. Fenton, & D. Freedman (Eds.), Misunderstanding the Internet (pp. 173–202). London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315695624-6

Freedman, L. (1998). International security: Changing targets. Foreign Policy, 110, 48–64. doi:10.2307/1149276

Fuchs, C., & Trottier, D. (2017). Internet surveillance after Snowden: A critical empirical study of computer experts’ attitudes on commercial and state surveillance of the internet and social media post-Edward Snowden. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, 15(4), 412–444. doi:10.1108/jices-01-2016-0004

Gashaw, S. (1993). Nationalism and ethnic conflict in Ethiopia. In C. Young (Ed.), The rising tide of cultural pluralism: The nation state at bay? (pp. 138-157). Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.

Gerschewski, J., & Dukalskis, A. (2018). How the internet can reinforce authoritarian regimes: The case of North Korea. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, 19, 12–19. doi:10.1353/gia.2018.0002

Gasteyger, C. (1999). Old and new dimensions of international security. In K. Spillmann & A. Wenger (Eds.), Towards the 21st Century: Trends in Post-Cold War International Security Policy (Vol. 4, pp. 69–108). Bern: Peter Lang.

Grigoryan, A. H. (2013). A model for anocracy. Journal of Income Distribution, 22(1), 3–24. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/a/jid/journl/y2013v22i1p3-24.html Available at https://newsroom.aua.am/files/2013/12/Model-for-Anocracy.pdf

Grinberg, D. (2017). Chilling developments: Digital access, surveillance, and the authoritarian dilemma in Ethiopia. Surveillance & Society, 15(3–4), 432–438. doi:10.24908/ss.v15i3/4.6623

Gudina, M. (2007). Ethnicity, democratisation and decentralization in Ethiopia: The case of Oromia. Eastern Africa Social Science Research Review, 23 (1), 81-106. doi:10.1353/eas.2007.0000

Gudina, M. (2011). Elections and democratization in Ethiopia, 1991–2010. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 5(4), 664–680. doi:10.1080/17531055.2011.642524

Habtu, A. (2003). Ethnic federalism in Ethiopia: Background, present conditions and future prospects. Second EAF International Symposium on Contemporary Development Issues in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Hamzawy, A. (2017). Legislating authoritarianism: Egypt’s new era of repression (Paper). Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/2017/03/16/legislating-authoritarianism-egypt-s-new-era-of-repression-pub-68285

Heinlein, P. (2012, January 8). Ethiopian politicians on trial for terrorism. Voice of America. Retrieved from https://www.voanews.com/a/ethiopian-politicians-on-trial-for-terrorism-136960163/159430.html

Hellmeier, S. (2016). The dictator’s digital toolkit: Explaining variation in internet filtering in authoritarian regimes. Politics & Policy, 44(6), 1158–1191. doi:10.1111/polp.12189

Horne, F., & Wong, C. (2014). “They know everything we do”: Telecom and internet surveillance in Ethiopia (Report). New York: Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/03/25/they-know-everything-we-do/telecom-and-internet-surveillance-ethiopia

Human Rights Watch. (2013a). Ethiopia: Terrorism law decimates media. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/05/03/ethiopia-terrorism-law-decimates-media

Human Rights Watch. (2013b). “They want a confession” Torture and ill-treatment in Ethiopia’s Maekelawi police station. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/report/2013/10/17/they-want-confession/torture-and-ill-treatment-ethiopias-maekelawi-police-station

International Telecommunication Union (ITU). (2018a). Country ICT data: Percentage of individuals using the internet. Retrieved from https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/stat/default.aspx

International Telecommunication Union (ITU). (2018b). Ethio Telecom. Retrieved October 1, 2018, from https://telecomworld.itu.int/exhibitor-sponsor-list/ethio-telecom/

Jacob, F. (2016). The role of m-pesa in Kenya’s economic and political development. In M. M. Koster, M. M. Kithinji, & J. Rotich (Eds.), Kenya after 50. African histories and modernities. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137574633_6

Kalathil, S., & Boas, T. (2003). Open networks, closed regimes: The impact of the internet on authoritarian rule. Washington D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. doi:10.5210/fm.v8i1.1025

Karatzogianni, A., & Robinson, A. (2017). Schizorevolutions versus microfascisms: The fear of anarchy in state securitisation. Journal of International Political Theory, 13(3), 282–295. doi:10.1177/1755088217718570

Kelsall, T. (2013). Business, politics, and the state in Africa: Challenging the orthodoxies on growth and transformation. London: Zed Books.

Kerr, J. A. (2018). Information, security, and authoritarian stability: Internet policy diffusion and coordination in the former Soviet region. International Journal of Communication, 12, 3814–3834. Retrieved from https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/8542

Kidane, M. (2001). Ethiopia’s ethnic-Based federalism: 10 years after. African Issues, 29(1–2), 20–25. 10.2307/1167105

Kibret, Z. (2017). The terrorism of ‘counterterrorism’: The use and abuse of anti-terrorism law, the case of Ethiopia. European Scientific Journal, 13(13), 504-539. doi:10.19044/esj.2017.v13n13p504

Kotz, D., Gunter, C. A., Kumar, S., & Weiner, J. P. (2016). Privacy and security in mobile health: A research agenda. Computer, 49(6), 22–30. 10.1109/MC.2016.185

Loriaux, M. (1999). The French development state as a myth and moral ambition. In M. Woo-Cumings (Ed.), The developmental state (pp. 235–275). New York: Cornell University Press.

Lyons, T. (2016). From victorious rebels to strong authoritarian parties: prospects for post-war democratization. Democratization, 23(6), 1026–1041. doi:10.1080/13510347.2016.1168404

Maasho, A. (2018, May 30). Ethiopian government and opposition start talks on amending anti-terrorism law. Reuters. Retrieved from https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-ethiopia-politics/ethiopian-government-and-opposition-start-talks-on-amending-anti-terrorism-law-idUKKCN1IV1RL

MacKinnon, R. (2011). Liberation technology: China’s “networked authoritarianism.” Journal of Democracy, 22(2), 32–46. doi:10.1353/jod.2011.0033

Marquis-Boire, M., Marczak, B., Guarnieri, C., & Scott-Railton, J. (2013, March 13). You only click twice: FinFisher’s global proliferation. (U. o. The Citizen Lab, Producer) Retrieved July 8, 2016, from The Citizen Lab: https://citizenlab.org/2013/03/you-only-click-twice-finfishers-global-proliferation-2/

Matfess, H. (2015). Rwanda and Ethiopia: Developmental authoritarianism and the new politics of African strong men. African Studies Review, 58(2), 181–204. doi:10.1017/asr.2015.43

Mehretu, A. (2012). Ethnic federalism and its potential to dismember the Ethiopian state. Progress in Development Studies, 12(2–3), 113–133. doi:10.1177/146499341101200303

Mkandawire, T. (2001). Thinking about developmental states in Africa. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 25(3), 289–314. doi:10.1093/cje/25.3.289

Morozov, E. (2013, March 23). Imprisoned by innovation. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/24/opinion/sunday/morozov-imprisoned-by-innovation.html?_r=0

Nakashima, E. (2016, February 17). Apple vows to resist FBI demand to crack iPhone linked to San Bernardino attacks. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/us-wants-apple-to-help-unlock-iphone-used-by-san-bernardino-shooter/2016/02/16/69b903ee-d4d9-11e5-9823-02b905009f99_story.html

Nunes Lopes Espiñeira Lemos, A., & Pasquali Kurtz, L. (2018). Sovereignty over personal data in Brazil: State jurisdiction facing denial of access to users’ data by online platform Whatsapp. Presented at the GigaNet: Global Internet Governance Academic Network, Annual Symposium 2017, SSRN. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3107293

Pen International. (2011, September 23). Ethiopia: Two more journalists arrested under antiterrorism legislation; fears of torture. Pen International. Retrieved February 21, 2019, from https://pen-international.org/news/ethiopia-two-more-journalists-arrested-under-antiterrorism-legislation-fears-of-torture

Pohle, J., & Van Audenhove, L. (2017). Post-Snowden internet policy: Between public outrage, resistance and policy change. Media and Communication, 5(1), 1–6. doi:10.17645/mac.v5i1.932

Powell, J. D. (1970). Peasant societies and clientelist politics. American Political Science Review, 64(2), 411–425. doi:10.2307/1953841

Rice, X., & Goldenberg, S. (2007, January 13). How US forged an Alliance with Ethiopia over Invasion . The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/jan/13/alqaida.usa

Roach, K. (2012). The criminal law and its less restrained alternatives. In V. V. Ramraj, M. Hor, K. Roach, & G. Williams (Eds.), Global anti-terrorism law and policy (pp. 91-121). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139043793.007

Roach, K. (2015). Comparative counter-terrorism law comes of age. In K. Roach (Ed.), Comparative counter terrorism law (pp. 1-48). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781107298002.001

Roach, K., Hor, M., Ramraj, V. V., & Williams, G. (2012). Introduction. In V. Ramraj, M. Hor, K. Roach, & G. Williams (Eds.), Global anti-terrorism law and policy (2nd ed., pp. 1-16). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/cbo9781139043793.001

Sanger, D., & Schmitt, E. (2015, February 1). Hackers use old lure on web to help syrian government. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/02/world/middleeast/hackers-use-old-web-lure-to-aid-assad.html

Schneiderman, D., & Cossman, B. (2002). Political association and the Anti-Terrorism Bill. In R. J. Daniels, Macklem, P, & K. Roach (Eds.), The security of freedom: Essays on Canada's Anti-Terrorism Bill (pp. 173-194). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. doi:10.3138/9781442682337-012

Shirky, C. (2008). Here comes everybody: The power of organizing without organizations. New York: Penguin Press.

Sekyere, P., & Asare, B. (2016). An examination of Ethiopia's anti-terrorism proclamation on fundamental human rights. European Scientific Journal, 12(1), 351-371. doi:10.19044/esj.2016.v12n1p351

Setty, S. N. (2012). The United States. In K. Roach (Ed.), Comparative counter-terrorism law (pp. 49-77). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781107298002.002

Sreberny, A. (2014). Violence against women journalists. In A. V. Montiel (Ed.), Media and gender: a scholarly agenda for the Global Alliance on Media and Gender (pp. 35–43). Paris: UNESCO.

Sutherland, E. (2018, June 22). Digital privacy in Africa: Cybersecurity, data protection & surveillance. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3201310

Tronvoll, K. (2008). Human rights violations in federal Ethiopia: When ethnic identity is a political stigma. International Journal on Minority and Group Rights, 15(1), 49–79. doi:10.1163/138548708x272528

Turse, N. (2017, September 13). How the NSA built a secret surveillance network for Ethiopia. The Intercept. Retrieved October 14, 2017: https://theintercept.com/2017/09/13/nsa-ethiopia-surveillance-human-rights/

van de Walle, N. (1994). Neopatrimonialism and democracy in Africa: with an illustration from Cameroon. In J. Widner (Ed.), Economic change and political liberalization in sub-Saharan Africa. (pp. 129-157). Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Vestal, T. M. (1999). Ethiopia: A post-Cold War African state. Westport: Praeger.

Villasenor, J. (2011). Recording everything: Digital storage as an enabler of authoritarian governments. Washington, DC: Brookings Institute.

Weingrod, A. (1968). Patrons, patronage, and political parties. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 10(4), 377–400. doi:10.1017/s0010417500005004

Weis, T. (2016). Vanguard capitalism: party, state, and market in the EPRDF’s Ethiopia. (Phd Thesis, University of Oxford). Retrieved from https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:c4c9ae33-0b5d-4fd6-b3f5-d02d5d2c7e38

Workneh, T. (2015). Digital cleansing? A look into state-sponsored policing of Ethiopian networked communities. African Journalism Studies, 36(4), 102-124. doi:10.1080/23743670.2015.1119493

Workneh, T. (2018). State monopoly of telecommunications in Ethiopia: origins, debates, and the way forward. Review of African Political Economy. doi:10.1080/03056244.2018.1531390

Yang, F. (2014). Rethinking China’s internet censorship: The practice of recoding and the politics of visibility. New Media & Society, 18(7), 1364–1381. doi:10.1177/1461444814555951

Footnotes

1. See Bach (2011) for a discussion on EPRDF’s theory and practice of abyotawi dimokrasi.

2. EPRDF’s political discourse of “developmentalism” is rooted in the theory of the developmental state. The developmental state, according to Loriaux (1999), is “an embodiment of a normative or moral ambition to use the interventionist power of the state to guide investment in a way that promotes a certain solidaristic vision of national economy” (p. 24). The role of the elite developmental state model, Mkandawire (2001) contends, is “to establish an ‘ideological hegemony,’ so that its development project becomes, in a Gramscian sense, a ‘hegemonic’ project to which key actors in the nation adhere voluntarily” (p. 290). While EPRDF maintained the notion of development trumps all other priorities, critics argue that the party’s adoption of the developmental state theory into a political program is nothing more than an attempt to institutionalize rent seeking interests of the ruling elite (for example, see Berhanu, 2013).

3. For example, Kibret (2017) has identified more than 120 cases under which the Federal Public Prosecutor has charged nearly one thousand individuals by citing the provisions of the EATP. Most of these individuals have been charged for alleged affiliation with domestic rebel groups proscribed by the Ethiopian parliament as “terrorist organizations” in June 2011. These rebel groups include Ginbot 7 for Justice, Freedom and Democracy (Ginbot 7), Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), Oromo Liberation Front (OLF). From the 985 individuals prosecuted under the EATP between September 2011 and March 2017, a third of all the charges involve civilians who have “nothing to do with either terrorism or the rebel groups” (p. 524).

4. An anocracy represents a political system which is neither fully democratic nor fully autocratic, often being vulnerable to political instability. See Grigoryan (2013).

5. See Nunes Lopes Espiñeira Lemos & Pasquali, and Kurtz (2018), Sutherland (2018) on global information extraction practices emanating from state-sponsored surveillance. In the Ethiopian context, information extraction is usually related to seizure of a digital apparatus by government officials to obtain information although other forms of the practice including surveillance are also common. For example, see Horne & Wong (2014).

6. For example, in Soliana Shimeles et al. v the Federal Public Prosecutor involving ten bloggers and journalists as defendants, the Federal Public Prosecutor charged the defendants under Article 3 of the Anti-Terrorism proclamation accusing them of “serious risk to the safety or health of the public or section of the public” and “serious damage to property”. The prosecutor presented, as part of its evidence, several pages of transcripts of phone conversations belonging to the defendants.

7. See note 4 for more on Ginbot 7

8. Article 14(4) of EATP states: “The National Intelligence and Security Services or the Police may gather information by surveillance in order to prevent and control acts of terrorism” (Federal Negarit Gazeta, 2009, p. 4834).

9. For example, the EATP was used to convict prominent Ethiopian media practitioners including Eskinder Nega, a journalist and blogger who received the 2012 PEN Freedom to Write Award, to serve a sentence of 18 years in prison (Dirbaba & O’Donnell, 2012). Another convicted journalist is 2012 Hellman-Hammett Award winner Woubshet Taye, who was sentenced to serve a 14-year sentence under the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation (Heinlein, 2012). Other journalists and media practitioners who faced charges under the anti-terrorism proclamation include Mastewal Birhanu, Yusuf Getachew and Solomon Kebede (Human Rights Watch, 2013a).

10. Article 29 (2) of the Ethiopian Constitution states: “Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression without interference. This right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through other media of his choice” (FDRE, 1995, p. 9)

11. Zone 9 bloggers founding member, personal correspondence, 15 October 2017.

12. See Kibret (2017) for a complete list of cases involving the Ethiopian Anti-Terrorism Proclamation.

13. Ethiopia’s internet penetration--though improving--lags behind several other African countries. For details, see ITU, 2018a.

14. In July 2018, the Ethiopian House of Peoples’ Representatives, upon the Cabinet of Ministers’ recommendation, removed Ginbot 7, OLF, and ONLF from its terror list. In January 2019, the FDRE government announced it pardoned 13,000 accused of treason or terrorism.

Add new comment